Interviews, MagazinesSurf Tribes And Surf Tourism

Cape Naturaliste as a Surf Tourism Paradigm

The search for the perfect wave: More than a global phenomenon among surfers, surf trips are a core element of the general “surfing lifestyle,” a fundamental aspect in the shaping of local surf cultures, and a driving force behind the global surf practice. And while surf tourism makes for an excellent way for these cultures to cross-pollinate, this past year’s travel restrictions forced many surfers to reschedule their trips and/or limit the scope of their exploits to their local breaks – a disruption that has left many frustrated, but hopefully also prompted questions on the motives behind the act of surf travel, as well as the mechanisms within our own surfing tribes.

“Surfing populations exist as tribes, isolated by time and space, distinguishable by beliefs, values, history and ecology. These subsets operate as idiosyncratic subdivisions of the wider parent surfing culture,” writes Dr Robert A. Holt, an ethnographer at the University of Western Australia, in a chapter for Springer’s Consumer Tribes in Tourism book published last November where he approaches Australia’s Cape Naturaliste as a surf tourism paradigm.

Branching off a broader study for his PhD thesis on the Cape Crusaders surf tribe, Holt’s narrative-based chapter stands between study and story. Through diarised annotations and 74 interviews with Yallingup, Dunsborough, Margaret River and Perth surfers, he draws on the experiences of the surfers shaped by Cape Naturaliste’s waves to shed a light on the intricacies behind surf tribes and their roles/relations within the global surf culture, namely through the consumption of surf tourism.

Surf Simply caught up with Dr Holt to hear more about the background of his research, as well as his opinions on the interrelations between ‘surf tribe’ and ‘surf tourism’. Readers are encouraged to take the following comments for the case study that they are, using them as the basis for further discussion and reflection on their personal relationships with their own surf community, as well as their approach to surf travel, rather than as gospel truths about surf tourism dynamics.

“I started surfing as a 15-year-old around Perth’s metro beaches, up at Lancelin and down to Mandurah. My first surf trip down south in 1979, well that definitely changed my surfing perspective. During university and my early work life, I regularly headed to Yallingup with my [still] best mates, staying out at the Injidup camping ground under the tea trees, and enjoying the halcyon days surfing the Carpark, Yalls, Bears and further down the coast at Cowaramup Bay. They were formative moments in my life. I moved down to Dunsborough in 1995 with my family, and we loved living on Geographe Bay – a beautiful location and a fantastic community. I consider myself so lucky to have made some wonderful friends down that way though my work, through footy and in the waves. I’m currently down at Denmark, on Western Australia’s south coast, and doing some lecturing work at UWA in Albany.”

At the beginning of the chapter you state: “I am grateful that surf tourism is a significant element of my life.” Later, you recount your first ever plane trip, where you visited Bali with a good friend and “managed to do all the things I promised Mum we wouldn’t—chowing down magic mushrooms, riding motor bikes at velocity around Denpasar’s roads and swilling Bintangs under the moon on the beach at the SandBar.” I gather that this infatuation for surf travel goes beyond wave-riding – an aspect which resonates with many surfers. With that in mind, why would you say surf tourism is important for you as a person, and as a surfer?

[Laugh] I probably sound like a bit of a young hooligan with that opening quote. Bali was all new and very exciting in the early 1980s. Mix that with youthful verve and a surfboard, and that’s definitely a recipe for fun. Answering the question, I have often chatted with my mates about the ‘surfing adventure’. Scoring great waves when you’re travelling as a surfer is a bonus. The spirit of exploration involves observing new places, different food, unusual cultures, seeing people living life in their reality … but undeniably, surf travel is underpinned by the hope of discovering exceptional surf, and enjoying the reward of riding those waves. Travel is such an important avenue for learning, and learning about yourself is a big part of that process. Handling different situations, the unexpected things that travel dishes up, teaches resilience. Because surfers are traditionally hardcore travellers, going to off-the-beaten-track destinations, they often break new ground in discovering tourist hot spots. Arguably, surfing opened up Western Australia’s Yallingup / Margaret River region, well before the famous wines and wineries.

