Interviews, Surf cultureDrawing Everything Out Of Nothing

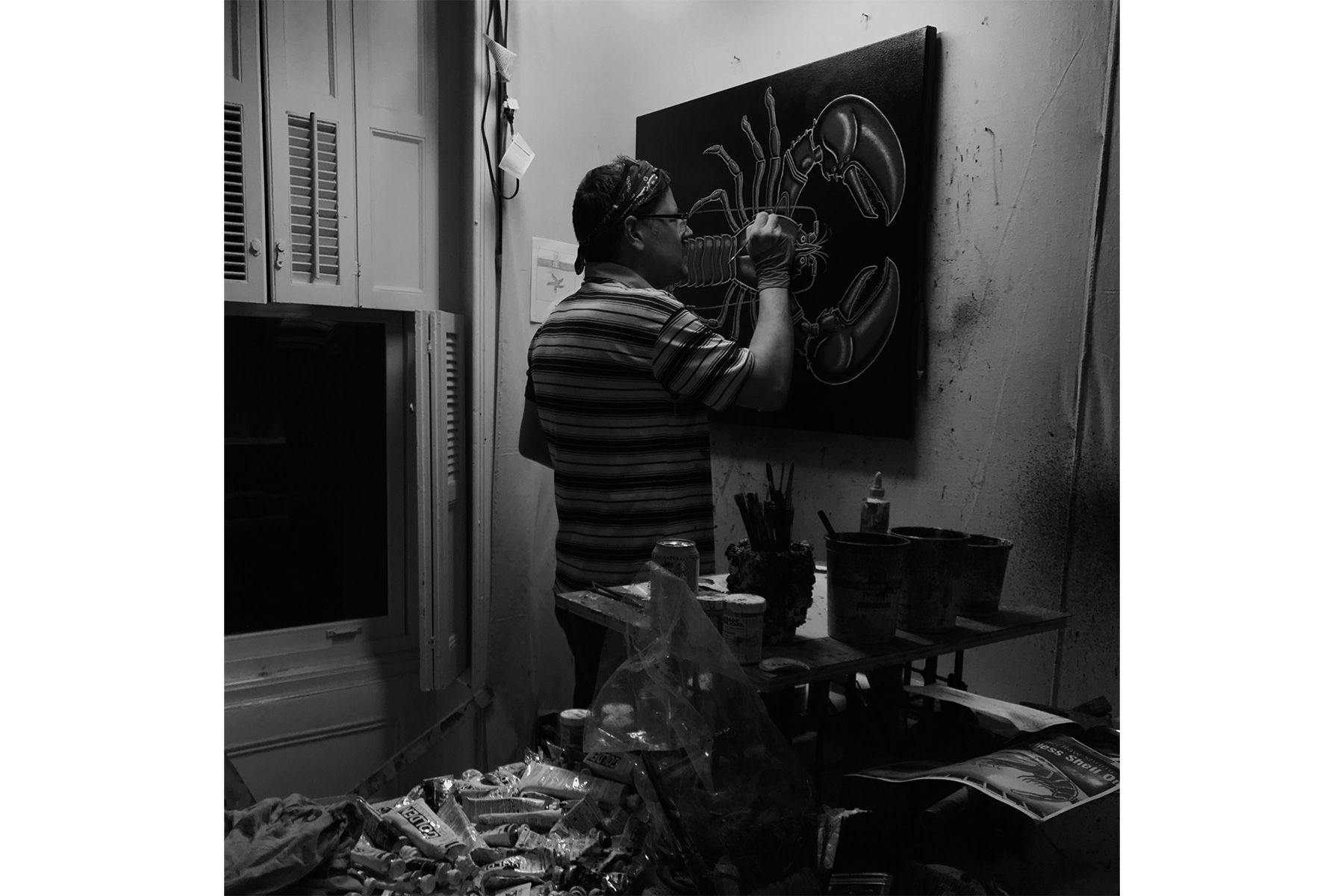

Matthew F Fisher and The Magic of The Ocean’s Unknown

Brooklyn-based artist, Matthew F Fisher may not be able to surf a wave, but he surely knows how to paint one. Evoking sea memories and placing them alongside random discoveries and ongoing curiosities, Matthew depicts an environment ever familiar to surfers from a perspective so unique that perhaps only someone who doesn’t surf could find it.

