Nature, Science & SkepticismProject AIRSHIP

Using Blimps To Spot Sharks

“Given that surfers tend to interact with sharks more often than other ocean users, they should certainly have a voice in how we can minimise the risk of shark incidents. I think it’s important for surfers to make evidence-based, informed decisions when responding to the risk of sharks. Importantly, given how low the risk of interacting with a shark is, most of shark mitigation is about making surfers feel safer when entering the water, and to do this we have to have confidence in whichever mitigation strategy we decide is appropriate. For me, that means rigorous scientific testing under a variety of conditions.”

Those are the words of Dr Kye Adams, a surfer, lifeguard, and marine biologist at the University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia.

Hailing from the small coastal town of Kiama, NSW, Kye’s early interactions with the ocean were deeply influenced by his father and led him to take up surfing at age 12 – laying the foundations to a relationship which developed both into a healthy obsession and a bond of respect.

“I grew up lifeguarding at our local beaches as a summer job, so watching for baitfish or shark activity has always been part of my mindset. Studying Marine Biology got me thinking about shark mitigation from a scientific standpoint. That’s when I decided to do something about it and started Project AIRSHIP”

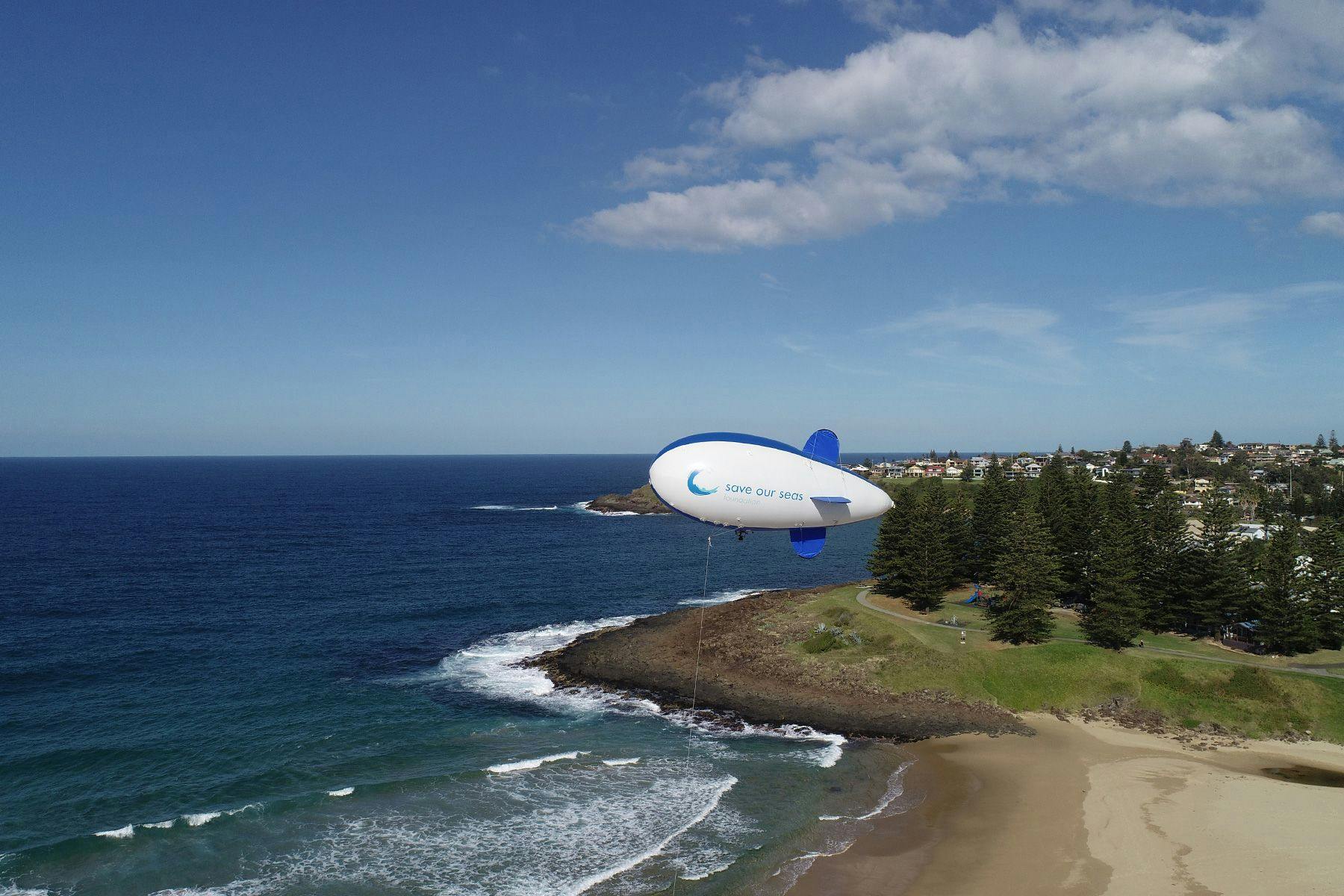

Using a blimp to provide continuous aerial surveillance of the beach, Project AIRSHIP (Aerial Inflatable Remote Shark Human Interaction Prevention) was the result of idea-generation sessions aimed at circumventing shark-nets (which are designed to reduce the number of sharks by catching and drowning them) and finding alternative ways to manage sharks.

