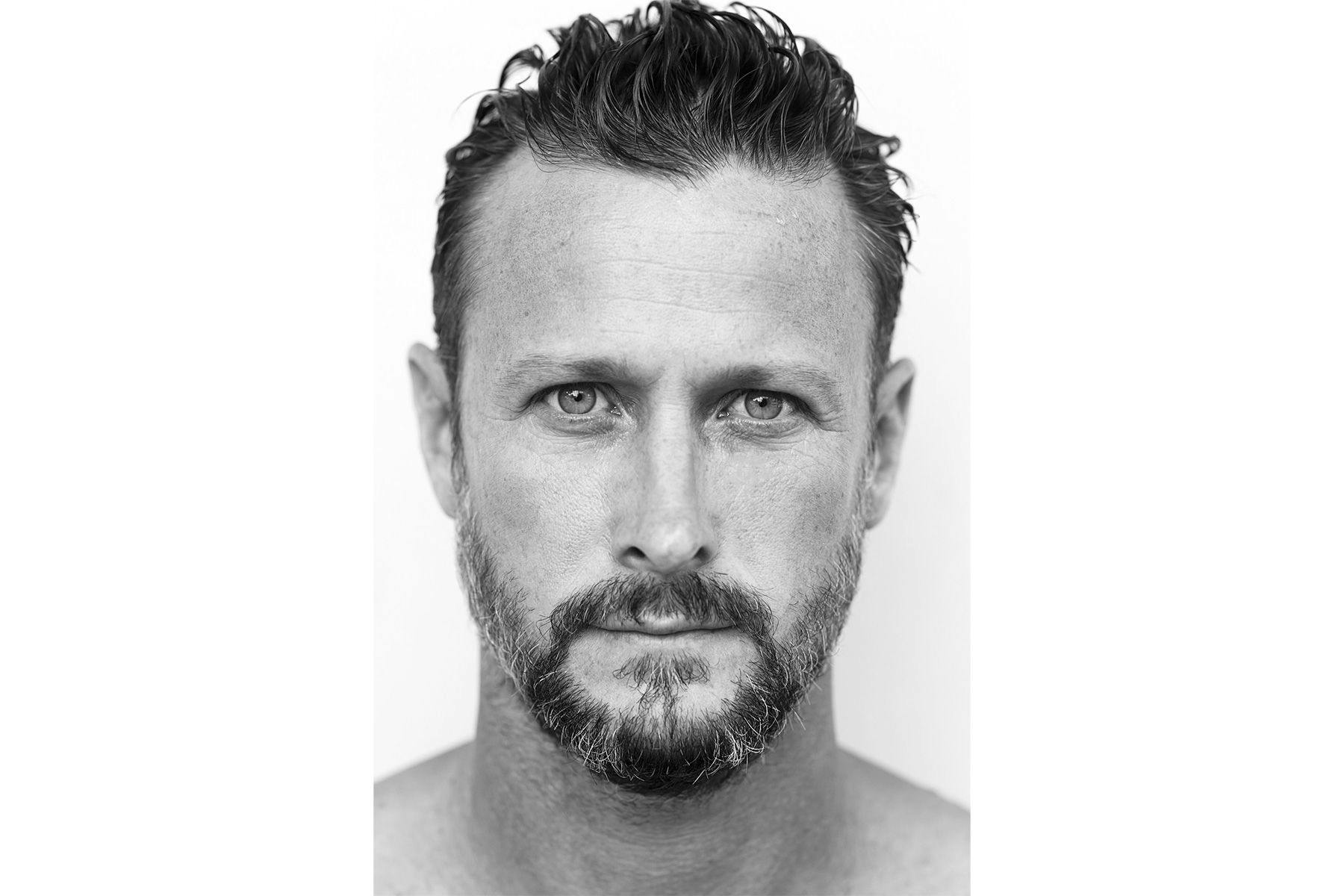

Interviews, People, Photography, Surf PhotographyThe Changing Face of Surf Photography: The Damea Dorsey Interview

Surf photography is a harsh mistress, demanding a mastery of both craft and environment in a competitive and usually freelance field. Few make it to the top, and far fewer made it to the top in the days of analogue photography and have managed to stay there through the digital revolution. Damea Dorsey is a member of that exclusive club of surf photographers, having learnt his craft shooting rolls of 36 when it was still possible to earn a salary shooting for a surf magazine and still hitting the shutter button and capturing incredible images of surfing for a variety of clients today. Who better then, to sit down with and talk about life as a surf photographer and the democratisation of surf photography as a result of digital technology?

