SurfboardsThe History of Surfboard Design: Bob McTavish and The Vee Bottom (aka Plastic Machine)

The vee-bottom contour was a pivotal feature for the more turn-oriented style of surfing that emerged in the mid-sixties. Consisting initially of two angled panels that met in the centre and ran longitudinally through the rear third of the board, the design prompted the creation of a surfboard model of the same name by Australian surfer-shaper Bob McTavish. After assisting world champion Nat Young in designing Magic Sam, McTavish probed even further into the performance of his friend and fellow boardmaker, Californian kneeboarder George Greenough. In March 1967, he implemented the vee-shaped bottom design on his first Plastic Machine – a 9’ x 23” model that showcased an unprecedented range of manoeuvrability and, later being refined to shorter lengths, kindled the shortboard revolution.

The Historical Context

The wildcat “total involvement” movement of the 60s prompted surfer-cum-shapers to branch away from nose-riding, sparking a frenzy of experimentation in the shaping bay. It was in 1964, in Australia, that this direction seeking began to find its True North. After sojourning in New South Wales, Californian kneeboarder George Greenough, who had been carving up and down the wave face on a 4’10” low-volume kneeboard, fed local visionaries Bob McTavish and Nat Young with an eidetic example of what could be accomplished in terms of wave-riding, whilst also emphasizing the limitations of their over-9-footers. Inspired by the encounter, the Aussies resolved to find ways to reproduce Greenough’s performance whilst stand-up surfing. This eventually culminated in Nat Young’s 1966 world title run when, using his brand new board, “Magic” Sam, he demonstrated the sort of radical surfing aspired to in “total involvement”. This example, in turn, provided the empirical push for board designers to commit to shorter, lighter, and more versatile equipment.

Aiming to dig his foot even deeper into the newfound micro cosmos of manoeuvrability, and taking advantage of his position as a shaper at Keyo Surfboards, McTavish developed the original vee-bottom surfboard in March of 1967, nicknaming it the Plastic Machine. He put a 9’0” big-wave version of the new design to the test later that year in Hawaii; though the board didn’t perform well in big surf, a six- to eight-foot session at Honolua Bay (captured in Paul Witzig’s 1968 The Hot Generation), revealed the potential behind his design and disseminated interest across the surfing public at large. This series of events cleared the path for the transition from longboarding to shortboarding, coalescing in the shortboard revolution. McTavish put out several vee-bottoms over the coming months, gradually making them lighter and smaller. The Plastic Machine remained the go-to surfboard model through 1968 alongside Dick Brewer’s mini-gun, in a kind of design limbo that lasted until 1969, when boardmakers across the globe began experimenting with design features at will and creating new models altogether, thus pushing vee-bottoms to the background.

Why Was This Development Necessary?

Along with Magic Sam and the Fish, the vee-bottom surfboard was a purposeful move away from nose-riding as the primary measure of high performance, and a by-product of the “total involvement” approach to surfing – a movement which essentially aimed to put manoeuvrability as the prima concept of high-performance. Innovative surfers wanted to eschew straight-line surfing and have more control over the board’s direction so they could choose their own track, explore all of the wave’s face, and make the most of power pockets. But as far as boardmakers could fathom, the dichotomy between nose-riding and radical manoeuvring was an either-or situation: you chose one at the expense of the other. Translating to board design, the heftiness of average surfboards (which were around 9’6” long and weighed more than 20 pounds) presented an impediment toward the responsiveness sought by surfers. And though the fundamental motifs for their inception were shared, McTavish’s vee-bottom addressed something neither Lis’ Fish nor Young’s Magic Sam had explored thoroughly: foot positioning. By focusing on the rail-to-rail transition, surfers needn’t walk all the way to the tail to facilitate an abrupt change in direction, and could now turn more easily and sharply, whilst recovering from turns more quickly by reaching power positions that avoid loss of speed.

Who Was Involved?