“I started Project AIRSHIP as a grass roots not-for profit. The project was initially supported by the local council down at Kiama, then gained momentum with support from NSW state Government, the University of Wollongong and then the Save Our Seas foundation.”

By tapping into the wide-angle line of sight of a camera mounted on a car-sized blimp tethered to the ground, Kye and his colleagues get real-time, high-definition views of the ocean below – which is streamed to a screen inside their hut – and can adequately warn surfers and/or swimmers once a potential hazard is spotted in the vicinity.

Unlike aerial patrols or drones, which have proven either expensive or restricted by low battery life and safety regulations, the current blimp prototype can stay up in the air from sunrise to sunset and needs no license. It hovers silently and safely in winds up to 40 km/h, requires minimal personnel training, reflects no task overload (drone operators have to simultaneously fly the drone and look out for sharks), adds an extra vantage point wherefrom lifeguards can observe swimmers, and produces no by-catch (unlike mesh netting, which despite killing so many sharks, are still the primary method for protecting water-users in several areas). It also incurs relatively low operational costs with the benefit of being used to generate advertising revenue. And, thinking of the future, it provides systematic and permanent data via high-resolution camera captures, which could then be used to build up algorithms for automated shark detection.

Whilst the fact remains that around the world sharks still claim less lives annually than fireworks or drowning, surfing puts us in a higher risk category than the average citizen simply due to increased exposure. Statistics don’t prevent us from being conscientious and sometimes trembling (not from cold) when paddling out, particularly Australian surfers who in 2020 saw their country record the highest number of fatal attacks since 1929 (eight men – aged between 17 and 60 – have all been killed by sharks while in the water off the coast of Australia in 2020). Taking this factor into account, as well as the increasing frequency of shark incidents worldwide and the growing movement to find more sustainable mitigation programmes, Kye and his colleagues put the blimp approach under the aforementioned “rigorous scientific testing.”