Editor’s Note: Damea spoke at length with Surf Simply podcast presenter Ru Hill for episode 48, and the second part of their conversation that focused on equipment for surf photography will appear in an upcoming ‘kit guide’ article.

I’m an average Joe that enjoys the ocean, surfing, and photography. I’ve been combining the all three for over 15 years or so now, and shooting water photography – not underwater photography but in the water – mainly of surfing, is my favourite. I worked with Transworld Surf for about seven years as a senior staff photographer, and I’ve worked with most surf publications and media websites around the world, as well as most of the major companies like Quiksilver, Billabong, Volcom, Hurley, Redbull, etc.

I spent the latter part of my career targeting the highest profile professional surfers on the World Championship Tour for the magazine, and so each year I followed about 65% of the tour schedule, visiting the best places with the best guys. It was a dream job; it was great. If I complained about any of it then everybody would just tell me to shut up!

The reality of being on tour is that it’s the full spectrum, with magical moments and then the occasions when you’re maybe grinding it out. At the end of the day though, it’s a dream job and I appreciated it and took it very seriously.

I was always very aware that I had to do a good job. When you’re doing something like that you have to get up and go to work of your own accord, even when you don’t want to, because there’s nobody telling you to. Any time I knew the surf was going to be shit I had to say to myself “if I don’t get down there then someone else will, and I’ll look bad”, so that was the stuff that was tough, but all in all once you’re there doing it every day you never complain. You’re not sitting at a desk pounding out keys all day in a cubicle – you’re in the sun, you’re in the surf, you’re with cool people, and at the end of each day you’re tired and you feel good about what you’ve been doing.

Although I spent years following the majority of the World Tour the funny thing is, I think I only went to Bells twice – and that was because somebody hired me for a shoot there… There were definitely a few locations that I didn’t visit because they weren’t so lucrative in terms of the content that I could produce.

A magazine needs to put out stuff that people are interested in, so we didn’t spend a lot of time focussing on things like the surf at the US Open – it was more the media hype surrounding it or all the crazy shit that was happening around that event. But I would definitely target Hawaii, where everything is interesting to everybody, from the daily life of what people are doing there through to paddling out at Pipe, Off the Wall or Rocky Point. Everything is amazing there. The same goes with South West France as an American working for an American magazine, because American consumers who were a large chunk of our readership thought “oh, exotic France”. The same went for Tahiti because of its insane waves and interesting culture, so I was always choosing the locations that would provide some good content. I have never been to Rio, or any part of Brazil for that matter, and there is a reason for that – I never felt like spots like that were consistent enough compared to how much it cost to get there. I’m sure that if I went there it would be with a fresh set of eyes and I would get great photos of the place, but I tried to stick to the places where I knew that I would for sure get some good content, because it was a substantial investment for magazines and companies to send a photographer, and it was getting harder and harder to fund and justify as the industry progressed.

Having said that, look at John John’s View from a Blue Moon: the really cool thing about travelling around with guys like Blake and John John is that they know that they’re going to get good surf content, but they are also appreciative of the fact that they’re in another country and that each country has some awesome things to provide and to go check out. If the surf’s not pumping they will be going to check things out and documenting them. I love travelling with those guys. When I was orchestrating trips I used to try to pick guys that I felt could deliver on the surfing, but who would also be up for getting other content such as photos of some gorgeous things. Sometimes getting surfers out of the house is tough, but those particular guys loved it, and it made my job easier.

