SurfboardsThe History of Surfboard Design: Asymmetric Surfboards

A left-field and often-overlooked design movement within the history of surfboard design, asymmetric surfboards have made a series of discrete re-appearances since the concept was first experimented with in the early sixties. They are not necessarily a defined model such as the mini-gun or the fish, more an approach to designing and shaping such models. Despite their theoretical merits, asymmetrical surfboards remain largely misunderstood and under-utilised. Over the last decade, however, with the rise of free-surfing and the growing trend for experimental designs, asymmetric boards have experienced a resurgence with the potential to not only become a highly marketable type of surfboard but also introduce a whole new approach to riding waves.

The Historical Context

The introduction of asymmetry as a deliberate design feature first happened in the early 1960s, but it didn’t gain any traction and was quickly sidelined by other developments of the era: firstly because it came across as a relatively trivial concept given the horizontal nature of the contemporary surfing, and also because surfers and shapers were busy bug-fixing the existing designs.

In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, shapers such as Reynolds Yater, Grubby Clark, Midget Farrelly, Scott Dillon, Bob Cooper, and Michael Cundith (who is thought to have stumbled upon asymmetry independently from the aforementioned and by accident while repairing dings at Owl’s Surfboards in California in the late ‘50s) implemented asymmetric features into their designs. The resulting cross-pollination led to the “hook board” – an asymmetrical design with one tail end shorter than the other forming a hook shape – and later on with Cooper’s ‘67 Blue Machine, which featured an asymmetric fin set up. Despite evoking the curiosity of some (particularly Dillon, who went on to produce a series of asymmetric hook-tailed boards), all of the aforementioned board makers turned away from this design concept within a handful of years.

Windansea local, Carl Ekstrom, who’d also been experimenting with asymmetry at the beginning of the decade, independently from the others, applied for a patent on one of his asymmetrical designs in 1965. His request was approved two years later and he went on to shape a series of asymmetric boards, eventually selling the rights to Jacobs Surfboards and California Company Surfboards. This more professional approach and dedication has granted Ekstrom an official claim for pioneering asymmetric designs. Yet, no matter how he and other prominent surfer-shapers such as Bob McTavish, Nat Young, Peter Townend, and Mark Richards utilised asymmetry in their boardmaking, the idea still didn’t click with the general surfing populace. It was only when Californian Ryan Burch rode one of Richard Kenvin’s, Ekstrom-shaped asymmetrical boards nearly a decade ago, resurrecting an apropos curiosity over the concept and working on it himself, and with the development of Donald Brink’s designs, that the potential of asymmetry in surfboard design has again resurfaced – and been explored more widely.

Why Was This Development Necessary?

As the concept of high-performance surfing soared in the late 1960s, so did the scrutiny of shapers and surfer-shapers to create a board that could fit (almost) anywhere and respond to (nearly) every turn. Some of these shapers took a different approach to solving these problems, and in working backwards realised that a surfboard did not have to have a symmetrical planshape – it was simply something that had become an unchallenged norm. There were two basic ideas that resulted in the pioneering of asymmetric boards; firstly designing a board around surfing in one direction, like on a point break. In this case all bottom turns would be performed on one rail, and top turns on the other, and so a board could be optimised for these scenarios. The second, and probably more important, is the fact that a surfer’s stance and body mechanics are asymmetric and therefore it makes sense to design the board to take full advantage of both toe-side and heel-side mechanics.

In the case of Carl Ekstrom, who patented a single-fin surfboard with one rail longer than the other, the focus lay in optimising performance at his local break of Windansea, particularly when trying to cutback to the hollow section in the hope of getting barrelled. Although he managed to solve the issue unilaterally by finding a board that worked on his backhand and another that worked on his forehand, it wasn’t until literally merging both surfboards and creating something asymmetric out of it that his surfing became more natural.

Who Was Involved?

Many individuals have tapped into the potential of asymmetry in surfboard design, but only a few have stood by it long enough and had enough success for their work to have an impact on the history of the craft: namely Carl Ekstrom and in recent years, Ryan Burch, Ryan Lovelace and Donald Brink.