Once hailed by Surfing Life magazine as the “Most Influential Shaper of All Time,” Australian Bob McTavish (b. 1944) consistently drew on his enthusiastic character and dynamic, all-encompassing surfing style to push wave-riding and surfboard design to the next level. Raised in Queensland, McTavish rode his first waves on hollow plywood paddleboards at age 12. He dropped out of high school at 15 and, moving to Sydney at 17, began shaping under the wings of renowned board makers such as Joe Larkin of Larkin Surfboards and Danny Keyo of Keyo Surfboards. By the mid-60s, McTavish joined forces with fellow-countryman Nat Young and Californian George Greenough to create the “total involvement” school of surfing – a movement which informed most of his work in the years to come, including the birth of the vee-bottom surfboard.

Despite having three Queensland state titles (1964 to 1966) and two remarkable performances at the Australian National Titles (3rd in 1965 and 2nd in 1966) under his belt, McTavish, along with his nine-foot Keyo Plastic Machine, slid under the international spotlight during the 1967 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational. After a mediocre performance in the competition at Sunset Beach, he took his vee-bottom out to Honolulu Bay, surfing sessions whose footage appeared in the iconic surf film The Hot Generation spreading the awareness of high-performance surfing potential across global surf media.

McTavish all but vanished from the industry when he moved to the north coast of New South Wales with his family in 1970, and only reappeared in 1977 writing a series of surf magazine articles championing longboarding at a time when shortboards dominated. In 1989 he took a shot at reproducing boards used by top professional surfers in molded epoxy construction (Pro Circuit Boards), a technique that eventually caught on in the late nineties as Surftech’s Tuflite. Toward the turn of the millennium McTavish developed a range of longboards that would be licensed by manufacturing giants Global Surf Industries and SurfTech.