When I first started shooting photos in the water at Pipeline, psychologically, it was a lot like surfing it. When I got into it there were far less photographers out there than there are now. You have to have, first of all, respect for the location, and then you have to have respect for the people in the water – both the surfers and the photographers. Respect is a big thing there, for obvious reasons. If you don’t respect the surf then you’re going to get torn apart, and then the same with the people! People put time in there and they deserve respect for what they’ve done, and you need to pay attention to those small details about respect. It’s amazing out there, and if you respect everybody then they’ll respect you back and it’s a much better experience. That goes for whether you’re paddling out there or swimming out with a camera.

Standing on the beach in front of Pipeline, it’s one of those arena type settings where you are really close to what’s going on, and it’s intense. If it’s ten foot Pipeline, when it breaks it cuts down through the water and hits the reef so hard that the ground shakes. Some tourists would be standing there next to me and they’d be frothing out, going “you’re going to swim out there??!” and I’m in my zone, just “ssshhhh, I’m focusing“!

To get out to the channel at the end of Pipeline you jump in right in front of the break and there’s a rip that runs from left to right (as you’re looking out to sea). Well, people call it a channel, but you know, when it’s ten foot it’s a raging river and you’re just trying to get near the channel! You have to know how many waves are in the sets and then how far apart those sets are, because if you mistime something you could end up down at Rocky Point you know, via Gas Chambers first. It’s literally a raging river. You really get hyper focused on what you’re going to do, because the very second that you jump in the water it’s game on; you’re using every bit of knowledge you’ve ever had in your life to get in the right place at the right time, to deal with whatever little situation happens, and to move through each step to get to where you want to be out in the line-up, because you need to be at the right spot at the right time, and that takes a lot of knowledge and a lot of experience. It’s not just one of those things that you’re just going to jump out there and it’ll all be great. You get in some very scary situations out there.

I’m really bad at calling exactly how big waves are in Hawaiian terms, but as a generalisation I’d say that 10-12 foot is maybe 3,4 or 5 times overhead – like you’re body height over you. If you ever go up to your bed or your bike and you stand next to it then you’re taller than it, but try laying down on the floor next to it so that your head is at floor level and then when you look up at your bike or your bed you think “hmm, that’s a couple of feet”…it seems a lot bigger. When you’re in the water and your head is literally on the surface of the water, and you’re looking up, it’s just ginormous. And then you look down and think “well, there’s really not a lot of water between me and the reef, and this massive triple or quadruple overhead wave”.

When it’s 5-6 foot you’re going to get a lot more people out in the line-up and it is a channel so it is pretty effortless to kind of slide out and be out at Pipe, as long as there’s not too much north in the swell, like a standard day when it’s coming in and you can swim wide of the sets and you’re pretty safe, and you’ve got a longer lens. It’s easy. I’ll come right out and say it; if you know what you’re doing then it’s pretty much easy. When you get in with a fisheye at six foot or so it’s getting harder, although I was always comfortable with it as I’ve been surfing and swimming my whole life. But the average person can get themselves into a pretty stupid situation pretty quickly out there and either get in someone’s way or be in the wrong spot. When that jumps to 8-10-12 foot or a swell with a little bit of north in it, then the game has changed substantially.

