UncategorizedSurfboard Construction Pt 2

In the final part of our surfboard construction series, we discuss the skin of the surfboard, new technologies and debunk a commonly believed sandwich construction myth.

So lets go straight in with the skin.

Traditionally made from fibreglass, or fibre reinforced plastic (a polymer to be precise). Fibreglass is actually a trademark, like Hoover or Kleenex and so isn’t strictly the name of the material. A fibreglass skin is actually a composite material, made by soaking woven glass fibres with a liquid plastic resin, which then hardens. The fibres provide the strength and stiffness, whilst the cured resin binds the fibres together, and becomes a waterproofing. There are two types of resins used in this process, the first is polyester and the second is epoxy – if you ever hear someone say that fibreglass and epoxy are two different materials, politely correct them; both are fibreglass.

The two resins do have differing properties, so lets start with the more traditional option of polyester. Polyester resin has been used in boat building for many years and so its cheap, quick and easy to work with. You can also add chemicals to control the speed of hardening. There are a few downsides; it’s really smelly and the hardening agent is extremely toxic, which makes the glassing room a not so pleasant place to have dinner. Polyester can’t be used on polystyrene boards as it melts through the foam. As time goes by, the polyester resin becomes more and more brittle, and is likely to crack. We mentioned in part 1 the yellowing of boards being mostly cosmetic, this time a yellowing board may signify a weakening in the stiffness and flex pattern.

Consequently, epoxy is a much better resin for surfboard construction. It has a higher strength to weight ratio, and is more resistant to cracking compared to polyester as it ages. Epoxy also works better as a bonding agent within the construction, it can have a 20% better bond and so de-laminations are less frequent in epoxy boards. Epoxy doesn’t degrade in quite the same way as polyester, it doesn’t yellow as fast, and also any yellowing is more a cosmetic downfall, rather than a reduction in the boards integrity.

The problem with epoxy comes down to the price; 3-4 times more expensive than polyester. During the drying process its not as controllable, and this process can vary with humidity and temperature. There also seems to be more people allergic to epoxy, than polyester; a small number of companies are working on ways to remove the chemical causing this sensitivity, but nothing market wide yet. Epoxy can be used with any of the core materials, and there are many odourless versions available, and so day to day its a much agreeable process for shapers.

The most common fibre found in surfboard construction is glass, and strangely it’s the same stuff you find in your home windows. There are several variations of glass; E-Glass is the most common (the E stands for electrical as the product was originally formulated to carry a current). You may also hear of S-Glass; the S stands for strength, and using S-Glass can make your board up to 10% stronger and stiffer under the same weight, however it’s more expensive and not as common. There are two other fabrics used commonly; Carbon Fibre and Volan glass. Volan glass is actually a treatment, kind of like scotch guard; E-Glass wasn’t proven too well in a marine environment and so is treated with different materials to counter that, and Volan became the scotch guard treatment to keep the water out. E-Glass was the standard in boat building throughout the sixties, but because it had to be chemically treated, the weave was thicker and soaked up a huge volume of resin becoming very heavy on completion – which in the log/longboard resurgence recently is the favourable option.

Carbon fibre is the opposite of this; it has a huge strength to weight ration, it’s incredibly stiff, but can be brittle under compressed – sometimes its mixed with kevlar to reduce the risk of shattering; becoming carbon kevlar. Weight for weight carbon soaks up more resin, but because it is so much stronger, you can use an infinitely lighter weave of cloth to get the same strength. There are a number of problems with carbon; its expensive and often black in appearance which may not be aesthetically pleasing to some (and can melt your wax off in warmer climates). Also it is very stiff, and a pure carbon board has almost no flex, though again some people like that. There are a couple companies that make pure carbon boards, like Black Dart and Aviso.

Carbon is not commonly used as the sole material; typically you see strips of carbon lining the rails or in the stringer. All of these fibres are typically measured in weight per square yard of a given thickness; 4 or 6oz are the standard weights, which means 4oz per square yard or 6oz per square yard. Usefully a square yard is similar in size to a standard shortboard, and so the calculations are quite straight forward; the only complication is that those are dry weights, so a good glass job should probably match the cloth and the resin about 1 for 1 – so the skin on a shortboard with a layer of 4oz cloth on the deck and bottom plus 4oz on each side of resin, would be about 16oz or (1lb) in weight – that is then on top of the 1-3lb core we talked about above.

Now the downside is that single 4oz on the deck and single 4oz on the bottom would be quite weak, so you could use more than one layer on each side, and can quickly triple the strength and stiffness of the board for only about a 25% weight increase. This is where the core and skin’s relationship comes together; by having a lighter core you can use more fibres and resins to make a stronger board for the same weight. There is also a technique called vacuum bagging which sucks out a lot of the excess resin, as you don’t need a huge amount of resin to hold the fibres together, so again reducing unnecessary weight.

