Nature, Surf Contests, technologyThe Gold Coast’s Gold

The Sand at Snapper Rocks.

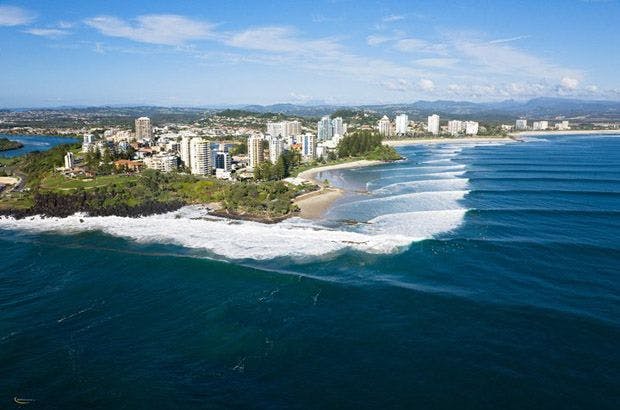

At the end of this month the 2015 WSL Samsung Galaxy Championship Tour kicks off, as it has done in so many years past in its previous incarnations, on the Gold Coast. Every year the eyes of the surfing world focus squarely on the points of Coolangatta at the southernmost tip of Queensland’s Gold Coast, and the sand that sits along them forming some of the best right hand point break waves on the planet. That sand is carefully managed and the pointbreaks of Snapper Rocks, Rainbow Bay and Greenmount are the result of a long-term coastal management system that has also seen the frequency of surfable waves at Kirra (the next point north) diminish significantly. How can it be that one surf spot can be improved at the expense of another, and why not just let mother nature run her course rather than meddling with complex natural systems? We set out to find out why.

Image courtesy of City of Gold Coast

The points of the southern Gold Coast sit on the southern boundary of the state of Queensland, separated from the state of New South Wales by the Tweed River. The Tweed River was vital for transport and the development of early industries at the end of the 19th century, however the sand bar at the mouth of the river proved to be a significant navigation hazard to shipping. This stretch of coast is incredibly dynamic, with approximately 500,000 cubic meters of sand being transported north along the Gold Coast each year by the combined actions of waves and near-shore ocean currents. Sand would move across the mouth of the river and many ships ran aground and were lost. In the 1890s the riverbanks at the mouth were reinforced with rock walls in an attempt to provide a permanent passage for navigation. The sand continued to move across the river mouth, however, so in the 1960s the walls were extended seawards from the coast by almost 400 meters. This blocked the northward flow of sediment up the coast, which became trapped against the southern wall and built up the beach at Fingle in New South Wales. Meanwhile, the beaches of the southern Gold Coast were being starved of sand. The Gold Coast had been developing since the 1920s when improved transport links with Brisbane caused a wave of development – as close to the waters edge as possible. In 1967, 1972 and 1974 the Gold Coast was hit by a series of strong cyclones, scouring sand from the beaches and leaving coastal developments vulnerable due to the lack of a beach buffer. The sand that should have been sat on the beaches of the Gold Coast was trapped at the northern end of the NSW coastline, and was starting to overflow the rock wall and creep around to again cause a hazard to shipping trying to navigate the river mouth. The lack of sand along the southern Gold Coast resulted in the incredible wave that broke down Kirra Point for much of the latter half of the 20th century.

Image courtesy of City of Gold Coast

To redress the balance and protect the coastal residential developments along the Gold Coast, in 1994 an agreement was made by the state governments of Queensland and New South Wales. The Tweed River Entrance Sand Bypassing Project (TRESBP) has the twin objectives of maintaining a safe navigable entrance to the Tweed River and restoring and maintaining the amenity of the beaches on the southern Gold Coast. This has been achieved in two stages – the first being the dredging of the channel at the mouth of the river, with the dredged sediment being used to rebuild and nourish southern Gold Coast beaches. The second phase involved implementing a system that pumps sand from Letitia Spit on the southern bank of the Tweed River, bypassing the river and spitting it back out on the north side in Queensland, most regularly at East Snapper Rocks. This sand is then redistributed naturally and flows north, forming the famed point breaks between Snapper and Greenmount. Sand can also be pumped out at West Snapper Rocks and Kirra Point can also be utilized occasionally as well as a floating dredge to clear the river mouth, whilst the beach at Duranbah is replenished by temporary sand pumping pipes twice a year or following major storms, in order to maintain the beach (and incredible sand banks) here. The downside of this project was the loss of Kirra Point as a world class surf break in all but the largest of cyclones swells under exceptional conditions, as the beach here was rebuilt from 2001 onwards and several years of unusually low storm activity failed to adequately redistribute that sand, leaving the beaches wider than intended. With the return of “normal” weather patterns, the sediment that bypasses the Tweed River now continues to move up the Gold Coast in a more natural manner. This coastline is naturally dynamic, with beaches building up and eroding depending on seasonal wave action (beaches growing in the winter before the sand is moved offshore by waves during the summer – the opposite way round to most beaches around the planet) and in natural cycles over larger periods.

As ever, we humans want to have our cake and eat it: We want the best surf breaks possible as a result of our coastal engineering systems, and we want to maintain sand on the beaches as both a tourist amenity and a buffer against the damage that the ocean can inflict upon our coastal developments. Trying to replicate a natural system that we interrupted in the 1960s and are required to maintain because of our subsequent development of the coastline and desire to utilize it currently costs AU$9 million each year, with the governments of New South Wales and Queensland splitting the check. That’s a healthy amount of money being spent on restoring the natural flow of coastal sediment, but probably an amount that many surfers would consider well spent when presented with an image of Gold Coast point break perfection.