Interviews, Surf PhotographySurf Simply Interviews: Joni Sternbach

In these digital times a culture is often defined by the imagery that portrays it, and the way that it is presented to the wider world. By and large, modern surfing imagery is action-oriented – so what happens when an acclaimed photographer with no previous connection to surfing decides to document it in a decade long photography project? Surf Site Tin Type happens, that’s what. Joni Sternbach is a Brooklyn based photographer whose tin-type portraits of surfers (made using nineteenth century “wet plate” techniques on large format field cameras) have broken the mold for surf images and seem to have captured the essence of her international subjects, all of whom share surfing as a common bond. This is civil war era photography that involves setting up a dark room on the beach, and Joni has travelled to California, Australia and finally to Europe to produce her images for her exhibitions and book. That’s where Mat Arney caught up with her, and after helping her to carry her dark room kit across the beach he sat down to ask her a few questions about her work.

Joni, your “Surfland” images are remarkably different from the sort of high-octane digital images that surf media is saturated with these days. What inspired you to embark on creating this series of images?

Well, I learnt how to make a tintype in 1999 and I didn’t really intend to embark on a ten-year project with that process. I just went to a guy’s log cabin in upstate New York to learn about what it was and just fell in love with it immediately. You were on the beach with us the other day and watched us pull a plate; you saw the way that people reacted to seeing their image fix on the beach, it just never fails to delight. And so the immediacy of the process and the hand-made nature are these two things that work so brilliantly together to create…I don’t know, the kind of image they create feels a little more soulful – they look a little more tactile and real; they remind you of something that you’ve seen but not exactly. You know what I mean? So, they have this familiarity and yet they’re completely new and unknown. I think those combinations of opposites work so well together to create an object that people find compelling.

How did you first come to have a surfer “sit” for your camera?

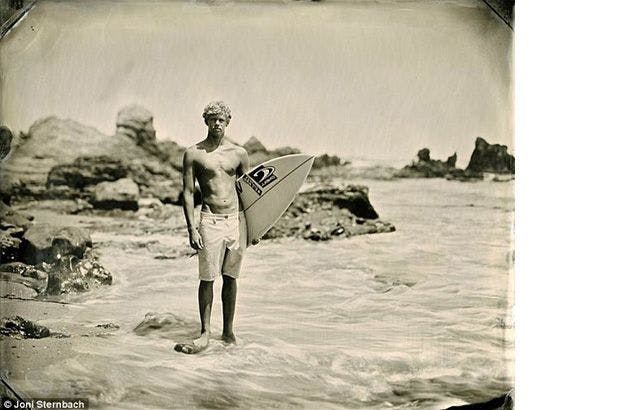

Well, my first surfer was shot from the same bluffs that I was shooting at for the previous five years – I was working the same landscape for a long time, I’ll just say that – and I ran into somebody on the top of the bluff and I asked him if he was a surfer, he said he was, I asked him to pose and he said no. His girlfriend hit him gently in the head and said “of course you will” and he did. So he ran down the bluff while I coated my plate and by the time he got down there, into his rash guard and posed, my plate was ready. There was no communication between us at that point –he was way far away on the beach and there were no directions given. He stood still and was ready to move only when I gave the thumbs up or whistled that the shot was done. So he stood there and we made a picture and he’s tiny in this great big landscape. It was like, “holy crap, this is beautiful”. It was a completely overcast day, my chemistry was probably really crapped out too, and he is this strong, white solid object in this very misty and mushy landscape. My assistant and I looked at each other and said, “We’ve got to do this” and then we made our way down to the beach and started talking to people. I was terrified!

Why surfers – what is it about surfers that interests you?

Exactly, why surfers! There is absolutely no reason why surfers except, in 2002, I was out shooting a landscape of the sea and sky (this was a series I was working on) and I had my camera all set up. It had been a really stormy, cloudy day the day before and foggy. If you were to imagine the sun coming through here, all dark clouds and then the sun sends down these rays onto the ocean, where there just happen to be about 20-30 people in black wetsuits out on the water. They’re not going anywhere, right? And snap, you make this picture and the light goes off in such a way that gives you goose bumps and makes you think that you have experienced heaven. So I took this one picture, and it was not a picture about surfing or surfers, it was a landscape picture. But at that moment, I felt like I had a connection to all those people in the sea because, it was like I could hear them from the bluffs. We all went off on this thing together. I don’t know who it was in the water – I may know them now but I didn’t then, but we all experienced one of those most divine moments of light and ocean. So the reason why I went back to the bluffs to photograph a surfer was because of that moment.

