NatureThe Gray Zone

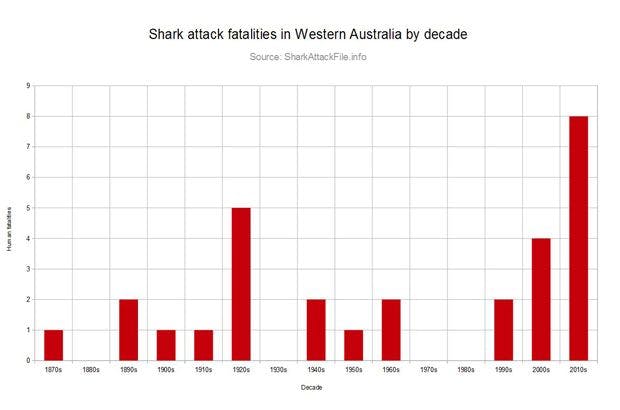

On December 29th 2014 the death of young spearfisherman Jay Muscat from injuries caused by a shark attack close to Albany on Western Australia’s South Western coast took the state’s statistics to ten in ten. Over the past decade ten people have lost their lives in Western Australia as a direct result of a shark attack, and whilst other Australian states surpass WA for shark attacks and other regions in other countries suffer from similar statistics, it is the recent increase in frequency of attacks in WA that has pulled it, unfortunately, into the spotlight.

Why the number of attacks and fatalities has increased, and what to do about the problem, is a complex issue that has often polarized opinion. But this is not as simple as two “black and white” opposing sides with clear arguments and more (just like the sharks at the centre of the debate) a multitude of different tones of gray.

The Problem:

Australia is a nation of beach lovers and avid water-users, be it for surfing, swimming, fishing or diving. The same can be said for other nations and regions where sharks and humans mix in inshore waters, such as South Africa, California and Florida. But in these coastal zones also reside an apex predator who hasn’t evolved much in the past 60 million years or so since the extinction of the dinosaurs. Larger sharks tend to prey predominantly on marine mammals, and many shark attacks are attributed to cases of mistaken identity. Others are harder to classify and in some instances it is claimed that rogue sharks have purposefully targeted humans. Researchers at the Taronga Conservation Society in Sydney have been keeping records since 1791 and have recorded 976 shark attacks in Australia, of which 232 have been fatal – about one in four. In 2013 there were 14 recorded incidents of shark-human interactions, with two of them being fatal, ten resulting in injuries and two lucky victims escaping injury free. By comparison, the National Drowning Report lists 90 deaths at seaside locations for the same period making loss of life by drowning 45 times more likely. But statistics cannot subdue the unshakable fear held deep within many of us that the sight of an angular grey fin rising from the water awakens.

Possible Causes:

There are many suggested reasons for the increased frequency in shark-human interactions in Western Australia in recent years, including a decline in fish stocks, tighter regulation of commercial fishing and the protection of sharks as a vulnerable species in December of 1997 and in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999. White Pointers (aka Great Whites) reach sexual maturity at around 15 years of age, so it is possible that the increase in interactions could be the result of a growth in population since the number of sharks being removed by commercial fishing operations dropped in the late nineties. It is also possible that changes in the populations of whales and their migration patterns along the Australian coastline is drawing more sharks closer in to shore in pursuit of vulnerable whales to prey on. The correlation between location of beached whale carcasses and shark attacks is plain to see, and since 2008 more and more juvenile whales (mostly humpbacks) have beached on Western Australian beaches due, it is believed, to poor nutrition.

Possible Solutions?

4000km or so to the east, the beaches of New South Wales and Queensland (that see more shark attacks than WA annually) have been attempting to protect their beach-going public from the risks of sharks for many years. New South Wales has been using shark nets to protect popular beaches since 1937, whilst Queensland has used a combination of nets and baited drum lines for the past 52 years. The argument against nets is that they are indiscriminate killers, often trapping other large marine life such as dolphins, turtles and small whales alongside their intended targets, and causing most of them to drown. Baited drum lines are much more specific – using a baited hook the size of your arm they only really target large sharks and their aim is to draw these predators away from popular beaches and trap them so that a patrol can either release, tag, or cull the captured shark. When the government of Western Australia proposed a programme of baited drum lines it drew enormous opposition both nationally and internationally. Following a three month trial between January and April 2014, 172 sharks were caught and the fifty of these that were over three meters long were killed by contractors. None of them, however, were great whites. Twenty sharks died on the hooks before crews could reach them, whilst ninety were tagged and released. Last September Western Australia’s Environmental Protection Agency advised the state government against implementing its planned three year programme for using baited drum lines to protect beaches over the summer, citing “a high degree of scientific uncertainty” over the programme’s impact on the white shark population and the subsequent impact on marine ecosystems.

The Reality:

Whatever measures are tabled, and whatever the opposition to them, the fact remains that Western Australia has suffered a (so far unexplained) increase in shark attacks and resultant fatalities in recent years. The controversial proposals to introduce a shark control programme has bought international attention to the state, with many high profile players on either side of the fence. But whilst the debates rage on, surfers, swimmers, fishermen and divers will still be using the sea for recreation and work. They know the risks – it is difficult to enter the water in sharky regions of the planet without having the knowledge of what else is swimming around out there play upon your mind at some point – and yet the draw of the ocean and the joy that it brings them far outweighs the dangers. It is a risk that many of them feel is worth taking, whether they are advocates of active shark population control by the state or environmentalists whose convictions are strong enough to allow them to knowingly place themselves in the natural environment of an apex predator. One way or the other, their love of the ocean and of riding waves overcomes.