Born in Boston and spending a large portion of his youth at his grandfather’s beach house in West Hampton, Matthew was constantly surrounded by the breeze of the Atlantic Ocean and the soundtrack of the surf. These early memories sparked what he defines as “a fascination with the magic of the ocean’s unknown,” eventually laying the foundations for his work as an artist.

Matthew’s most recent show, The Sameness of Every Day, runs in online format on Taymour Grahne’s website until 22 May, 2020, featuring a selection of small drawings and paintings that give but a taste of his work. Surf Simply reached out to Matthew to find out more about his artistic journey, what his waves are made of, and the ins and outs of his creative process.

Matt, when do you know a painting is done?

Ha! For me, it’s done when it’s done. I am a process based painter: have to do this, then this, often working from furthest point back forward. I start each work with a spark of interest, from a simple bend in a line to what would happen if the bird’s wings went from the top of the canvas to the bottom? After that, I just paint. Still, there are works that need to change as I work them, a little voice chirps in my head and I follow that voice. I need to be surprised by my own work, and this is how I keep that going.

Can you mention some of the main events, people, and reasons that led you to start painting and then want to become an artist?

Art was the only thing I was good at. My parents have been, and continue to be, extremely supportive of this. As a child, we often took day trips to the Art Institute of Chicago to look at art. I have a strong memory of seeing the Ed Paskche and Rene Magerite retrospectives in the 1980s. Both taught me the importance of the painted image, craft, and narrative in their own ways. Also, how images can be shocking, challenging, and humorous while being completely serious. In college, I was drawn mostly to the artists that professors couldn’t explain to me: AR Penck, Roger Brown, Roy DeForest, Kenneth Noland, on and on. I enjoyed the challenge these artists provided to the educated viewer and I looked to them for inspiration.

After receiving a BFA from Columbus College of Art and Design and an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University, you spent nearly nine years painting highly detailed, politically-oriented French military outfits before shifting to renderings of the marine and coastal environment – which has remained a ubiquitous, if not the sole central theme of your work since 2011. How and why did this transition occur?

Honestly, I was tired of painting from reference books. Throughout those soldier paintings, I had a book in my left hand. The internet is way too vast to find something specific of interest. With books, many of which were found on the streets, I could flip through a chapter about monkeys and find an exact species that I was interested in, or whose pose worked with my painting. An internet search for “monkeys” is like yelling into the wind – too much information comes back. Having worked like this from 2003ish to 2011, I needed to walk away. I wasn’t sure what was next, but I knew I didn’t like painting while always holding a book. I spent six months making all sorts of paintings trying to figure out my next thing. I remember one morning, walking into the studio and saying to myself I was “going to do a drawing of nothing”. Whatever that meant? I had no idea. But as I thought about it, I drew a straight line, sun, sand, and some beach grass. It was then that I saw that nothing could be everything.

And I imagine that at some point you began to feel like your work was making (more) sense to you, like you were finding your “voice”?

I was fortunate to go to school when there were no real expectations placed on me. I might have missed this window, but it seemed the goal was to graduate, get a teaching job, and teach others how to do that. I powered through art school in 6 years, getting my MFA before I turned 24. I had no knowledge how to teach students, as I had just finished school myself. During my two years at VCU, I made every painting I never want to make again. I joke, but it is more truth than humor, that I am self-taught since 2000. I definitely learned a lot about making art in school, but I didn’t learn about what art was. I had to find that out by myself, with some help from friends such as Holly Coulis, Ridley Howard, and Jim Lee among others. It was nice to have a strong nucleus of artists during those early years. My voice came when I asked myself what I wanted to paint? That was somewhere in 2002, my answer was “thrift store” realism. I chased that goal.

Even though you’re not a surfer, your work surely alludes to the fact that you have spent quite some time observing waves and the ocean. What have you learned from these observations?