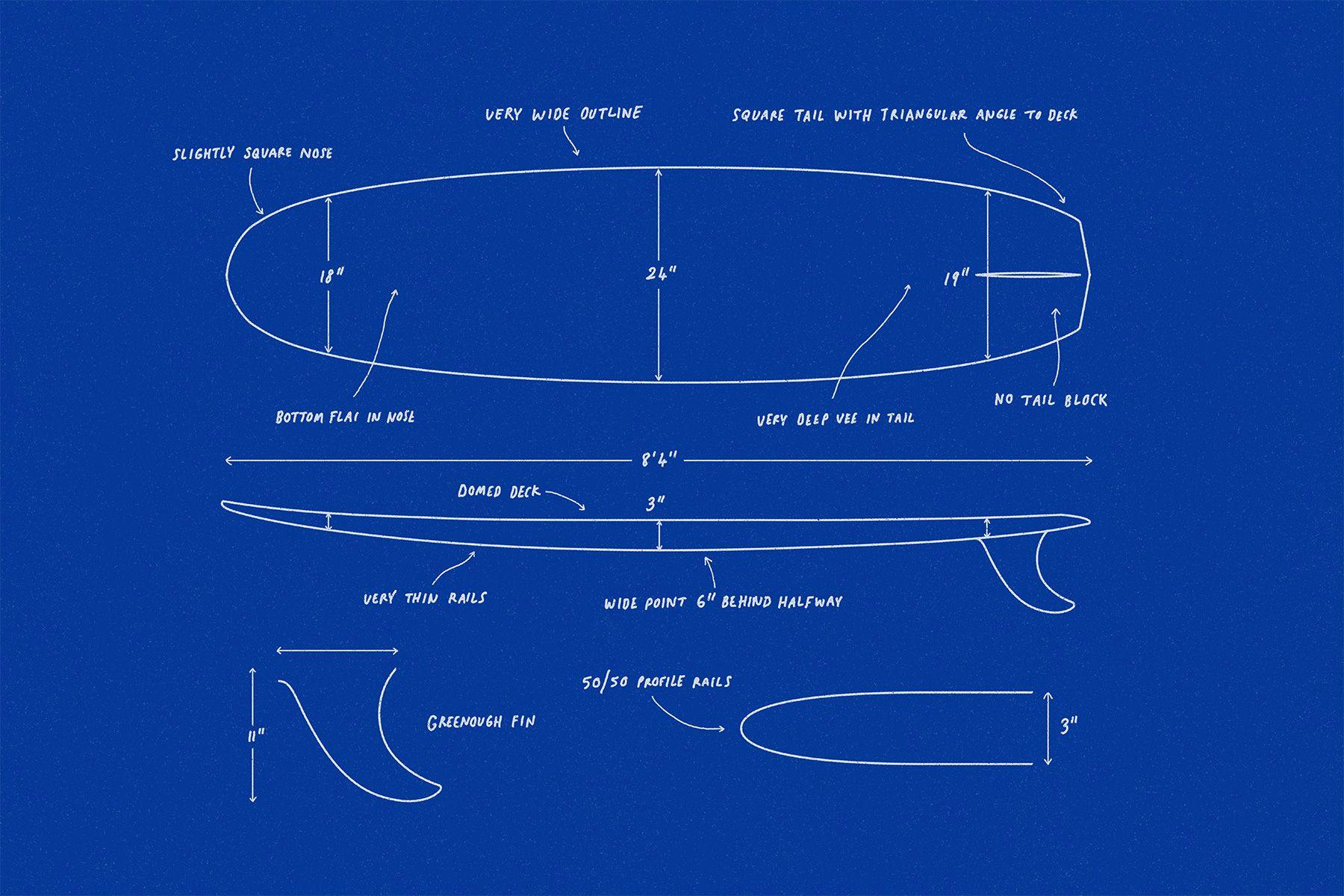

Design Details

At 9’ in length and 23” in width, the dimensions of the original Plastic Machines weren’t too disimilar from that of its predecessor Magic Sam or Velzy’s Pig (though later versions were scaled down to 7’6” and 14lb). Neither was its curved outline, or the idea of having the widest point of the outline a few inches back from the midpoint in order to reduce the surface area on the nose section and facilitate easier turning. The square shape of the tail also didn’t stray from that of its forerunners, only the width was increased by a couple of inches. Thickness-wise, the Plastic Machine retained Magic Sam’s 2 1/2”; as it did also the rounded nose and the glassed-on, high-rake fin (borrowed from Greenough’s spoons and positioned a bit closer to the back foot) whose hold during turns wasn’t compromised by drag. The rails too were the standard 50/50 egg shape. However, the bevel increased along the bottom of the board, creating a v-shape profile beginning roughly a foot forward of the fin, thus putting more surface area of the tail of the board in contact with the water when turning.

The Plastic Machine’s features differed in the more pronounced rocker; slightly more lift on the nose assisted in driving up the wave face toward snaps and re-entries. But ultimately, besides being shaped from a stringerless blank, the thing that marked the vee-bottom surfboard apart was the contour of its underside. Bearing a deep v-shape, the planning surface was bisected into two flat panels that ran through the rear third of its length from the tail until roughly a foot ahead of the fin, causing the rocker line at the stringer to be higher than at the rail. This shape caused the board to sit deeper in the water, reducing lift. It also made the board lean over with ease when pressured near the tail in heel-to-toe weight-shifts, resulting in quicker rail-to-rail transitions and, consequently, more precise drive, more response during turns, and tighter arcs. Conversely, in straight lines, vee-bottom boards moved slower than those with flat or concave bottom contours due to the increased drag of the bottom contour. Their performance was also impacted by this in more powerful waves, when the board either tipped over or would track on one rail and climb out of the water.

Refinements in the 70s introduced the “spiral vee,” essentially transferring the peak in the bisection nearer the fin whilst hollowing the panels out towards the rail with the aim of creating more bite. In the early 90s, the “reverse vee” (devised by Maurice Cole) adopted principles from concave and flat bottom contours to render a planing surface that, as the name suggests, featured an inversion in the nose entry which increased till the middle section (its apex beneath the front foot), then transformed into two subtle concave troughs, leaving the tail section flat enough to aid in stability and accelerating, particularly for front-foot-heavy surfers who benefited from extra control and easier turning ability off the back foot.

Specifications

Avg Minimum Avg Maximum Length 7’6” 9”

Width

Nose 17 1/2” Midpoint 21” 24” Tail 18” Thickness 2 1/2” 3” Weight 14lb