California born and bred, Ekstrom began surfing in La Jolla at the age of 7 and built his first board when only 15 years old. Unlike most shapers, Ekstrom’s career went beyond the shaping room, leading him to design furniture, cars, and even shoes, as well as the first stationary wave (aka the FlowRider) which was developed with fellow Windansea local, Tom Lochtefeld in 1991. In 1964, Ekstrom opened his surf shop, Ekstrom Surfboards, together with his wife. At around the same time, he intuitively began applying asymmetric concepts to his boards, which led him to submit a patent request in 65 and having it accepted in 67. Ekstrom closed his shop and steered away from board-making towards the end of the ‘70s, returning in 1999 to shape boards for friends, one of whom was Richard Kenvin – who provides the link on to Ryan Burch’s experiments with asymmetry.

Also born and bred in San Diego area, Burch’s contact with surfing happened at 3 years old but only solidified a decade later. From an early age, despite having the ability to compete at a high level, he chose to head somewhere other than the pro tour – a path that led him closer to longboarding and other less-mainstream designs than a thruster, and which came to shape his wave-riding style and set the pace for his surf-career. Shaping-wise, after spending some time mastering alaias and paipos, he tackled his first longboard at age 20. The next milestone in Burch’s surf-shaping career happened with the release of Cyrus Sutton’s Stoked and Broke film in 2010, which may have fed Burch’s curiosity for alternative surfboards even more. Hungry for experimentation and led by curiosity, Burch’s surfing and shaping evolved hand-in-hand (as a capable enough surfer to be his own best test-pilot) and his interest in asymmetric shapes deepened when Kenvin introduced him to Carl Ekstrom at an art show in San Diego.

South African Donald Brink became interested in surfboard design and started shaping aged 15. Upon moving to California he was able to explore all of the retro shapes that he’d not had access to in South Africa and in learning the intricacies of how these different designs rode he broke down how his own technique and the surfboard’s shape were interacting. His initial explorations into asymmetric design were born from a desire to improve performance when surfing or turning on his heel side and he’s been focussed on stance-specific design ever since. Brink has since established himself as one of the foremost authorities on asymmetric surfboard design, and ships his surfboards to customers all around the world from his shaping facility in San Clemente.