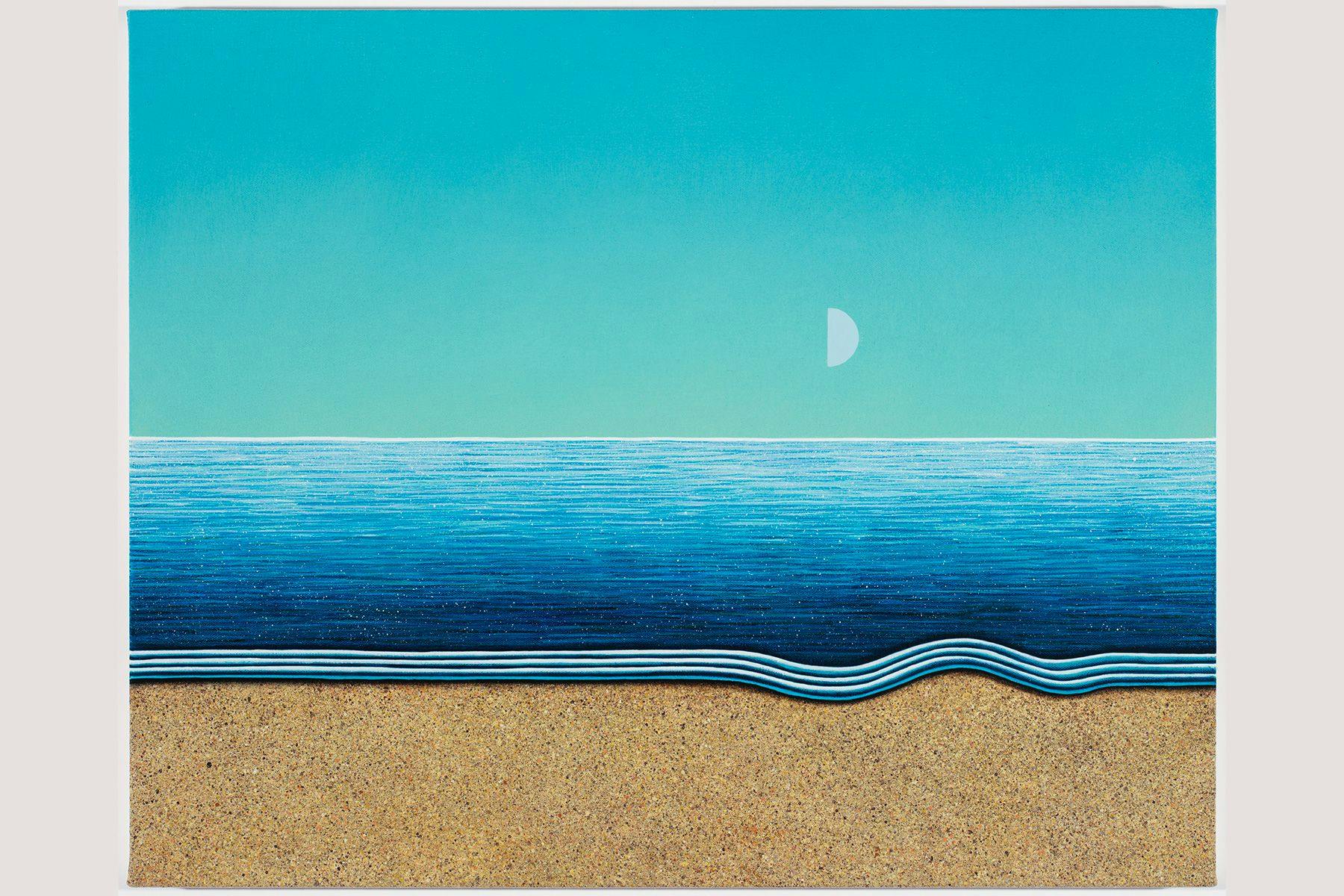

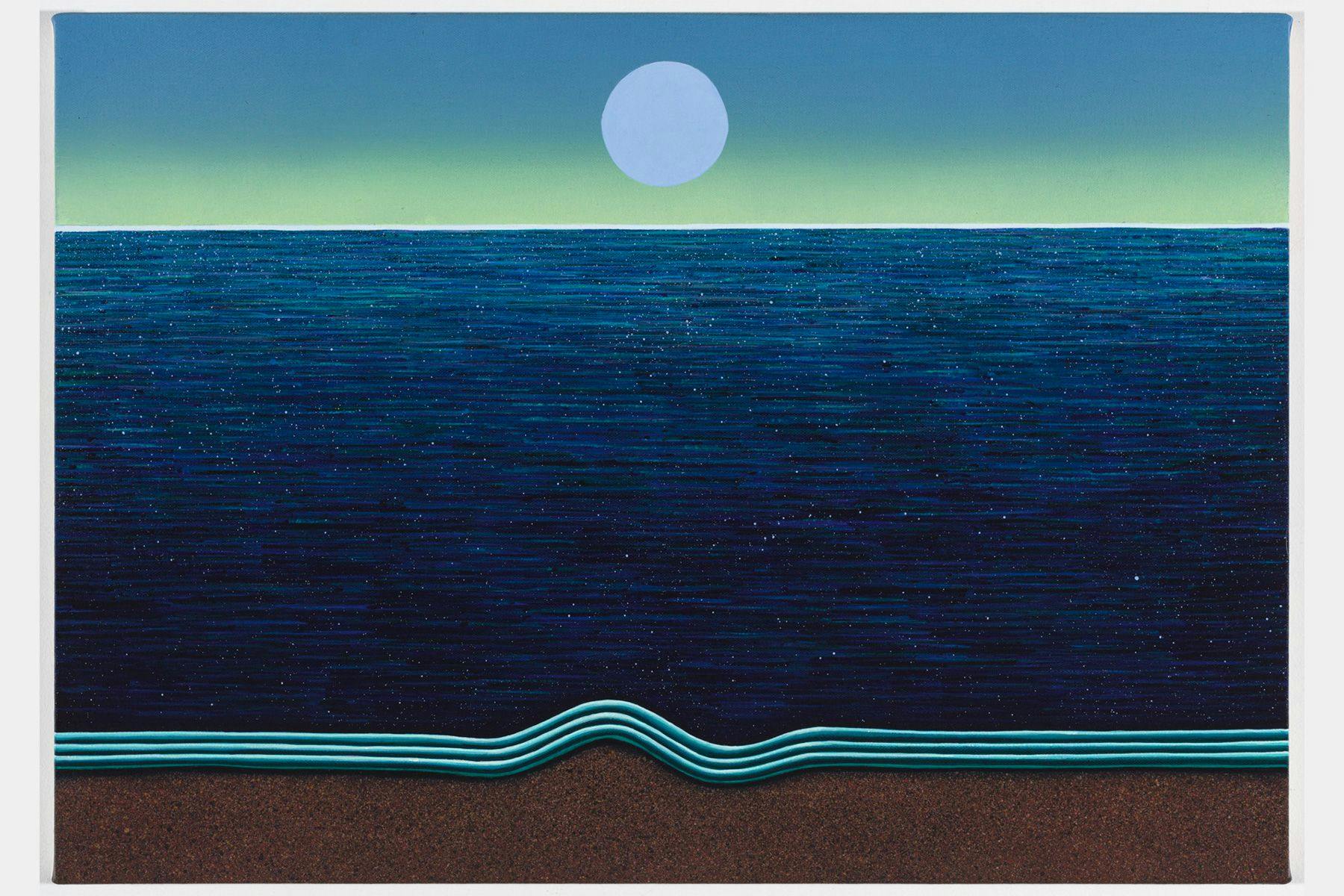

I spent my summers at my grandfather’s beach house on Long Island. It was a simple shack, only three rooms, but twenty feet from the ocean. It was also elevated on stilts, which made you feel like you were floating in space or a treehouse. I remember going to bed and waking up to the sound of surf crashing and how cool that was. What I learned from that was that observation builds memories. In a way, my paintings exist within the reality of one’s memories. When we think of a particular wave, rarely do we recall an exact wave. Just like sunsets, rocks, and seagulls. Instead, our minds summon a collection of waves and create a facsimile of what waves are. My images are not real; rather, they are idealistic representations of what we thought we saw. In that sense, everything is real.

