NatureMozambique’s “Reefs of Hope”

If the world is all about balance,then it could be argued that Mozambique justifies its share of social instability by having one of the most diverse coral ecosystems in the world. This republic in the south-eastern corner of Africa has undergone a wave of intense social changes since its independence from Portugal in 1975, and later with the Mozambican Civil War (that began in 1977 and lasted an arduous 16 years). These events reverberated in the form of many socio-economic issues that impacted the country in the years that followed, such as Mozambique’s low levels of literacy, a high percentage of the population living under the poverty line, alarming rates of HIV/AIDS, poor sanitation and corruption. The migration of large populations from rural regions to coastal areas was also a result of these conflicts, as many Mozambicans fled the fighting taking place in the interior of the country and moved to the coast; a transition that created a previously non-existent pressure on the environment along the coastline. Since then, much more attention has been given to this patch of the WIO (Western Indian Ocean) region, and the areas of Mozambique that have been able to sustainably develop communities and an economy around the country’s rich natural resources and wildlife happen to be among the few locations that have managed to stay above the poverty line.

In 2009, I was fortunate to visit this hidden gem in eastern Africa and the warmth of the people combined with the warmth of the water made me want to return a year later. On my first visit to the country, I spent a month in a coastal village called Tofo (roughly 7-hours drive north of the capital Maputo), surfing the uncrowded and perfect right-hand point break of Tofinho and exploring the area’s diving spots. On my second visit, I extended my stay and spent some time surfing a massive swell in Punta D’Oro – a small village near the border with South Africa famous for its long sand-bottom right-hand point break wave – before heading up to Tofo again. On both occasions, what struck me most about the nature of the country was its marine biodiversity. The clarity of the water and the colour and richness of the coral reefs were the perfect setting for long surf sessions, making it an almost surreal experience. Yet during both my visits I was teased by locals and fellow travellers to explore the northern parts of the country – as they said, it would “blow my mind”.

