Guest Blogs, TravelKamaka: 23° South by 134° West

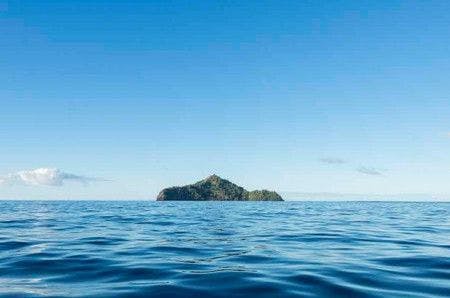

1500km south east of Tahiti, and 6000km south west of the Americas, the Gambier Archipelago could definitely be mentioned in the Collins dictionary as a definition of “isolated”. These islands are not a common surf destination; or even a common destination. With less than a thousand inhabitants the capital Mangareva receives most of its tourists during their two weeks of festivities in July, and for the rest of the year the only unusual faces to walk the streets are those who have arrived by sailboat, usually just passing by on the way to Tahiti. There’s no problem revealing the exact coordinates of these islands lost in the Pacific since, well, they’re lost in the Pacific. Among them Kamaka is the first mentioned by the locals when talking about surfing. “It’s like Teahupoo”, they say, with their eyes open wide. Not many there surf, but I believe that if they did then they’d be happy to share their waves with foreigners, since everyone we met gave us a bunch of bananas or a bag full of papayas; and the words “generosity” and “friendship” seem to be taught to babies before “mom” or “dad” around here.

The archipelago is partially surrounded by coral platforms that come close enough to the surface to cause a barrier effect, soothing the currents that come blasting from the deep ocean and protecting the islands, giving the sensation of a being in a huge swimming pool. There are two ways of getting to this “ocean lagoon”: breaking your piggy bank (which must be overflowing) and buying a plane ticket to Tahiti, followed by one to Mangareva (flights are inconsistent and expensive); or coming by sea, in some sort of vessel depending on your motivation and detachment. Due to a series of “fortunate accidents” (and of course, with my piggy bank being far away from overflowing) I ended up taking the apparently more interesting and definitely more demanding option: sailing. A while ago, in a badly connected skype conversation with my friend Josh Knox (who I had met a year before), I managed to pick out the words “sailing from Panama to French Polynesia, are you in?” This proposal made me quit the easy going life and consistent perfection of the sandbanks in Puerto Escondido- Mexico, and hop on five different buses straight to Panama, getting to Bocas del Toro four days later tired, smelly and ready to begin our trip. Four intense months later, we finally arrived.

On board Kuhela (a Down East 38′ made in California in 1979), in the middle of the ocean, I saw the other side of the coin. The tranquillity that I thought I would find gave way to hard work and 24 nights of broken sleep, until it returned upon sighting land on the morning of the 25th day. It was 579 hours between Galapagos and the Gambiers: enough time to read one or two books and to understand how small and helpless we are in comparison to nature. After spending a week in the paradise that we had sought, mostly stuck inside the boat trying to fix some apparently irreparable issue with the engine, we ended up solving the problem with the easier yet slower solution: ordering a new part. Until the 2kg brass ring arrived we were stuck there, which in reality was a lot better than it sounded. Our engine problems allowed us to take a deep breath, fill up the dinghy, and explore other pieces of land in this vast lagoon in search of something that resembled a wave and coral reefs where we could freedive.

We set out without a defined route but with a deadline to get return, since Josh had a call set up for 2pm with the agent in charge of sending us the damn part needed to repair our engine. For that reason we only took the snorkelling gear, thinking that we wouldn’t have time to surf even if we found something; it was a rookie error. As soon as we left the bay in which we were anchored, pulsing movements in the water were noticeable and we could see white lines on the horizon from waves breaking on the barrier reef. Approaching Makaroi – one of the islands on the Southwest part of the archipelago – we were surprised by the intensity with which the waves crashed on the North coast. With the dinghy in neutral we sat and watched as the swell entered the bay, wrapped around the island’s rocky corner, and formed confused waves when hitting the reef which after a few meters organized their lines and transformed into a walled up, fast, face that soon disappeared when the reef dropped away from the ocean’s surface. It was a wave, and it was surfable. In disbelief and a bit frustrated at not bringing our boards, we kept going another 2km further south towards the famous Kamaka.

Unfortunately (or maybe fortunately) we didn’t come across anything like Teahupoo, but what we saw was surely enough to raise our collective heartbeats and increase our thirst for a surf, having spent almost a month at sea without even jumping in the water. What caught our attention the most, after the obvious image of the 2m turquoise-blue lines running parallel to the coast, was the contrast in the location’s vegetation: pine trees and palm trees balanced side by side, from the beach up to the highest peak on the island. Black volcanic rocks covered the surroundings, while at the beach “beach rocks” looked like they had been placed there by someone – although we later found out that they’re actually formed by a chemical reaction between sand and salt water. The place was strangely intriguing, and the transparency of the water was calming whilst at the same time it frightened us every time coral heads became visible just below the surface. Board-less and with no time to go back and get them, we pulled our hair out with every set that came through. Confronted by the proof that there were rideable waves, all that was left was for us to hit the gas and find a place to freedive in an attempt to keep ourselves busy, hoping that the day would pass quickly so that we could come back the next morning.

