SurfboardsThe Fish Ain’t No Small Wave Sled

When I first began riding Fish surfboards fifteen years ago I was of the general assumption that they were best suited to small, slow moving waves. The design is noted for its speed and capability in crossing flat and fat sections, which helps it to hold a place in our hearts, but who or what was it that led us to believe the design was only good for small surf? The Fish is not and has never been simply a small wave board, and that the majority of the surfing population thinks so is one of the biggest misconceptions of surfboard design today.

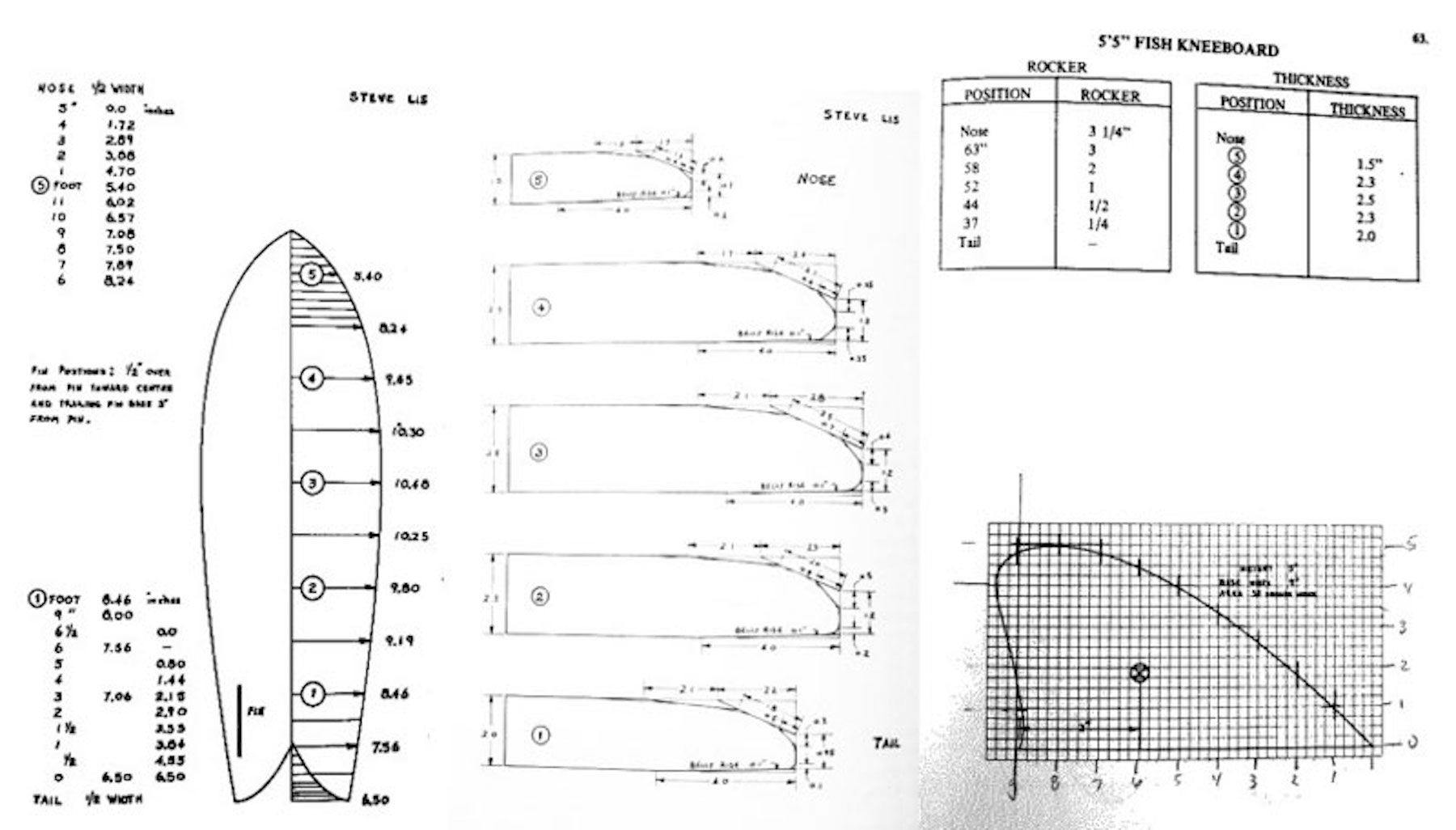

First hewn out of a broken in half longboard in 1967 by knee-boarder Steve Lis in Point Loma, San Diego, it was created for the thick and hollow reef breaks of South County San Diego, California. The Fish has since been heralded for representing a quantum leap in surfboard design which helped in radicalising the shortboard revolution. However, due to the underground nature of Lis and the knee-boarder crew who pushed the Fish’s limits, few understood its importance at the time.

It first busted onto the mainstream scene in 1972 when Hawaiian Jim Blears and style supremacist David Nuuhiwa rode the design to place 1st and 2nd in the World Championships held in small and sloppy surf at Huntington Beach, California. The obvious advantages that the board held began the Fish’s small wave reputation and due to the reserved nature of Lis and his friends, its validity in waves of consequence was seldom heard of, let alone recognised.

What drew me to the Fish most was not its performance as a groveler, but that it demanded less of my own energy and therefore allowed me more time to enjoy the energy generated by the wave. My infatuation grew after first studying its design characteristics… water flows fast and freely between the wide set and straight-toed fins, the lack of curve through the outline promotes fast and slick carving and the combination of its generous volume and classic down rail allows it to sit high on top of the water. The design is based off the belief that less drag equals more speed and knowing this seemed to help in backing my assumption that it was well suited to small and slow surf. But I soon began to wonder, why should the fact that it works in small waves mean it doesn’t work in big waves? And after studying the Fish in earnest, I found that I had it all wrong.