What is your take on the surfing tribe, as an artist making a study of them (us)?

Well, it’s funny that you should ask. So, I had no idea about anything about surfing. It wasn’t until two years into the project that I even looked at a book “History of Surfing,” right, I just went in blind and decided that blind was the best way to be. Because, there’s an innocence to ignorance, right, and I wasn’t really like a surf enthusiast, I was just interested in this collection of people that have one thing in common but otherwise may have nothing in common. And, they’re all different types of people and I could go to this one location with this very elaborate chemistry and set-up and find a huge cross-section of people and the uniting force is surfing. It was, for me, this group of people that fit in so perfectly with this process that I was using. Like, they were a tribe but I didn’t know anything – I didn’t even know that surfing really had such a history!

The “tin-type” images that you produce require large, antique photographic equipment (although not as antique as I originally thought) and an almost alchemic knowledge and skill. What are the processes involved in making these photographs?

Most people who shoot with wetplate, like to use the actual period equipment and materials – it’s beautiful stuff, don’t get me wrong, it’s just very limited and doesn’t really work for what I’m doing here. I do use period lenses in some instances, but if I didn’t have a shutter on my lens then I don’t think that I could make these pictures that I’ve been making.

In terms of the process, which everybody likes to put center-stage, is to me a little bit like pulling the rabbit out of a hat. This trick that I could pull out, but to me the project is not so much about the process, yet the process is the thing that pulls everybody in to the project. So there’s a little bit of a magician thing going on there.