Speaking of the aforementioned region, the chapter you wrote deals with the history and dynamics of the surfing culture in Cape Naturaliste, epitomised in the local surf tribe, the “Cape Crusaders”. One of the characteristics of this particular surfing tribe, and the central theme of the chapter, is the presence of surf tourism both in its inception and its development, exemplified by one of your interviewees in how “the annual surf trip is an important part of our local surfing culture, a great way to escape winter.” Besides the adventurous spirit and the winter migratory flight, what makes Cape Naturaliste a [unique] surfing tribe – what makes a “Cape Crusader”?

In the research, I discovered that the typical Cape Naturaliste surfer identifies himself/herself as a tribal member, and identifies with others in their tribe. They know the local surfers, they know their environment. They connect with the ecology of the region. One of the interesting aspects that turned up in the investigation was the importance of the sense of belonging to the surfing tribe. Moreover, understanding the reality of surfing hierarchies, and where you fit into that pecking order. Interviewing folks from Yallingup, and from 30 kilometres down Caves Road at Margaret River, it was really interesting to see the existence of two distinctive surfing tribes, that were not only separated by time and space, but by their values and practice in the field. The two groups of surfers were all aware of the existence of two separate surfing tribes, and they did suggest a sense of competition or friendly rivalry existed between the tribes. By and large, surfers like to be identified as tribal members, and I’m sure that is not unique to the Cape Crusaders.

From a broader point of view, what have your observations told you about what propels surfers who have great waves at their doorsteps (besides ubiquitous craving for the perfect wave) to travel halfway across the world?

I touched on this in the opening question, with travel being a tool for learning. In surf related tourism, the spirit of adventure is king. Surfers are typically adventurous spirits, and travelling to exotic locations is a key adventure element. I mentioned Rip Curl’s ‘The Search’ marketing campaign in my work, and in my opinion, that concept indeed epitomised scratching the surfers’ itch. Travelling with your mates to exotic places, chasing perfect waves, promotes experiences and enables stories to unfold. Travel really is multifaceted – it’s about the anticipation of the mission, living the journey and then reliving that memory, the good and/or the bad. The photos and videos are vehicles to share those times, but the stories, the narrative that you share with your surfing mates is a wonderful ingredient on the surf travel recipe. I think perhaps that becomes more apparent and more important with age. Maybe that is part of the surf travellers’ wisdom.

You mention how in the interview process you encouraged participants to tell stories – and you sure interviewed iconic characters (film-maker Jack McCoy and Creatures of Leisure owner John Malloy to name a few) who probably didn’t lack tales to tell. Was there a particular anecdote and/or comment that stood out for you?