I’ve been in the water before, with a lot of guys shooting Pipe, and noticed that nobody was over shooting at Backdoor. One time in particular I saw Kelly go right, and I thought “ok, so he went right, it looked good, and everybody’s really hyper-focused on Pipe, and he keeps going right”, so I thought this is how I can make a point of difference. You need to go and shoot something different to what everybody else is getting in that sort of situation because all of the magazines will have the same thing. So I swam over to the other side of the peak which, you know, at 8 foot Pipe shooting from the water at the peak is like, you get out there and try to get in position, but it’s a little bit more of a run down the line for Backdoor and it’s a fair swim across the peak. Then Kelly took off on this 8-10 foot Hawaiian wave and, this was in the 35mm film days and he’s riding like a 6’10” or 7′ board, a little more gunny, I pushed myself a little further and lined up with and got a great shot. When I pulled out through the back of the wave I looked and right behind is another wave that is way bigger, and I was way inside – because the current pulls you in with the wave. I turned around to go back out and I stopped. Do I race to get under it, or do I turn and go to the beach? I was caught right in the middle. Every second counts in that sort of situation, and I was stuck trying to decide. It was not good. I looked down and it was 3 to 4 feet deep, and there were no cuts or holes in the reef, nothing, it’s just a flat street, and I thought this is going to be REALLY bad. You know when you realise that you’re in a really bad situation? I couldn’t decide which way to go and there wasn’t a lot of offshore breeze or anything, it was calm winds and it was hard to evaluate what was going on in that in-between zone. My only option was to try to swim out and swim under it before it broke, or go in. I had to pick my best option with the least amount of risk at that point. I realised that I wasn’t going to make it under this thing and if I dared be within a 5-foot radius of where that lip landed I could be destroyed. I could be hospitalised. I might die. I was evaluating it as such. So I realised it was too close to get under and I stayed right where I was, but I couldn’t dive deep underwater because I was already right next to the bottom. I just assumed a crash position where I put one arm over my head and kind of hugged the camera body, because I already had some great photos on it and I didn’t want to lose that shot of Kelly Slater. I knew that I might be going to hospital but I had to keep the camera safe!

I braced for impact, knowing that I was just far enough in that it was going to break in front of me. I had avoided the train wreck, but I was still going to be a part of it. It broke probably ten feet in front of me and I just stayed right near the surface. This thing hit me so hard I got whiplash. I saw stars and got violently thrashed about. It was like a car accident with the seatbelt off. I was getting thrashed dramatically, and I was just hoping that I wouldn’t hit the bottom or collide with the rock towards the inside.

You get pressed in towards that current that runs across the beach and back towards Pipe and Ehukai, and at that point you either try to make it in to the beach, or you’re ok and you go back out. I gathered my senses and checked where I was, held my neck, and really was rattled but I was like, “I’m alright, and my camera’s good, I didn’t lose my fins,” and the current was flying along and I had to make a decision to go in to the beach or cut back out into the channel. I carried on back out and came around, and this next wave came and I was right in position, and Kelly was on this one (a bit of time had passed, but not that much) and I was right back in position. Kelly took off on a left at Pipe and I was right there and got another shot of him, and I swear he kind of looked and recognised me because I was the only guy on the right a couple of waves before, and now I was on the left. I got a shot and he paddled back past me and he was like “was that you on the right?” and I said yeah and he was like “hrphh, I didn’t think you were still out here!”. I couldn’t quite believe I was still out there either!

Back in the days of shooting film, that experience made me feel that I could do this, that I could tough it out. When I got back in that afternoon though I was like “ibuprofen, ice”… I had a full case of whiplash and it hurt so bad.

When I got that roll of film back from being developed it was like Christmas morning!

When photography was still analogue, if you were going to work and be a professional you really needed to know what you were doing ahead of time, so you needed to educate yourself. I didn’t go to school to study photography so I spent a lot of time educating myself, talking to mentors like Larry “Flame” Moore at Surfing – he helped me right from the beginning. Those experienced photographers gave me some vital tips, and I would read up on it and then take a roll of film and go shoot with my friends. You had 36 shots – compare that to nowadays. I have space for over 1000 photos at any one time on my camera. Back then, I only had 36 shots. You didn’t pull the trigger for just anything, you really had to try to time that moment so that you could maximise the amount of time you’re in the water. You had to get to the point where you would shoot a frame and know that you weren’t going to get a blacked out mess or an over-exposed shot and so you had to be like “ok, so when the light conditions are like this, I make note of those conditions and if they change whilst I’m in the water I should adjust accordingly. If I’m shooting in the barrel it’s going to be like this, and if the guy’s doing open face turns then it needs to be this.” So the variables are always changing and you did your best to assess what was going on and keep your notes, and then develop the film and compare your notes to what you got back.