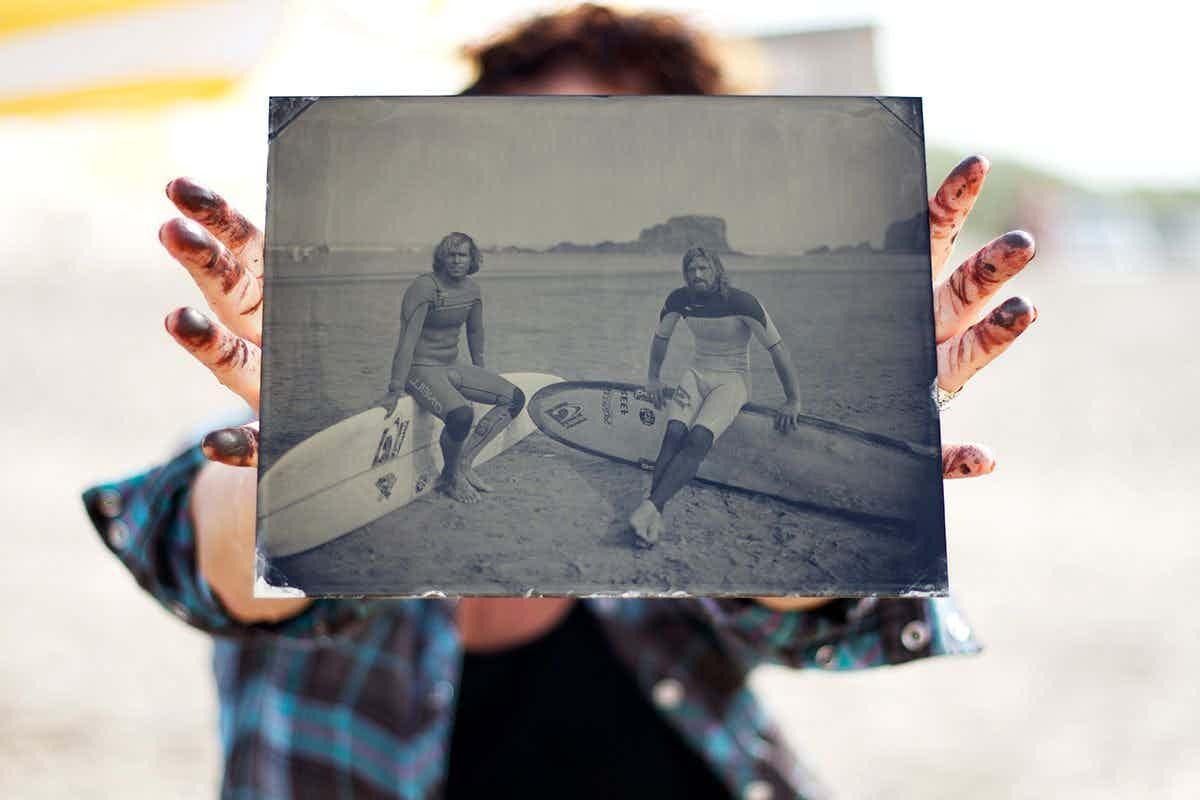

So basically what it is, is a piece of blackened metal that you pour this substance called collodion on. Collodion is gun cotton, ether and alcohol combined with iodides and bromides to make it have tonalities. You pour this on the piece of blackened metal and you sensitize it in a bath of silver nitrate and while it’s wet you take the picture and while it’s wet you develop the picture and while it’s wet you fix the picture (or you can just fix it later if you take it away wet and fix it at your studio) and then it’s washed. The whole thing has to stay wet from start to finish so that’s why my dark box has to come with me to the beach and that’s why I have to haul around so much crap!

And how does this process translate to the beach environment? (Logistical problems with sand and humidity etc.?)

First of all, wind is probably the biggest factor. Wind is not your friend with wet plate. It puts lines on your plate of collodion and it dries your plate out and makes you a little crazy because of everything blowing everywhere, so to me that’s the worst part. Working on the sand is really not so bad – having your office be on the beach everyday and shooting is really the best part, it’s just that you often have to carry your gear over a lot of territory, then it’s hard work.

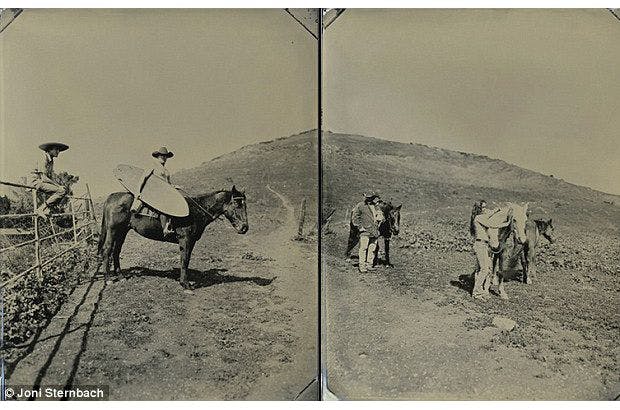

Recent images that you made in California (Horse-mounted ranchers carrying surfboards, and the Malloy brothers with their outrigger canoe for example) bring to mind a “pioneering” aesthetic similar to historic civil war era photographs. Has this been a conscious decision or do you think it is an unavoidable link because of the tin–type process?

That’s a really good question! I would like to say that I was channeling Timothy O’Sullivan and all of those forefathers when I made those pictures, but I don’t really know. When I’m in places like that, I try and feel around the landscape and connect to certain parts of it. When I was photographing the Malloys with their big red plastic canoe, it looked at first a little ridiculous in the landscape. However, when I pulled the plate, the colour of the canoe went dark and the green landscape was kind of misty and so it looked strangely like they were in Asia somewhere! It suddenly went from being California to Asia and, I don’t know, it just had this very out of time feel that I though was really quite amazing. And it was like 40-second exposure – it was a really long exposure, it was really quite dark out.

When I first met Chris he told me about it and he wanted to have a picture with his brothers with it, and we thought about all these places to take it, but it was really like the back yard was the best spot because that’s really where it lives until it goes somewhere for real.

Have you travelled specifically to shoot work for this series or has it been a sideline series?

Oh no, you have to travel specifically; there’s no sideline. This work is all about planning and preparation, and in order to go somewhere you need to source your chemistry, you need to source out all of the stuff that makes “your” kit and for me my kit is very specific now. You know, I went to Australia and had to figure it all out there, and it takes time to figure it out. You have to be somewhere a while, you can’t just “pop-in” and make it happen, at least I can’t! It takes a lot of prep – even just finding distilled water here was a pain! If I’d known then I would’ve ordered it in advance.