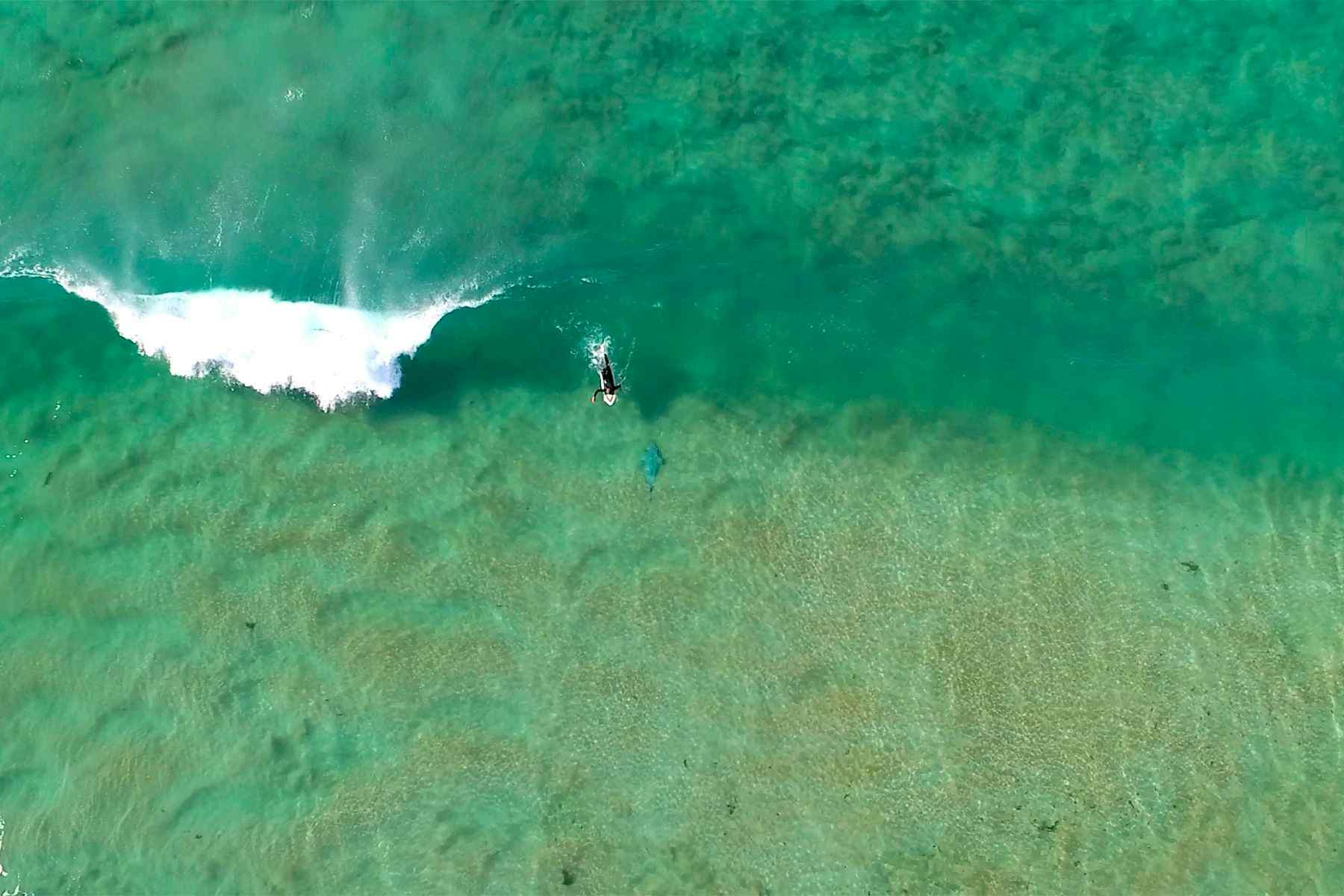

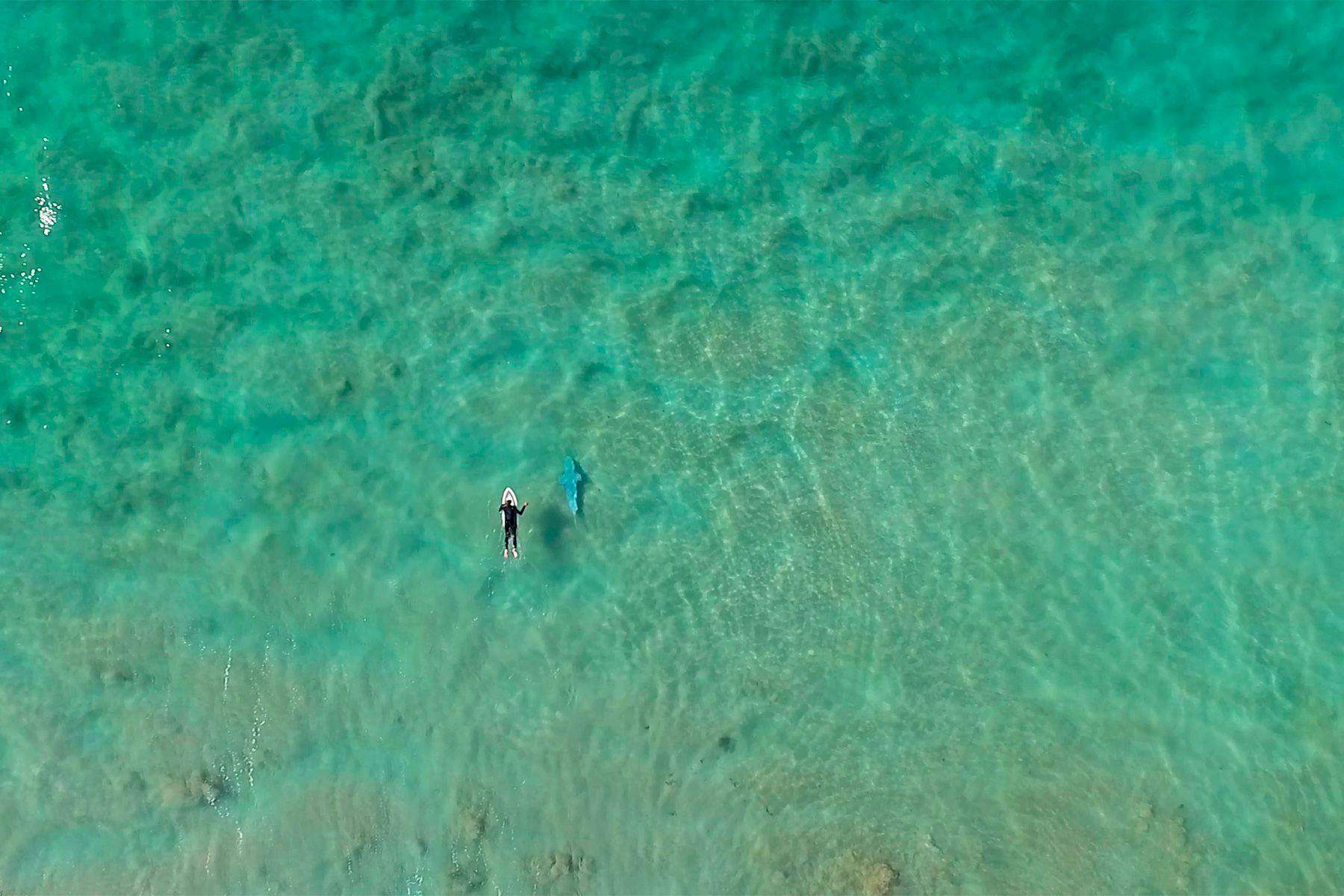

For the study published this past October, the team tethered a helium-filled blimp with a live streaming camera system 70m above Surf Beach, Kiama (a sandy coastal embayment enclosed by two fringing rocky reef headlands) and, on ten different occasions over the course of six weeks, captured footage of a shark-sized free diver swimming across several sections of the nearshore, under various weather and sea conditions. These were then mixed with clips in which the shark analogue was absent, and shown to 20 professional lifeguards to be analysed.

Concerning shark detection rates, the study points to a high probability (over 90%) of lifeguards spotting the shark analogue in shallower areas under good weather conditions (i.e. sunny days and low winds), which tend to be the time when beachgoers frequent the swimming zone. This percentage fluttered the further away the analogue moved from the shore:

“We found that the detectability of sharks is reduced on cloudy days and in windy conditions. These represent less than ideal beach conditions where you’d expect less people going to the beach. In most conditions there is still a reasonable chance of spotting a shark so the risk is still reduced by having surveillance in place. We have also started testing multi-spectral cameras which might improve our spotting rate in less than ideal conditions.”

Like the Shark Spotters in Cape Town, another challenge the Project AIRSHIP faces is relying solely on humans to monitor the footage, which can be fatiguing. Also similarly to the approach in South Africa, Kye and his colleagues are drawing on technology and “have developed an automated detection algorithms that can detect sharks in real-time.”

While the blimp was flying, the team also conducted face-to-face questionnaire surveys with beachgoers, in order to gauge public acceptance of the technique concerning beach safety and comfort with the surveillance method, as well as to gather general views on shark hazard mitigation, including the shark netting programme introduced in New South Wales in 1937.

