Science & SkepticismTrawling For Trash

Paddle Surfers Helping To Assess Nearshore Microplastic Pollution

“Microplastics have invaded every part of the planet today, from the most remote place inland to the sea surface and the deep sea. But our understanding of the properties, behaviour and distribution of microplastics in the marine environment is still incomplete,” says Anna Sanchez-Vidal, associate professor at University of Barcelona (UB) and corresponding author for a pioneering scientific study published last month on the potentials of using paddle surfing to assess microplastic pollution in nearshore areas.

She points out that “while many studies have investigated floating microplastics in surface waters offshore, there is almost no information on floating microplastics in surface waters at less than a few hundred meters from the coastline,” due to the shallow depths and presence of swimmers, which impede research vessels to come close to the shore. However, she also stresses that it is in this particular area “where the largest plastic mass flux is suspected to occur – more than 80% of the plastic in the sea comes from land-based sources.”

With that in mind, Sanchez-Vidal, together with a group of researchers at University of Barcelona, volunteers, and the help of Surfrider Foundation Europe, set off to sample two nearshore areas off Barcelona, in the western Mediterranean. They have done so by equipping volunteer stand-up paddle surfers with a newly designed mechanism – aptly named the ‘paddle trawl’ – and monitoring the surfers’ location with the Wikiloc Outdoor app while they paddled along the coast for 30 minutes to an hour.