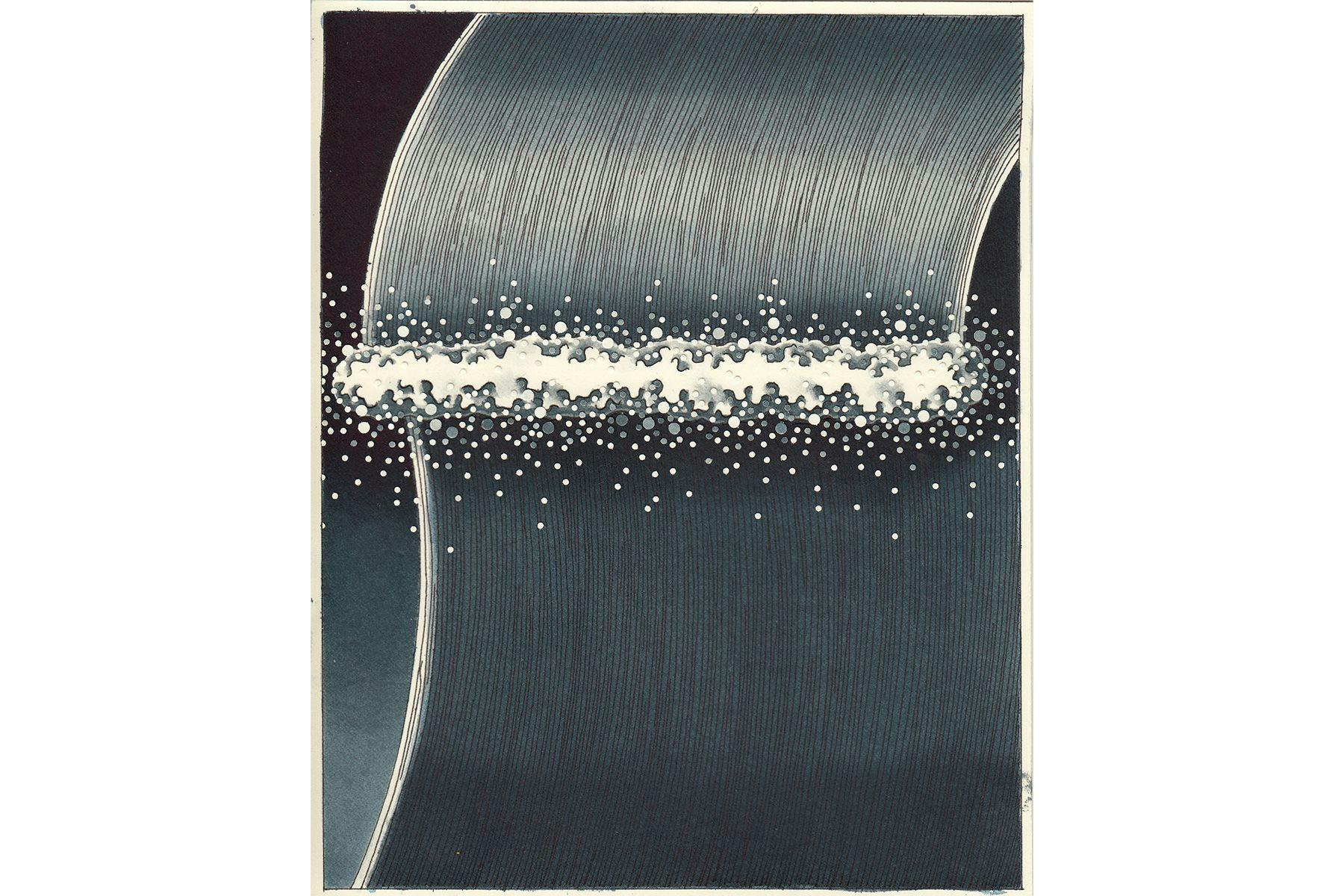

At first glance, your paintings strike me as very simple and light, probably due to how few elements are there and their composition. After a second look, however, I discovered a richness of details, all of which made more sense when I read about how you use several layers of different-shaded dots to paint the sand, for example.

I was trained in the darkroom before the brush. Taking pictures on my old SLR 35mm trained my eye to constantly frame the world. I am always conscious of the four edges of the frame. When printing in the darkroom, we were taught to dodge and burn, make your “shadows have shadows”. I bring this sense of composition and detail to the paintings. There’s a richness in this slow build up that can only result from how I paint. This density of layers creates a heaviness that is uniquely East Coast [of the USA]. Think of Minimalism, New York gave us Serra, Andre, and Judd, all who made work that was so physically heavy. Out west, Irwin, Turell, whose work was light (pun intended). Even though I paint fleeting moments of crashing waves or things we truly can’t see, outer space, I enjoy this idea of existence. That what you see is due to the fact that you are right here, right now. And I build the paintings up like re-living a memory, each time it is slightly different and recorded as such.

You have said that being a parent has forced you to make the most of your time both in and out of the studio. This reminded me of how Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard remarked that he had never written as much as after he became a father. From that, I have two questions. First: Apart from time management, how has parenthood influenced your creative process and/or your art in general?

No time for grab ass. When you have time in the studio, you have to make the most of it. I have also become a master of knowing how much I can get done with this time. You pace yourself and understand that for now, you are going to be less productive overall. But as the little one grows older, there’re new magical moments. I remember last summer when he walked into the studio and asked me “what is that?” I told him it was a crab and fish (The Mystic Hand, 2019). He looked at the painting for what felt like minutes, and turned to me and said, “I like that” before walking out. It was an incredible moment for me in that my work spoke to a three year-old. I also had a work that had been in progress for close to three years, kicked to the corner of the studio. He said the same thing about that painting, I knew I had to finish it (In the Midst of the Masses, 2019). I can also now ask him what I should paint and enjoy watching him freely draw. Recently he even made drawings after my paintings. I finished a suite of four drawings last week, and let him draw on the backs of a few. Making art is a marker in time, and I like embracing that with my son.