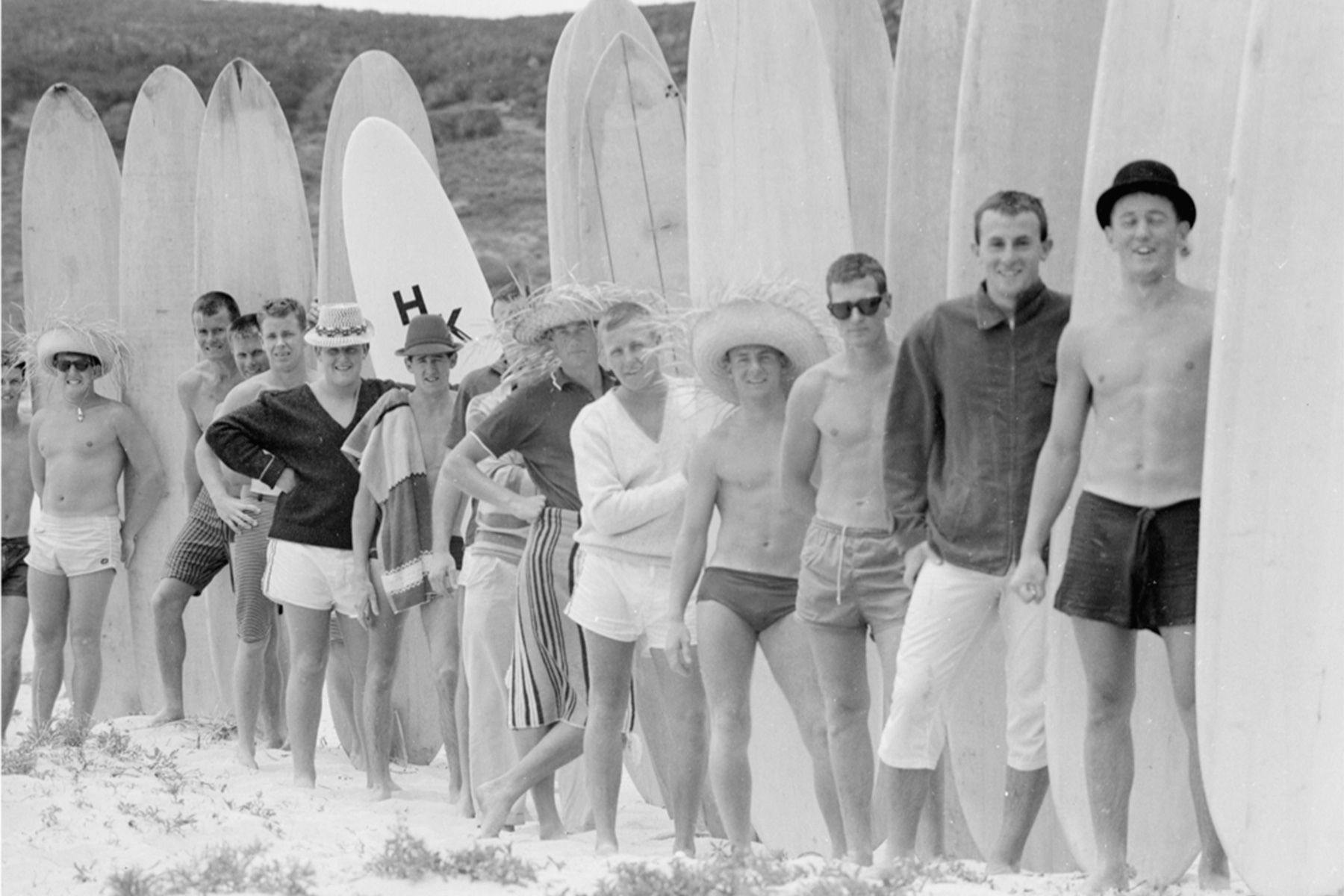

John Malloy’s life story is a corker. Similarly, Georgie Simpson’s adventures and discoveries are legendary. Jack was enlightening and fun. I was really surprised how much I enjoyed unwrapping the historical part of the Cape Naturaliste surfing evolution. The underground movement from the Surf Lifesaving clubs, to the pure, hedonistic lifestyle of riding waves was massive in Australian surfing culture, and this was really evident in South West WA. Sitting down with Kev Merifield, Mark Paterson, Tony Harbison, Len Dibben, Murray Smith, Tommy Trigwell and a host of other surfers from the day was an absolute privilege. Hearing those initial stories of surfing around Yallingup, the stories of adventure and fun being corroborated, the same narrative with a slightly different spin, was so exciting and such a buzz … as a surfer and as a researcher. The tale of discovering the Cape Naturaliste surfing field is without doubt my favourite story.

“When Kevin Merifield, Tony Harbison, Mark Paterson and their surfing friends made preliminary surf tourist visitations from Perth into Western Australia’s South West in the mid-1950s, they recognised the depth of their discovery in a goldrush like scenario. Merifield described his ‘first real surfing experience’ to me during an interview on the lawn in winter sunshine, overlooking Yallingup’s waves. ‘I first came down here on the January long weekend in 1955, with my cousin … we couldn’t believe our eyes as we drove down the gravel, Yallingup was huge!’ Kevin recalled being mesmerised by the mountainous swells, exploding on the outer reefs. Compared to the typical summertime Perth surf, this was a whole new realm. ‘When we got the hang of it down here, [the journey] was on every weekend,’ chuckled Mark Paterson. ‘I remember loading up the cars, putting the boards on top … you could taste the excitement of heading down-south. Surfing down here then, with no crowds, finding new spots, we had lots of laughs, we had lots of fun.’ (…) As wave riding tourists trekked to Hawaii, Africa, Mexico and Indonesia in search of perfect, unpopulated waves, the South West surf secret was soon out of the bottle, divulged by magazines, movies and tales of adventure. The Yallingup waves enticed a fresh crew of surfers to the Cape Naturaliste lineups, immigrants from Perth, from the eastern states and from far-flung California. During the early 1970s, the hunt for new surfing spots between Cape Naturaliste and Cape Leeuwin continued in earnest.”

