Surf ContestsRisk vs. Reward: The Potential Price of Pipe

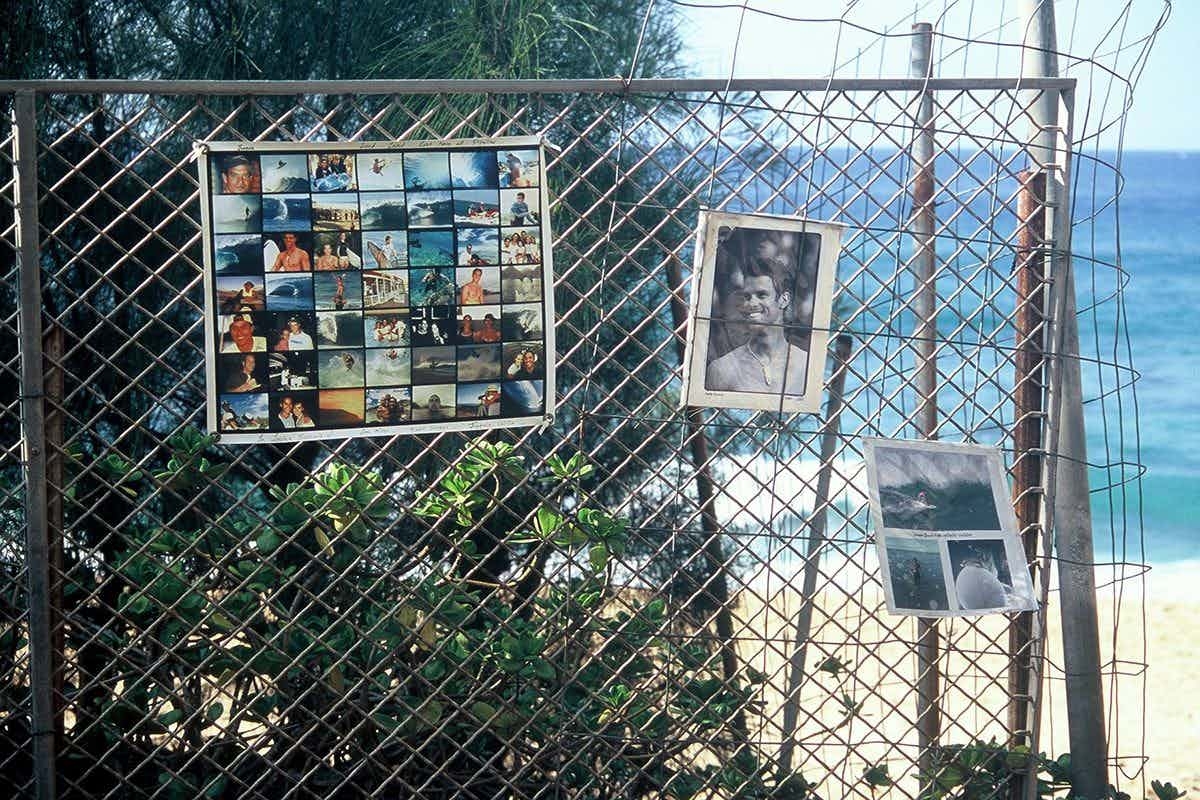

On the western boundary fence of Ehukai Beach Park, right where you step onto the sand and turn left to walk the short distance down the beach from the parking lot towards Pipeline, there used to be, and probably still are, a bunch of photographs attached to the wire mesh of the fence.

Much like flowers left on the roadside at the site of a fatal car accident, these photos serve as a memorial to surfers who have lost their lives at surfing’s most famous break. It’s a heavy and sobering reminder. Pipeline has had a terrifying reputation right from the get-go, with many surfers being introduced to the wave by Bruce Brown’s 1966 classic The Endless Summer just a few years after Brown first documented the wave being surfed successfully by Phil Edwards in December 1961 (for his film Surfing Hollow Days). In his commentary for The Endless Summer, Brown tells the audience that Pipeline is a break “so dangerous it almost defies description”, and goes on to describe the coral seafloor whilst showing wipeout after horrible wipeout.

“At most places when someone gets wiped out, everyone watching on the beach laughs. No one laughs at the Pipeline, they wait and see if you come up again.”

Bruce Brown, The Endless Summer

Just a year after that film was released, the first fatality occurred as a result of a wipeout at Pipeline; former Peruvian national champion Joaquin Miro Quesada hit the reef and broke his neck, passing away several hours later. Since then, with all eyes on Pipeline as it rose to prominence as surfing’s most well-known and recognisable wave, the break has become a proving ground. However, whilst there are plenty of surf spots the world over that have a dark and dangerous side to them, few are as high profile as Pipeline and fewer still can make, break or define careers thanks to the massed ranks of photographers in the water and on the beach when it gets over eight foot. Large numbers of professional surfers and local Pipe specialists sit in line for waves here, alongside visiting amateur and aspiring professional surfers who want to pin a Pipeline badge to their lapel, and this can often lead to a tense line-up and poor decision making on the part of some surfers. Regardless, all look out for one another though. Some surfers perhaps make bad calls and go on waves that they should’ve let go by, whereas others are simply unlucky; when a wave that large and powerful breaks in just six to ten feet of water the chances of hitting your head on either the bottom during a wipeout become very real. This winter alone has seen a number of high profile head injuries at Pipe, Backdoor and their western neighbor Off The Wall, including Evan Geiselman’s dramatic rescue by Andre Botha, Mikala Jones taking his fins to his face (which required 21 stitches to make right), and Owen Wright withdrawing from the Billabong Pipe Masters after sustaining a severe concussion and minor bleeding on the brain when he hit his head during a free-surf. Fortunately Evan, Mikala and Owen have all lived to tell the tale, however their high profile injuries highlights the risks that surfers take at such breaks and why we term them “waves of consequence”.

“It’s no joke out there. It’s a very, very, dangerous spot”

Bruce Irons

To cite Matt Warshaw in The Encyclopedia of Surfing, it is estimated that a surfer dies at Pipeline every other year, which is not a statistic to be taken lightly. With Round 3 of this year’s Billabong Pipe Masters due to get underway again today and with the Men’s World Title still up for grabs, the balance of risk and reward is something that each competitor (and the title contenders in particular) has to settle upon for themselves every time a set wave looms up on the horizon. World titles aside though, the reward of just getting a good wave at Pipe is enormous, and one that many surfers will never get the chance to enjoy.