84% of respondents felt safer under the blimp’s watch, whereas 16% said to feel the same. Similarly, 90% of interviewees said they were comfortable with this surveillance approach, and only 1% reported feeling uncomfortable. Under the question of whether or not the interviewee would ‘choose to go to a beach with a blimp rather than one without, if both beaches were good and convenient’, 67% of beachgoers answered Yes and 13% No. Interestingly, though 27% of respondents reported to support shark netting, 93% said they would prefer that mitigation approaches safeguarded people without harming sharks. When asked if they would like to see blimps at other beaches, 90% answered affirmatively.

Apart from the inconvenience of being stored fully inflated, blimps are proving to be an effective tool for long-duration monitoring of fixed coastal zones. According to Kye, so long as wind and water conditions are taken into account, and local airspace regulations allow, “in it’s current form the project is easily scalable to other locations, with set-up and running costs potentially able to be covered via advertising revenue of the blimp itself.”

For surfers who share their playground with sharks and who can’t shake the mental image of Jaws from their head, he also points out that, though risks can never be eliminated, taking personal responsibility for avoiding shark interactions help more than hinder.

“Easy things to do are to avoid surfing if there are baitfish or a whale carcass nearby, always surf with a mate, get yourself a first aid kit for your car with a tourniquet. If your favourite break is particularly sharky maybe invest in a personal shark deterrent that has been independently tested.”

Shark-human interactions have duly been on the spotlight of marine environment related issues for decades, and this year in Australia more than ever. Fortunately, the further we acknowledge of our impacts on the oceans, the more we become aware of the role of shark populations for its well being. And the better we navigate through misconceptions and fear, the more successful are the ways we find to coexist.

“I think one of the benefits of aerial surveillance is that it gives a good idea of how frequently sharks might come close to shore at certain locations. At our trial site we only saw sharks (grey nurse) when baitfish were present. By having continuous surveillance we can get a better idea of which beaches might be hotspots and better inform people to make educated decisions about where and when they chose to surf if sharks are something that concern them.”