Films would come back from the lab with no information on them, so I’d number the film rolls and I’d have notes for each one.

Nowadays there’s metadata with all of the information on the image file. With film, it doesn’t say what lens you were using, it doesn’t say what your shutter speed or f-stop was…I mean, the film says what ISO it is and what kind of film it is – Velvia or T-Max maybe. It would say these things on the slides that you got back, but it didn’t have any other information – you had to know that. My memory is terrible – I had to write that shit down!

With the advent and advances in digital photography, that learning curve has dramatically shortened. It’s become a lot easier. Now, you pick up a camera, press the button and just look at the back and if you have a basic understanding then you can tweak some things around and figure it out. Beyond that it just comes down to people having a good eye or getting creative and then experimenting with those things. You could spend the whole day and shoot a thousand photos. If I shot a thousand photos back in the day on rolls of film with 36 exposures that’s almost 28 rolls of film! Even just say for 300 photos…tiny rolls, it would cost like $7.50 per roll just to purchase that film and then another $7.50 to develop it so you’re looking at the best part of $15 just to see how your 36 photos came out and $125 for all 300… If you went on a trip and came back with 75 rolls of film – and I was lucky enough to have the mags pay for my film and dev costs at the time, because I had proven myself enough that they’d pay for that – if anything was screwed up then you just felt like such an idiot. Mistakes happen, but you try to minimise them. Nowadays it’s like there’s nothing to screw up, you just fire off thousands and thousands of photos and pick the best one.

People ask if, having a career that I love and that I invested a huge amount of time in learning the ropes of, I feel like people new to surf photography these days have an easier ride and haven’t had to put in those hard yards. That was my kind of bitter attitude at the beginning; I just felt like this is ridiculous, you don’t know what you’re doing and so on, but at the end of the day I just had to remove myself from that because it’s just a negative way to look at it. It is what it is, and there are talented people out there that, even if they had learned it in my time, would still be and are amazing now. You just have to accept what’s going on and move on with it. I did have that kind of salty, bitter feeling like “screw you, you don’t know what you’re talking about!” and then I’d see a new photographer show some good work and I’d have to say “hey, that’s pretty good!…..But still… you didn’t go through what I went through!” Their experiences will change for them later on.

I think the thing that really did it for me was just how devalued surf photography became. Back in the day you’d get a good photo and you felt like you’d worked hard for that good photo and it was valued as such. Now, you have really good photos and you’ll be lucky to give them away. I’m looking at it as, this is a really hard photo to get, and then nobody wants to acknowledge that or pay for it or do anything. I had to let all of that stuff go and just think that I like that photo, it’s my favourite and I’m stoked, whether you want it or not. And then they say they’ll take it for free, and I think I’d rather sit on it and keep it for myself! But the nature of that beast has changed dramatically; that whole industry. That’s why I took some time off, so I wouldn’t be the salty, bitter old dude.

I’m actually more out of the loop now than I’ve ever been in my life, regarding surf photography and films. When I worked for the magazine I was very much on the pulse of everything, because I had to be and that’s what the magazines do. If I was out on the road or stuck in one place for an amount of time and got out of the loop then I’d come back and immediately be updated on what’s going on as part of my job for the magazine. Now, it’s a whole other job trying to keep up with everything, and I’d say that recently I’ve dropped off and fell out of touch more than ever before. It’s kind of a semi-retirement. To get excited about that side of surfing and the industry again I needed to remove myself for a while and then I could start to appreciate it again, and that’s what’s been happening as I went through a period of doing some other things. At the end of the day, I accepted all of the change that’s happened in the surf industry and the fact of the matter is that I just love doing this job. So my advice to anyone in a similar situation is just do what you love to do, and see what happens from there.