The smell of Costa Rican coffee and over-ripe papaya being cut open signalled a new day in the darkness before dawn. With our bodies stiff and our minds lingering between two dimensions, we slowly started getting things ready and throwing everything into the dinghy, which floated patiently beside Kuhela. As the once full coffee pot started emptying, we ramped up the pace as though we were under the pressure of a hourglass, although in reality it was simply the effect of the caffeine. The distance between Mangareva and Kamaka is just 15km, which is not normally considered far, however when the dinghy moves at 15km per hour and petrol costs U$2,50 per liter, the perception of distance changes a lot. Checking to make sure that we had food, water and an anchor, we fired the engine, trying to smother the noise with facial expressions out of respect to the people still asleep aboard the boats around us; it was pointless. Halfway there we noticed something different from the day before; white water wasn’t visible near the islands anymore. The swell was definitely still there, even if in a less violent way, and approaching a tidal buoy we saw that the water was at its lowest level.

We became slightly discouraged when motoring past Kamaka’s neighbor, Makaroi, which on the day before had emanated fury with every crash of a wave on its coast but which in that moment seemed as docile as a pony. Soon the offshore breeze blew our discouragement away and brought fresh air and inspiration as we entered the bay at Kamaka to see that the slight drop in the size of the swell, combined with the low tide, had organized the sections and aligned the waves. Right there and then a great lesson was learned: each surfer should bring their own block of wax in order to avoid wasting time bartering with one another or playing rock-paper-scissors. The anxiety caused by the vision of those almost perfect waves eased when we jumped off the dinghy and dove into the refreshing and crystal clear Pacific. Surfacing with a smile spread across our faces, we paddled towards the outside, towards our reward after almost a month at sea being conscious victims of the power of the ocean: “when you seek, you find”, I thought to myself.

From somewhere in the Pacific the swell travels through waters as deep as 1000m, and over a very short distance and time this number shrinks until it gets to the 3m deep barrier reef that irregularly circles the Archipelago. Soon, the water begins to darken again, and the same swell settles when the depth reaches 30m, until it’s abruptly interrupted again by this reef platform that surrounds the north west coast of Kamaka that gets as shallow as 1.5m, forming a sharp lefthander that runs along the volcanic rock coast. The wave fattens out a few meters after take off and then reforms when it hits the shallower parts of the reef, before fading away completely on the beach. For this south west swell the waves came in constant intervals, but were tricky to read and therefore positioning was key. Trying to sit right on the peak meant possibly getting a set on the head if a particular wave missed or decided not to wrap around the point, causing the wall to run wider and close out faster; there is a price to pay for everything. We spent quite a while watching the waves, and in that first session of the day the inside seemed to provide the richest pickings as the waves reformed with less size and power but walled up enough to make your heart beat faster when racing down the line with a clear vision of the coral heads just below the surface. Just as we began to believe that we had found a completely isolated surf spot, with almost perfect fun lefts and no sign of another human being, we spotted a canoe on the beach. The next things to enter the scene were a man and his dog, walking up the hill along a trail between the trees that had clearly been cleared by someone. Suddenly, we came back to our senses from that state of trance. As soon as our arms started begging for mercy we paddled over to the beach to check out the island and see who lived in that previously seemingly uninhabited place.

The way that some things unfold is magical. Sitting on top of the hill, drinking coffee with the man that we had seen walking earlier, we realized that he was in fact the same person who we had heard about some three months ago in Panama whilst listening to our mate’s story about this high quality wave in the Gambier Archipelago. Apparently a friend of his had found some sick barrels with no one out, and after surfing used to have a couple of beers with the only local. John – the son of American/Tahitian parents and born in Tahiti – moved to Kamaka more than 30 years ago and has lived here ever since. He built a house and raised two children on this island that doesn’t even appear on most maps; which according to him never proved a problem when trying to find tutors for his kids. He didn’t lack stories, and while waiting for the tide to come in we sat under a pine tree and listened to his adventures.

Intense sounds coming from the sea made us look down, and seeing the swell entering the bay with renewed vigour we thanked John for the coffee and ran down for a second round. The waves were breaking closer to the rocks and deeper on the reef, attempting to prove why the place is called “mini Teahupoo” by the locals. More water and confused currents made it clear that it wasn’t a good idea to be hanging around near the impact zone. The afternoon session seemed more intense and more fun than the morning. With the high tide covering the reef by a few extra centimeters our confidence grew, motivating us to catch the wave behind the peak and take off late, enjoying the inclination of the wall before a brief fill and reform on the inside. With our shoulders almost immobile and our eyes burning from looking at things underwater, we reluctantly paddled back to the dinghy which was still sat exactly where we had anchored it. The anchor weighed more than my body had the energy to lift, and the unstoppable laughter when we understood the ridiculousness of the situation didn’t help me to haul it on board. We had spent the day on an almost deserted island surfing waves that in our eyes were perfect, until our bodies said enough is enough. An air of “mission accomplished” gently feathered the lips of the waves still running, uninterrupted, all the way to the white sand.

On the way back our eyes were still catching glimpses of the blue lines left behind, while our minds tried to control the turbulence coming from our stomachs, especially after John told us about his son’s (Teotu) pizza place in town. An idea was born, and it became a mantra. It was only when taking the first bite of that slice of heaven covered in cheese that the true sensation of mission accomplished was revealed. And when life seems as though it can’t get any better, Teotu carried out one of his creations, the Kamaka:

“That’s on the house.”