There is one type of skin material that is not a composite; our old friend wood. Wood skin boards look beautiful, but as mentioned in part 1, it’s a heavy material. So wood skins need a light core in order to remain functional – Grain and The Imaginary Surf Company are making hollow all wooden boards that are strikingly beautiful, and often the weight increase isn’t dysfunctionally so, and can be something unique.

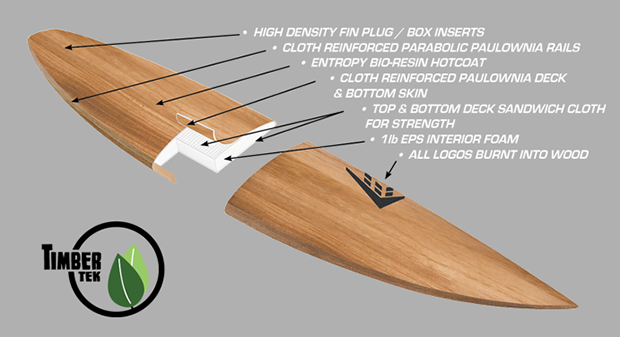

FireWire have recently brought out TimberTek; a very light EPS core (a 1lb cubed density core) with a thin skin of paulownia wood on the deck. They are not solely wooden skins as they also use layers of fibreglass to strengthen them.

Taking several materials, capitalising on their qualities and layering them up is known as sandwich construction, and even though all surfboards are made using this method within the industry we tend to mean multi-layered skins.

The most well known sandwich construction is probably the SurfTech surfboard, they use a light EPS core, epoxy resin glass and a cellulose fibre that creates a light, strong surfboard known as TUFlight. Different companies use different material layer orders and varieties including wood and carbon. Epoxy resin is almost universally used to bind the layers together as the optimal glueing agent.

Typically when you hear someone talking about an epoxy board, this is the type they mean; a sandwich construction board. These boards tend to get a lot of criticism from all different corners of the industry, some people don’t like the flex pattern or feel, and at one point there were a lot of shapers concerned about mass produced surfboards stealing their slice of the pie. The internet is full of misinformation and negative reviews of sandwich construction, so it can be difficult to sift through to the actual science.

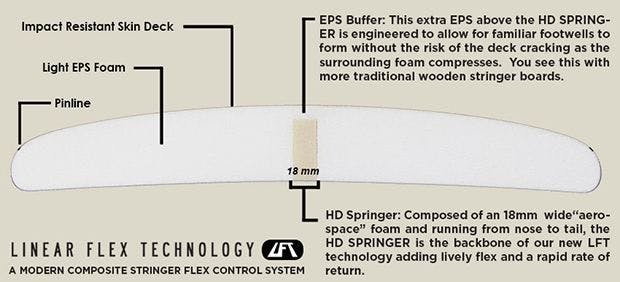

In reality, there were some badly produced boards of this style through the eighties and nineties, but they are difficult to find now. The modern boards have had a huge amount of research and development gone into them by big companies, and consequently a surfboard with an engineered flex pattern can both surf better, and last longer than a traditional surfboard.

Interestingly, the one myth that continues to surround sandwich construction boards is that because they are so light weight, they are too buoyant – thus making it more difficult to engage the rail during manoeuvres. A lighter board would float higher than a heavy one in the water, and a SurfTech could be 25% (approximately 1lb) less weight than a normal board. But considering the weight of the board and rider combined – as an overall package, losing 1lb of weight from potentially 160lbs is negligible. It would be like going to the bathroom before a surf and then complaining you can’t turn because of the weight loss.

The reality is that sandwich boards flex differently, and because of the stiffer skin, they transmit the information from your feet and the wave differently. By feeling different, but not obviously knowing why, people jump on the most obvious reason; which is the weight – but by running the numbers we can debunk that. 1lb of weight may make a difference if you’re Felipe Toledo going for a big air, but to the rest of us, lets drop the prejudice.

So, what should you ride? Well to answer simply, you should ride the board you like most. Kelly Slater uses EPS Epoxy boards when he surfs in smaller weaker waves, but goes back to PU and Polyester in bigger conditions – because he likes the way those boards feel in those types of conditions. PU and Polyester is the cheapest, and easiest way to make a custom board. The mass produced EPS and Epoxy boards are a lot stronger and more able to take the abuse we throw at them. From an environmental stand point, Epoxy and EPS are slightly better, and the sandwich boards can provide the longest lifespan. In reality, the impact of these materials is nothing compared to the CO2 we produce driving up and down the Pacific Coast Highway looking for waves.

The best thing to do is just go out there and demo a few boards, go to shops and demo days, find out what you like and what feels good under the conditions you surf.

At the end of the day, to most surfers the construction of the board doesn’t nearly matter as much as you think, and certainly doesn’t matter as much as the shape and volume.