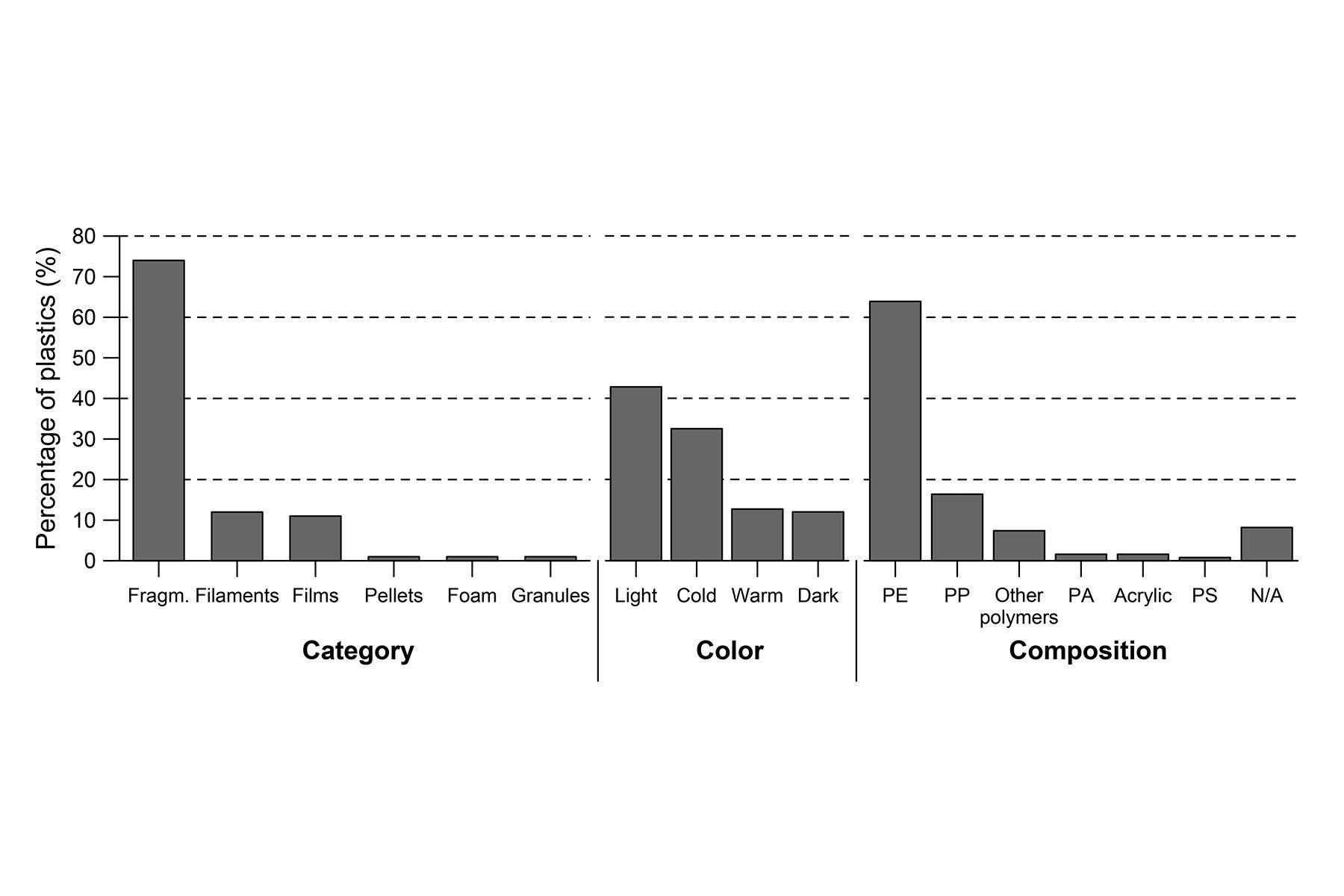

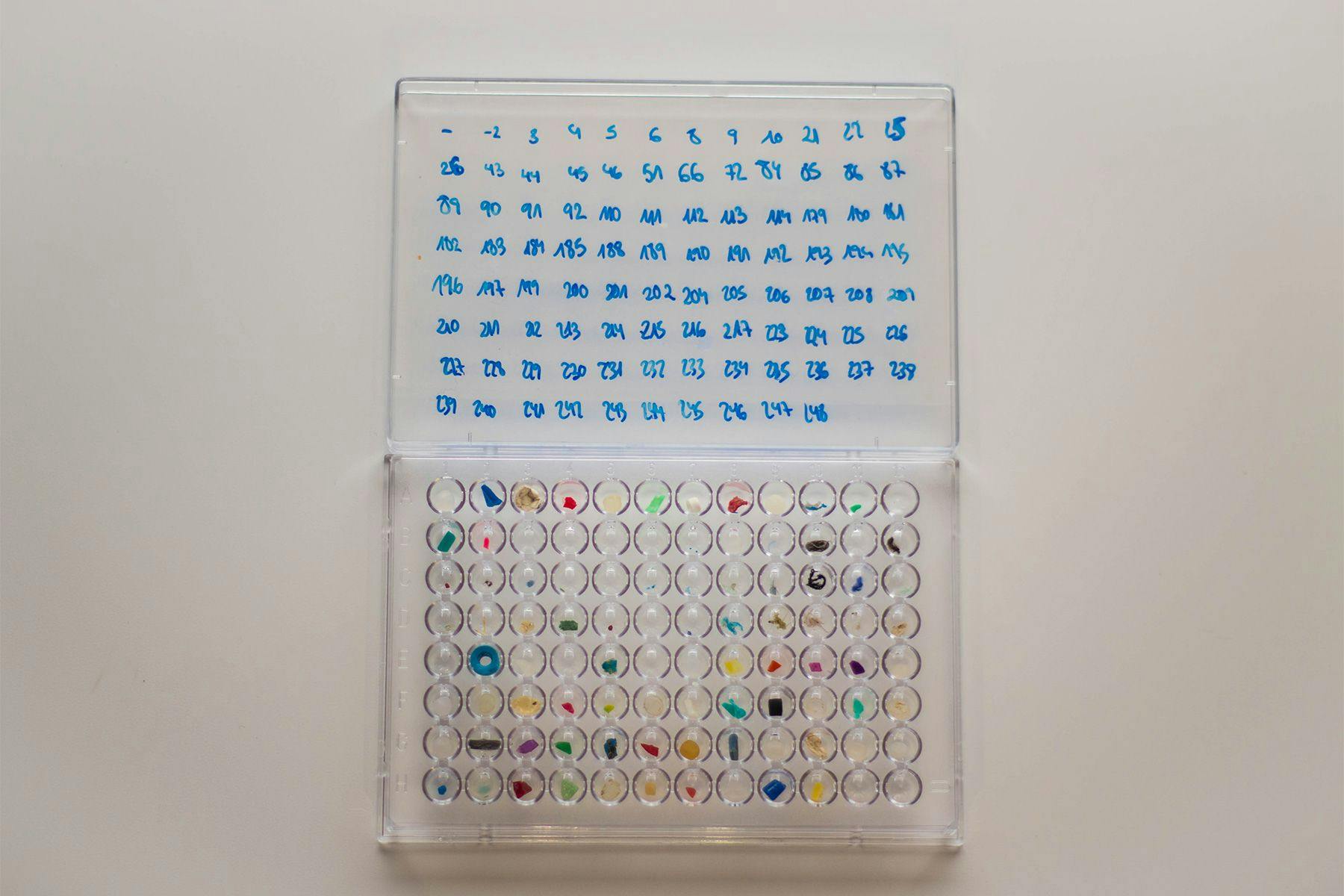

Samples were then transferred to glass containers and taken to the university research lab for analysis, where they were classified by size (microplastics [0.33 –5 mm], mesoplastics [5 –25 mm], and macroplastics [>25 mm]); nature and shape (fragments, filaments, films, pellets, foam, and granules); colour (dark [e.g. black and grey], light [e.g. white and yellow], cold [e.g. green and blue], and warm [e.g. red and orange]); and polymer composition.

Results showed that the abundance of microplastics collected amounted to 84%, whereas mesoplastics only 15%, and macroplastics a negligible 1%. When comparing the data gathered with those of studies conducted offshore, however, the total plastic abundance was similar to those found offshore in the Mediterranean Sea which, as Sanchez-Vidal remarks, “has been proposed as the sixth great accumulation zone for marine litter, together with the main five oceanic gyres.” That being said, they also “found that plastic items are relatively larger in the nearshore, which suggests that this area is likely to produce and export microplastics towards offshore waters.”

Beyond the data, this was an experiment on citizen science, and when it comes to such kinds of projects, education is as important as action. During this particular Barcelona study, the team worked with the assistance of the Barcelona Chapter of Surfrider Foundation Europe to recruit and train volunteers. The results were then shared by researchers and Marine Science undergraduates at the 2019 Posidonia Green Festival, held in Barcelona.

“Surfrider volunteers are typically motivated and publicity was maximised through social media. Social media kept the Surfrider Europe’s citizen science community engaged and, in the outcome phase, feedback to citizen scientists was provided through collaboration with scientists and marine science students at the University of Barcelona,” says Sanchez-Vidal. She adds that “the engagement between volunteers, an NGO, undergraduate students and scientists provided a scientifically rigorous, incredibly valuable and publishable data set that contributed to fill the gap in knowledge of the abundance and characteristics of floating microplastics in the nearshore, that would be extremely difficult for researchers alone to collect.”