Every aspect of the design is suited to power. The thick down rail was first brought into vogue by Hawaiian “speed surfing” theorist Joey Cabell and his surfing at huge Hanalei Bay; the straight outline and twin-pin tails hold striking resemblance in curve to 70’s single fin guns, which worked best at Pipeline and Sunset Beach; the wide set, wide based and non flexing fins allow the board to store huge amounts of energy; and the thick volume coupled with its short length allows both paddling power and maneuverability in steep and hollow sections.

So why for so long did I only surf my Fish when the surf flattened and fattened? It’s because I took pre-determined perceptions and ran with them. The industry has long and erroneously promoted any board that is a little shorter and wider as a Fish. It is generally considered a ‘fun-board’ alternative to the modern shortboard, for use in small and crappy surf. And for years I along with many others swallowed the skewed idea of the Fish whole. It had to do with a lot of things, not the least of which being savvy surfboard marketers, but at its core the issue was my lack of education. There are many reasons, but I blame my ignorance foremost. I hadn’t taken the time to study the Fish’s history and to learn where, how or why it was created. I didn’t know Steve Lis had made it to surf thick and hollow reef breaks. I hadn’t even done enough time experimenting myself… I didn’t know how well the design would work in large surf because I’d never tried to surf it in large surf.

And then I did… It was at Sunset Beach and I was on a board that always seemed sluggish on my home points in Noosa Heads, Australia. I took the 5’0 out on a clean day for what I thought would be a bit of a laugh, but as soon as I caught a wave and felt the power beneath my feet, along with the control I felt over the board, I knew it was no joke.

Now I’m a changed man. Over the last five years I have been on a literal crash course in learning that the Fish has not yet pushed its boundaries in the big stuff. Or, at least I haven’t reached my limits whilst riding a Fish in the big stuff. And it has been made even more obvious after surfing in Hawaii and Morocco with friends who have dedicated a huge amount of time to the design and have reached a deep level of understanding as a result. It is still an incredibly difficult board to ride, but under the feet of an open-minded surfer and in powerful conditions that allow for the kind of speed and slick carving that the Fish is so well known for, there is an untold amount of beautiful surfing to be witnessed. It’s not hard to imagine that the subtle, minimalist surfing would translate fantastically.