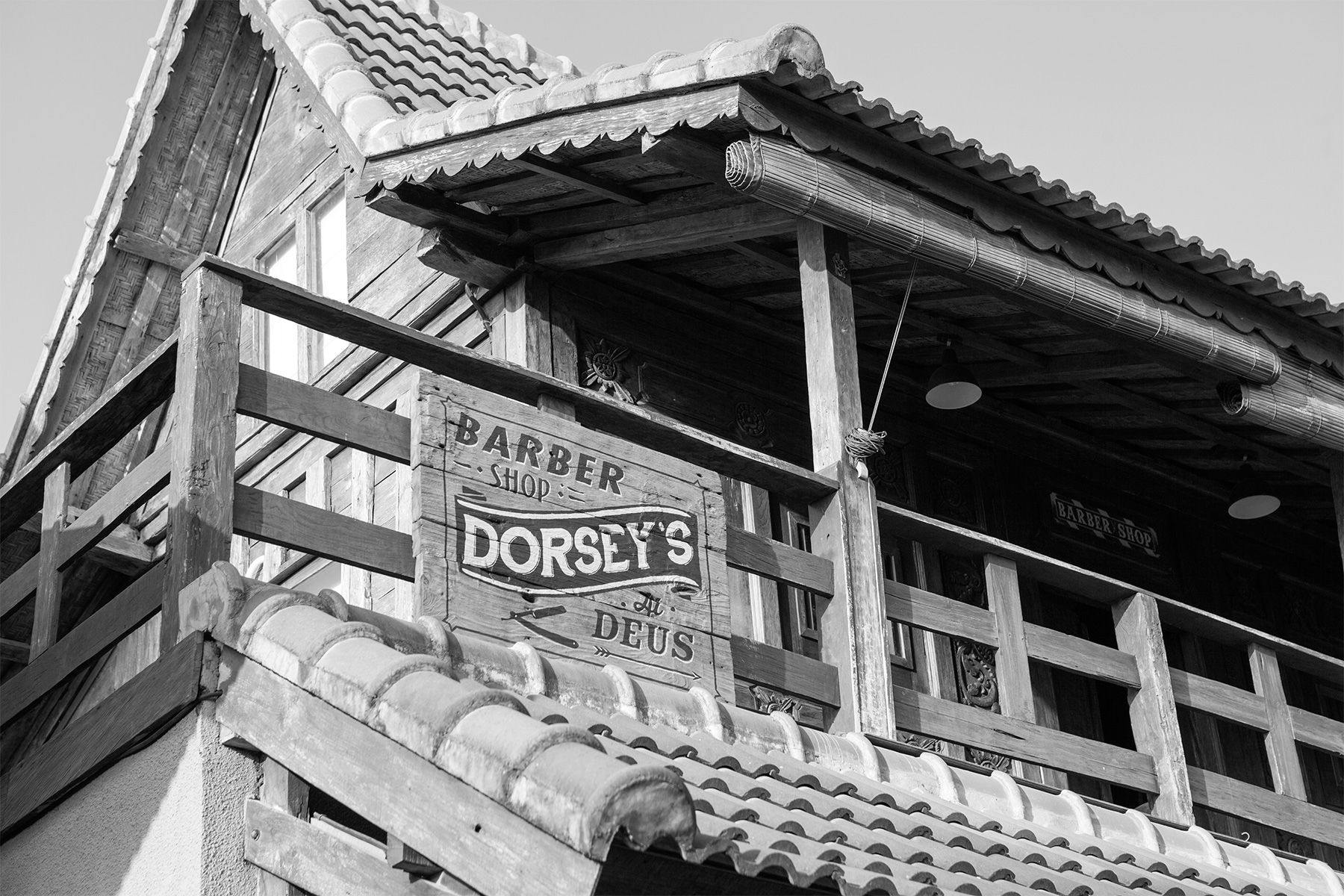

I live in Canggu, Bali, now. Bali’s always been a really special place for me. I travelled all around the world and Bali has a really nice feel; it’s a nice in-between, and the end of the end of all of this is that Indonesia has amazing surf. It’s also not too hard to access that surf, and it’s relatively inexpensive to get to and it’s warm. When you’re in Bali itself you have all of the amenities of the Western world and all of the culture of Bali, plus I get the interaction of friends of mine from all around the world; it’s a really great hub. I have European friends come through, American friends come through occasionally, and lots of Australian friends visit… Bali is just great. We’ve got amazing food, a lot of things to do, the cost of living is relatively inexpensive compared to other places, and it’s comfortable. I was really able to shut off and sit down to figure out what I wanted to do next in my life when I moved here.