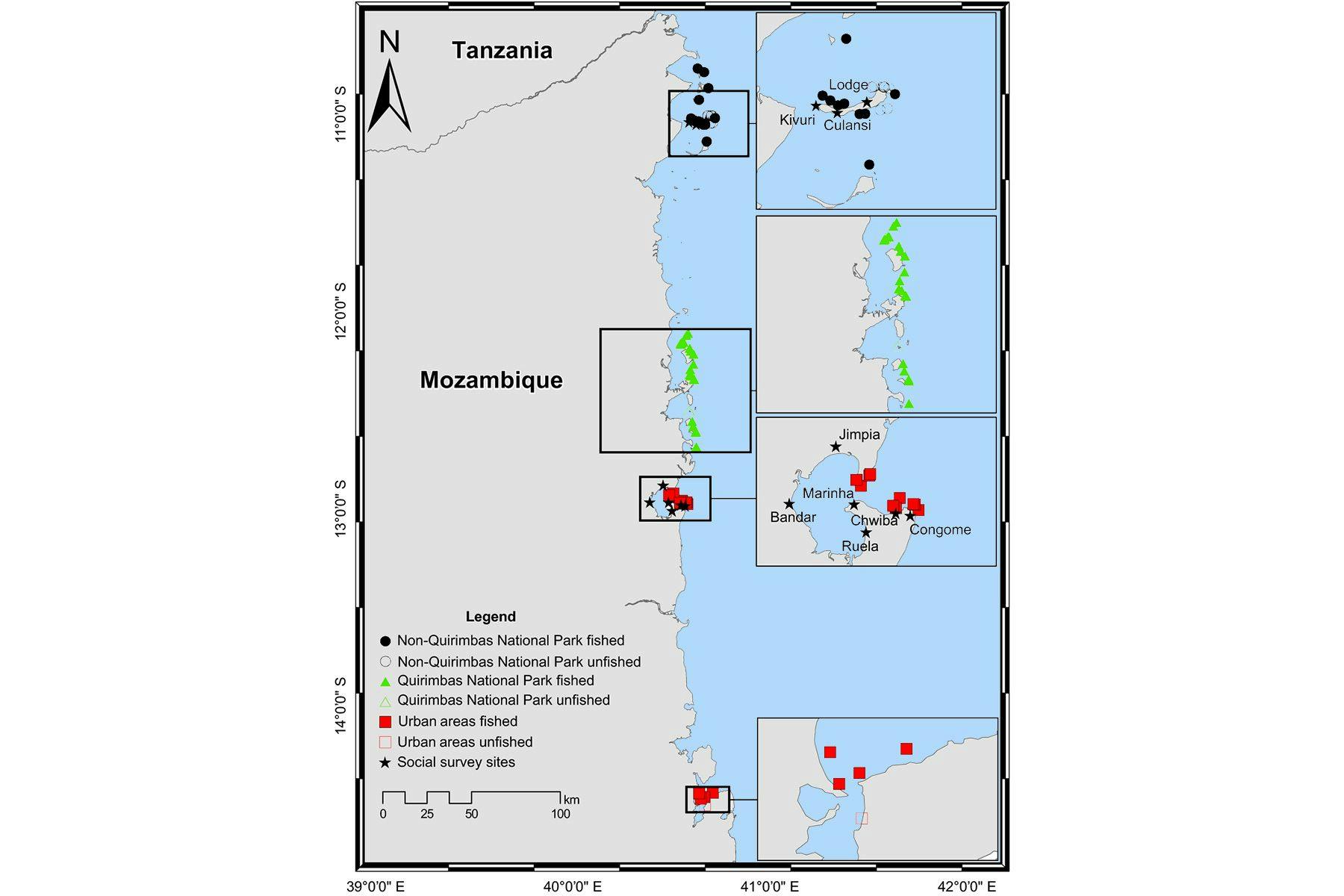

What is referred to as the northern region of Mozambique begins roughly around the coastal towns of Nacala and Pemba, and runs up through the Quirimbas National Park (QNP), all the way to the remote areas near the border with Tanzania. The region’s difficult access is both a blessing and a curse, since isolation helps with preserving the ecology of the area but also presents a challenge for the local communities to develop their economy or have access to healthcare and educational services. This section of the Mozambican coast is dotted with islands, islets and barrier reefs, which makes it a paradise for surfing, diving and fishing, and the reduction in tensions following the end of civil war has allowed for further exploration and studies on the biodiversity of this previously under-estimated region of the Western Indian Ocean.

In 2011, the discovery of gas fields off Mozambique’s coast gave rise to predictions of a transformation of the country’s economy, but also a corresponding impact upon many marine ecosystems. A year later – after a decade of research, CORDIO (Coastal Oceans Research and Development in the Indian Ocean) published a study indicating that the Mozambique Channel is home to the second most diverse coral reefs in the world after researchers found over 400 different species of coral in the region, almost equivalent to the numbers recorded in the Great Barrier Reef and the Andaman Islands. Earlier this year researchers Timothy R. McClanahan and Nyawira A. Muthiga from the Marine Programs of The Wildlife Conservation Society published another study presenting how the reefs of northern Mozambique and the Quirimbas Islands exhibit environmental characteristics that can allow scientists to create a portfolio of examples of climate change adaption. When combining the increased number of coral taxa (a biological group of naturally related organisms) in the deep waters of the south with the thermal stability and lack of extreme temperatures of the sea-surface in the north (which is important for the appearance and persistence of more sensitive species), there’s an environmental heterogeneity that allows for the existence and preservation of many species. Despite the region’s limited potential to expand due to its geological and oceanographic limits on the southern edges, it does have the potential to become its own adaptive centre, should the reefs remain well-managed and not over-explored or exploited. These circumstances have given rise to the moniker “reefs of hope”, as many of the species seem to be unaffected by the variations in sea-surface temperatures seen elsewhere around the globe (a catalyst for corals to expel the symbiotic algae that provide them with the incredible hues and nutrients and which results in the bleaching of entire populations of corals).

Coral reefs are important within global and marine ecosystems providing habitats, food sources, acting as a buffer for coastlines to protect them from storms, and as a source of income to local communities in the form of tourism and recreation. Needless to say, they are also of importance to surfers as the setting for many high-quality waves. But reefs worldwide are under threat from a host of sources, including warming sea surface temperatures, ocean acidification, pollution by chemicals, nutrients and sediment, ultraviolet light, invasion by alien (non-local) species and the habitat destruction caused by unsustainable fishing techniques, divers, boat anchors, coral collection or mining and dredging. Many point their fingers at overfishing and other human-factors as the main reasons behind the degradation of coral ecosystems though – reduced numbers of fish species means more sea urchins and algae growth that damage and suffocate corals if not controlled by predators. The McClanahan & Muthiga study showed however that climate disturbances around the northern Mozambique Quirimbas region had more negative impacts than human influences did, as variability in coral benthic cover and taxa was relatively high in reefs near urban areas suggesting that there are a number of environmental forces that have a greater affect on coral communities. Still, the moderate levels of fish biomass measured in the research, together with low compliance on management in and out of restricted areas, indicate widespread fishing which in turn will hinder the region’s potential to adapt to climate changes.

Both the analysis and the results of this research shows just how fascinating the underwater world is, and how nature has its ways of maintaining an equilibrium through constant adaptations.

Whilst Mozambique is neither a mainstream surf destination nor it’s reefs a regular topic of conversation, the discovery of such versatile coral communities may very well turn the eyes of the world to this forgotten stretch of Africa’s coast in the near future. Hopefully the management of these areas will improve with time and the coral species found there will be able to prosper, continuing to provide us with mind-blowing colours and impeccable reefs over which to get barrelled.

Our thanks to photographer Joel Sharpe for allowing us to share his underwater reef images.