How do you select your subjects?

Sometimes they select me!

Explain how you have come to photograph some of the most famous names in surfing?

Well, they all showed up in different ways. I have a friend in New York who introduced me to Kassia Meador and I took her picture in New York but I didn’t think that it was good enough, so when I went to California I got in touch with her and told her I’d love to shoot with her again. She said, “Ok, why don’t you meet me at Donald Takayama’s shop, so we met there and Donald also came out for his picture and it was just one of those incredible days. I just loved photographing him; he was so much fun and a real sweetheart. I feel really honored that I got to take his picture, particularly since he died so soon afterwards, he was too young for that.

He struck a very classic pose as well.

He posed purposefully, that ‘first surfer’ photograph that struck me, also captivated him, he really wanted to embody that pose. So that’s how I got to photograph him. When I was in Australia I was at a gallery opening and I met Dave Rasta and his American girlfriend, and they invited me out to their farm and that’s how I photographed him. Not to forget that his girlfriend, Lauren gave me my first surf lesson. I photographed John John and Jordy for O’Neill, and after the job I snapped off one of my own!

There are some people that I’ve sought after who are really big. I photographed Robert August and Wingnut from Endless Summer. I recently met some amazing shapers in San Deigo, Jon Wegener and Rusty Priesendorfer. I met Tom Curren in California but the shot didn’t come out well, but then I met him again the next time and we did another shot and got to hang out a little bit. I might be able to take a decent picture of him now that he’s more comfortable with me but he’s not somebody that is comfortable having his photograph taken.

What is the most rewarding thing about this body of work?

I think that the most rewarding thing is…it’s like the day in Santa Barbara when I was shooting this guy I’d never met before on this ranch that I had never been to before with this group of people who I had no idea who they were, and there’s a kind of choreography that happens, a kind of flow of events that takes place while you’re shooting that leads to endlessly amazing pictures and at one point they guy that I was photographing said to me, “I don’t know if you noticed, but I think that we made a little bit of magic today,” and, we did. It happened the other day at Towan too. It’s just a series of people come in and things just flow – you move over here and you move over there and at the end of the day there’s this incredible feeling coupled with good pictures. So whatever that is that I just described, I think is the best part of it. You can meet people that you’ve never met before, make a little magic with them that’s called a photograph and everybody is just so happy.

Do you have a favorite image? Why?

I do, I have a bunch. Some are different than others. I photographed Izzy and Lucy Kirkland and also Lucy Thorman the other day. They were up against these rocks and they just, I don’t know, there’s something about this picture. It doesn’t look like any other picture I’ve ever taken. It’s these two women who are caught in time; I don’t know how to describe it. It kind of kills me. Sometimes there are expressions – if you look at Izzy’s eyes, she has super light blue eyes and they went white, so it’s freaky the way that she looks and yet there’s a softness and it looks like if Woodstock were on a beach in 2014 this would be it. They look like free spirits.

Where do you see this project going – will it be an ongoing documentary or does it have an end point?

It probably does have an end point, but it’s not yet. I thought I was done with it – I used to tell everyone that not only am I done with this but also I’m done with collodion! You have a very short collodion life because it beats you up. But I might have a gig in South Africa and I might do a trip to Hawaii, and I think that if I went to those two places and maybe the North of Spain, south of Biarritz, maybe somewhere like that, then it could really be an important document, if I could make it broader. I don’t know if it has an end, it probably does.

Are you tempted to capture Surfers now on different, more modern equipment or using colour photography techniques, or do you think that would spoil your relationship with photographing surfers?

I’ve started to shoot them using film as well; I don’t think that it just has to be collodion. I mean I don’t know if the film will end up being fabulous in the same way that the collodion is, but I love shooting film and it’s nice to be able to make prints.

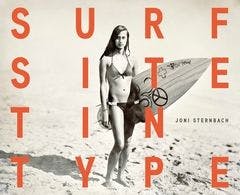

Joni’s new book, Surf Site Tin Type is published by Damiani Editore and is available to purchase here.