Second: In a profession where you are “both master and slave,” as Henry Miller once put, how do you deal with discipline, deadlines, and schedules?

You keep a sharp memory, understand your own pace, and know it will get done.

In 2017, you moved from New York to LA, where you spent a couple of years, and now you’re back in Brooklyn. How has this transition affected your creative process?

I used to say I don’t paint from life, I make life in the studio. Of course the surroundings have an impact on your studio. Since much of imagery comes from previous experiences, I don’t need to see those motifs everyday to inspire me. And when I am in front of the ocean, it’s much more interesting to take it all in with the plan to revisit that moment later. What I did not expect out of LA, was how important the light is, and how I was influenced by the everyday architecture there.

The light speaks for itself, the sun becomes an extension for your soul – and I am not that type of a person. As for the architecture, I was drawn to what I called the near symmetry of the houses around our neighbourhood of Inglewood. Often, the house was perfectly symmetrical, but then the windows within would be off-centred. I loved this energy of being so close to the perfect, and yet, not. I was surprised when I saw that my 2019 show at Ochi Projects that contained almost all of the paintings I made while in LA, how much this near symmetry was being used in the work from that time: sunsets, rocks, flowers, and waves.

In one of your interviews, you have mentioned that you’re intrigued by the idea of chance learning, or as you call it, ‘found knowledge’, and how you often use old dictionaries and encyclopaedias to title your paintings, going as far as naming an exhibition (Soft Nature) after a toilet paper brand. This strikes me not only as fun and funny but as a highly instinctive modus operandi. In your opinion, what is the role of fun, humour, and instinct in art?

Art is the door that the viewer can walk through. For me, humor is the welcoming mat. I don’t paint inherently funny images, but often the structure of the object painting or the impossibility of it, is where the humor is. I think of my rock paintings – I struggled for weeks trying to figure out how the ripples should wrap around the rock at the edges. Do I show “perspective” space, does the ripple work its way up the canvas, and if so, would that tell the viewer the depth of the rock? I started those paintings as a way to push the image of the landscape to the edge of the canvas. Thus, creating a painting that is entirely about the void of the rock. In thinking of that, it seemed that the ripples had to immediately wrap around the rock. If you break that down, the rock itself has to be paper thin, like a fax machine or those great Ellswroth Kelly iron sculptures of shapes. The impossibility of this makes me laugh. But that impossibility is also the realness of the image.

To come back to seascapes…what keeps you coming back to seascapes?

The unknown. What’s below? What’s over the horizon line? Land. Sea. It’s a mystery as old as time.

Juxtaposed with waves, calm seas, and sunset skies are often figures of planets, the moon, and even comets, which I imagine to bear a subliminal message, to be symbols of some thing(s)?

Maybe the biggest unknown is the cosmos? I enjoy that power. But I also have strong memories of looking up. The Mystic Hand, the main image was found in a street book, thus I wanted to surround that image with icons of personal meaning. What you see there, Haley’s Comet, Saturn and its rings, and the Southern Cross, are the three observations that allowed me to see the universe from the earth. The man in the moon showed in the paintings in 2016, inspired by a Joseph Yoakum drawing, was a personal reference to our son in utero. It continues to be a reference to him.

You have solo show (The Great Fire) later this year at SHRINE in New York City in which you’ll be expanding this aforementioned curiosity for the cosmos. Is this interest in the cosmos the start of a new body of work? Can we expect to see fewer waves and horizons and more constellations in your paintings?

One of the bigger works for The Great Fire, is a portrait of our solar system. I found the idea in a sketchbook from 2017, and now it felt right. I started it before the world wide pandemic we are in today, but as the reality started to sweep across NYC and America, I realized it was the first time I had painted earth. I quite enjoyed that, painting the Great Lakes, thinking of my parents and where they live. I even painted the Florida Keys, cause why not? This was in the middle of March, and all of a sudden, it all made sense. We, as the world, were one. It’s like our reality crossed over into social media. There will be waves, rocks, sea animals, I continue to expand my motifs. Regarding the solar system, I have a desire to find imagery that is universal/personal and serves as the anchor to my work. That idea, it’s gravitational pull, allows me to bring in new images that relate to what I have seen, to the viewer, and of course, allows me to understand myself better.

To see more of Matthew’s work visit his website or follow him on Instagram.