Design Details

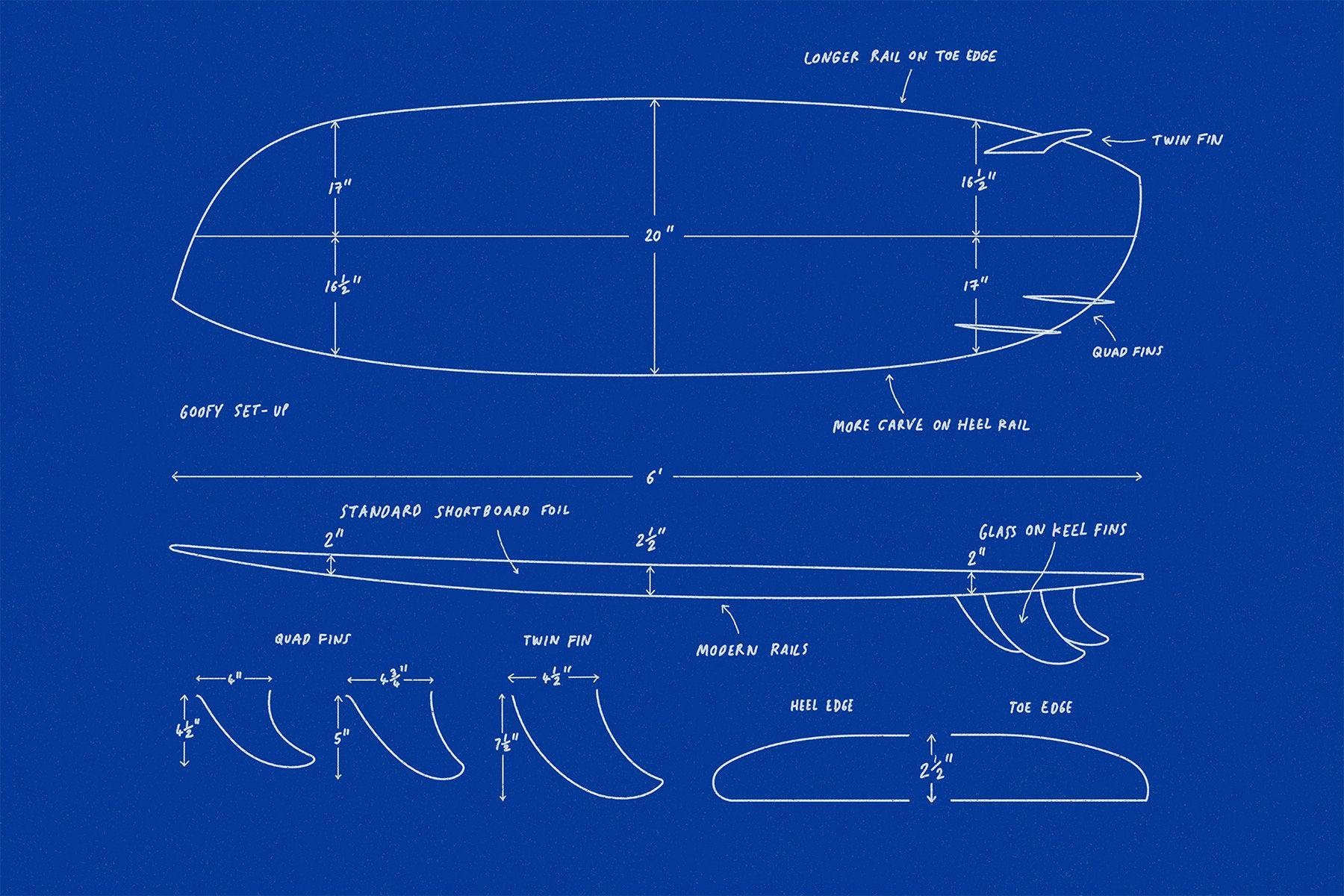

Design-wise, asymmetrical surfboards differ greatly from all other designs in the history of surfboards for the fact that they follow no particular standards and encompass an array of configurations. Regardless of dimensions, number of fins, shape or material, a board is asymmetrical when one or more elements on one side of its central axis differ from the other side. Unlike the asymmetric designs that Carl Ekstrom experimented with back in the ‘60s, which had a much smoother contour with fish-like teardrop lines, the post-2000s models, like the ones that Ryan Burch or Donald Brink have been developing, display much straighter outlines with more acute features, aimed at keeping up-to-date with today’s idea of high-performance surfing.

The toe-side rail of modern asymmetrics are straighter and longer and have less of a pulled-in tail than the heel-side, so as to promote drive, often featuring a single (keel) fin for a loose, planing sensation similarly to that of a fish; whilst the heel-side rail has a rounder plan-shape towards the drawn-in tail, which essentially decreases the size of that side the board and increases manoeuvrability, with two fins underneath to provide more control in tighter turns and shorter radius when coming off the top. The nose section features nearly the opposite configuration: a curvier shape on the toe side for more forgiving bottom turns, against a straighter line on the heel side to boost speed.

These features make asymmetric boards highly rail-oriented designs, that require the surfer to rely less on the fins and his/her hips and more on toe-heel control. Regardless of both board and rider having a bilateral symmetry, when standing on a 90 degree angle with the board’s axis, the way a surfer turns becomes irregular – toe and heel side turns call for distinct movements altogether, the latter being more awkward due to the way our knees, hips, and ankles facilitate forward-leaning motion and recovery. This becomes even more evident in sharp carves. Hence, as much as a symmetrical board may look and feel harmonic and versatile enough for most surfers, so does an asymmetric board have the potential to enhance their surfing in ways that symmetrical surfboards can’t.

Specifications

Avg Minimum Avg Maximum Length 5’7” 6’2”

Width

Nose Midpoint 18 18 1/2” Tail Thickness 2 1/4” 2 1/2” Weight or Volume?