But the publication of the paper wasn’t the end of the study. Having collected almost one year’s worth of scientific samples varying in abundance and characteristics (polymer, shape, colour, origin), Sanchez-Vidal and her team continue to sample beaches around Barcelona every week.

“We have been sampling before and after the occurrence of a major storm that hit the Catalan coast this last January. The storm – called Gloria – triggered maximum wave heights of 14 m, large floods and strong erosion on land, and washed ashore huge amounts of plastic waste (perfectly preserved plastic litter 50 years old was found in beaches, referred to as “Gaia’s revenge”),” she says, adding that “results will provide important information on microplastic transport and accumulation when this land-to-sea transfer of plastic litter (in both directions!) occurs as its maximum intensity.”

Although the project is currently run in Barcelona, Sanchez-Vidal says that, for those who wish to participate somehow, “it’s just about building a trawl and getting in touch with any university or research centre nearby working on microplastics. They will coordinate sampling and provide instructions on how to proceed to gather scientifically reliable data.”

In essence, the results prove that paddle surfers can effectively collect microplastic samples in nearshore areas for scientific analysis when equipped with the proposed paddle trawl. But Sanchez-Vidal is confident there is much more to it: “This citizen science initiative overcomes the high costs of oceanographic sampling, and at the same time allows enhanced spatial and temporal resolution of plastic pollution monitoring. This cooperation provides extraordinary benefits for science, citizen scientists, and society in general!”

The author and Surf Simply would like to thank Anna Sanchez-Vidal of University Barcelona and Vanessa Sarah Salvo, Scientific Director at Posidonia Green Project for their assistance with the article and providing the images.