When I took that time off, to focus on some other things that would maintain my lifestyle so that I could still shoot photos, I stopped shooting professionally…not completely, I still kept doing jobs, but I pulled back a lot so that I wasn’t stressed out by the things that were happening and just let it be. I’d end up shooting with some tourist guys at a resort or on a boat trip, and at the end of the day they’d be looking over my shoulder going “OH MY GOD! Is that me?!” I’m not shooting Kelly Slater or John John or anything, this is Joe Schmo, but he’s so freaked by something pretty average that it felt good again. I started doing that for a while and it made me appreciate just the whole process of hanging out and shooting photos and enjoying it and not making it too stressful or taking it too seriously, and just having fun again.

At the end of the day, if you’ve got a skill and you have a passion for it, you can be the best if you drive to be the best. Surf photography is an amazing hobby, it’s an amazing lifestyle, it’s a great career, it’s whatever you make of it and it’s fun. At the end of the day, the thing that surfers used to say to me when I was younger was “how do you not, grab your board – how do you grab your camera and shoot photos when it’s good like that?” and to this day I still get a lot of satisfaction from getting a good photo of somebody. Being in the water I still need to challenge myself to be in the right place, to meet up with this person at this exact moment to capture that great image. When it all comes together and I’ve done what I set out to achieve on this photo I feel good, I like what I’ve produced, and the person in the photo is just ecstatic – even guys that get photos every day – I’m trying to up the level of my work to where they’re impressed. You know you’ve made that happen and it’s not just luck, it’s an effort and a skill.

One thing that I love is challenging myself in the moment when everyone’s not seeing any opportunity and then turning it into an opportunity. That was one of the things that I learned from working at the magazine – if the magazine’s paying for a trip then they want some photos, so I would work and try really hard, and at the end of the day I want the person paying for the trip to like what I produce. I go out and challenge myself to get a good photo in an environment where you wouldn’t necessarily think you could, or an image that somebody that doesn’t surf will appreciate maybe. If you pull that image out of its context and put it in another environment it can be gorgeous just the way it is, with no wave, nothing going on, maybe it’s just stunning lighting.

Nowadays I think that you have to be a complete package and be an entrepreneur – you have to be good at what you do, good at self-promotion, and good at business. You have to look at so many more things and become a one-man business that really has to do all of it, not just be a good photographer. In the past, when salaried or staff or doing jobs for the companies, a lot of the parts of my work were simultaneous, like I was working for the magazine documenting the tour but I’d get good free-surf photos and sell those to the surfer’s sponsors. That helped to subsidise my income, which was perfect. Nowadays there’s not as much money with the magazines or the brands, but when I was making that money then if I got a photo of an average person I would just give them the photo. Nowadays, since there’s less money available from the media outlets or the companies and Joe Schmo needs content for their personal instagram and social media, then they actually find more value in it and they’ll pay money for that. So now I subsidise my work by selling photos to Average Joe. I didn’t use to, but I need to pay for my equipment because it gets destroyed in the ocean! You’ve got to get some money back to let you continue to do this, and a lot of people new to the game don’t realise that until their camera dies or until the saltwater has damaged something and they realise that they’ve been shooting photos and giving them away, but now they can’t afford a new camera body. Then they have to go back to hardcore work for a while and stop their hobby while they save that money. You don’t have to charge a person a million dollars for a photo, but if you charge some money then at least you’ll be able to recoup the costs of your equipment and if your work is stunning and you can find other professional outlets to earn more income from it then you have to capitalise on it to turn it into a career. I think that there used to be good photographers, and then people who would help them to be better businessmen. These days you have to be the complete package, and all under your own steam.

To enjoy more of Damea’s stunning photography, take a look at his website or instagram.