As a participant-observer, you spent a lot of time hanging out with the Cape Crusaders. Did you come across any unexpected discoveries during these interactions?

The historical significance of the 1970s surfing subculture, and its effect on the tribal ‘vibe’ was an unexpected nugget of the research. George Simpson indicated that the original Yallingup surfers were the ‘hippy surfers’, surf tourists who took a huge leap to move full time from Perth, down south to Cape Naturaliste, in pursuit of surfing the majestic waves. These folks brought with them an egalitarian philosophy, of sharing the waves, taking it in turns. And if you didn’t follow the code, then you were quickly and effectively admonished. This culture of tolerance and respect has always been a significant attribute of the Cape Crusaders. It would be interesting to revisit the study, and determine if these qualities are still central in the contemporary tribe.

Taking the chapter for the case study that it is, and the insights you’ve acquired throughout your investigation of Cape Naturaliste, how do you see surf tourism influencing the development/consolidation of surf tribes in the coming years?

There’s no doubt that surfing tourism has both positive and negative effects on any surfing tribe. If you consider Bali as an example, the way that surfing has ultimately been responsible for changing the dynamics of paradise, wow, that’s an amazing liability. As a global culture, the advent of technology – communication, media, meteorological forecasting, travel method – all make it so much easier for wave riders to find out about surfing locales, and to get there when things are firing. Covid has obviously thrown a spanner in the works for most of us, but clearly, the fortunate few were scoring epic, uncrowded waves during 2020 due to travel restrictions [Editor’s note: for a period of time during Western Australia’s 2020 lockdown, travel between shires within the state was prohibited]

A big factor for somewhat diluting the Cape Naturalise surfing tribe is the development of the Forrest Highway. Perth surfers have the ability to jump in their vehicle, and head down the new tarmac in three hours for a few waves, and then drive back home again. The journey is easy, it’s no longer a complex mission. All surfing tribes have been homogenized to an extent. But they are still a reality. And the truth is obvious – localism in surfing tribes is ubiquitous. Surf tourism / surf related travel hopefully teaches most of us that tolerance in the waves is important. If you travel around the world, surfing waves at far-flung places, then you’d be a complete hypocrite to adopt aggressive localism behaviour at your home break.

In your opinion, why is it important for the regular surfer to understand the idiosyncrasies of her/his surf tribe?

There are no umpires in the surfing field, and that’s a fantastic part of our game. For all surfers to be safe, not pose a risk to other surfers, and to avoid copping a verbal spray from a competitor in the line-up, because that’s what all surfers are at any given time in the surf environment, it is important to know the ‘vibe’ of the surfing tribe. Although that differs from place to place, and that does evolve over time, respect and tolerance should be regarded as important to all surfers. Understanding the quirks of the tribe, or at least being aware of their existence, is significant. Knowing where to go when, knowing the pecking order, knowing the ecology and the dangers associated with the fun of riding waves are idiosyncratic in all surfing tribes. And that’s what makes surfing tribes distinctive.

Likewise, why is it important that there be discussions on surf tourism?

Well, as I have implied, surf tourism is all about adventure, taking the punt of finding and riding the cliché perfect wave, with likeminded friends and family. That concept seems to be indelibly linked to the surfers’ psyche and has always been intrinsic within the surf culture. Discussions about surf tourism open up the surfing community to travel possibilities, not just sightseeing, or going to ‘spot x’ to cross it off the bucket list, but moreover to immerse oneself in the surfing lifestyle, to actively participate while travelling. Chasing the snow is a similar undertaking. Surf tourism tends to, or at least should, establish respect for the ocean, for our amazing planet, for surfing communities and for fellow members of the global surfing tribe. That maybe sounds a bit frivolous, but the people I have interviewed in my research, the girls and guys who have travelled, and who really live the surfing life, they validate this notion. So, I reckon that discussions about surf tourism tend to share the love of surfing, through stories of adventure – and surfers love stories. That’s important.