Health and Wellbeing, TravelDon’t Eat That Fish: About Ciguatera in French Polynesia

In June 2015, I arrived in Mangareva, an isolated island in the equally isolated Gambier Archipelago in French Polynesia, together with my friend and captain Josh Knox aboard his beloved 36ft, 1979 cutter named Kuhela. We’d been at sea for 24 days and 19 hours, but ironically hadn’t been fishing. The line had been cast a few times whilst underway, but apparently our cruise-boat speed didn’t wiggle the bait enough to catch the fishes’ attention. Amidst such irony our desire for fresh fish only increased, and having dropped anchor off a coral reef fringed Polynesian island, we anticipated a forthcoming “fish-overdose”. But again, ironically, that wasn’t the case – and it didn’t take long for us to notice the word ciguatera (under a French Polynesian accent) coming out of the mouths of locals when we enquired about the best places to spearfish. Soon we realised that fishing – a millennia-old tradition and means of subsistence across Polynesia – had become an almost strategic activity and long gone were the days when you could just eat whatever you caught, literally.

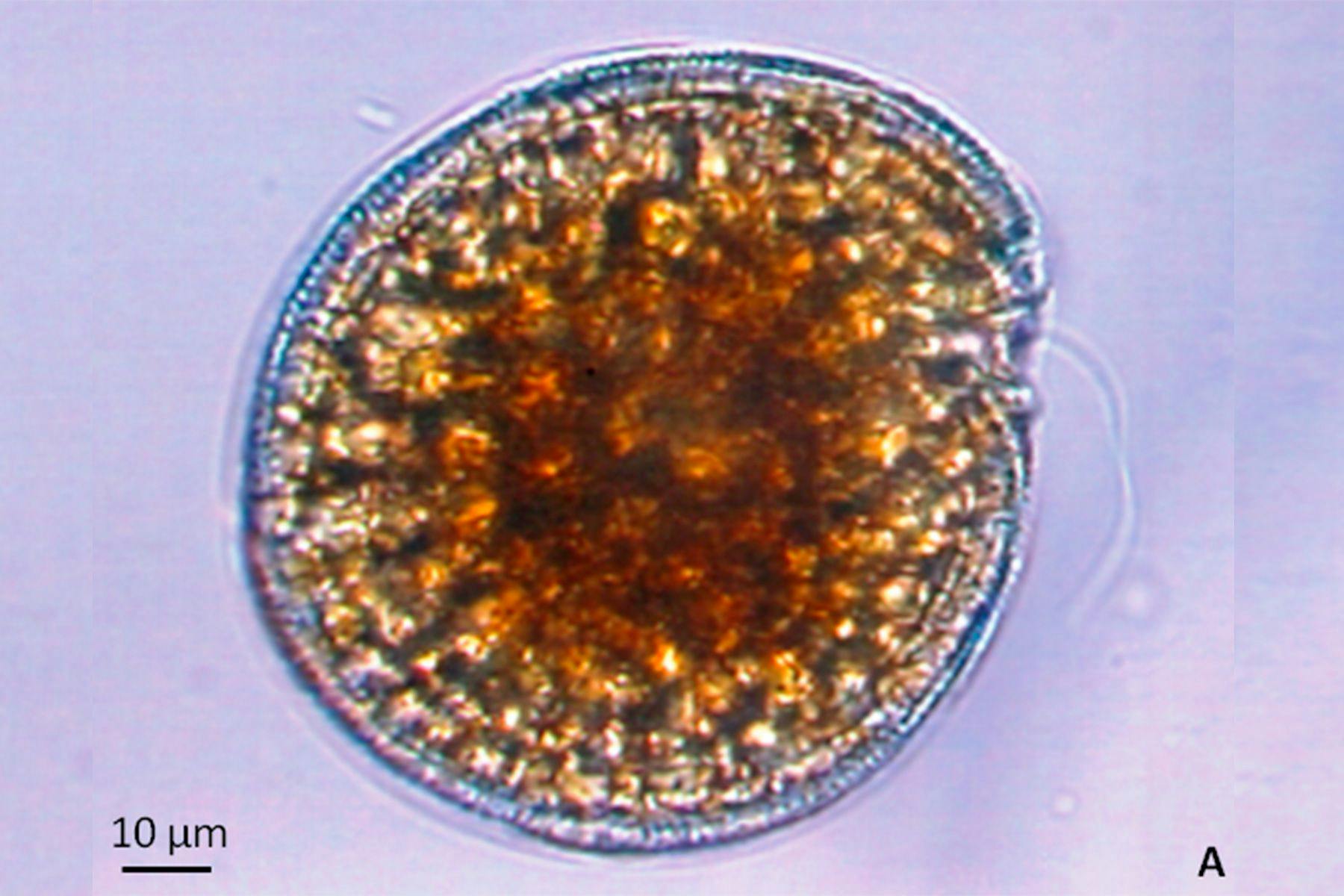

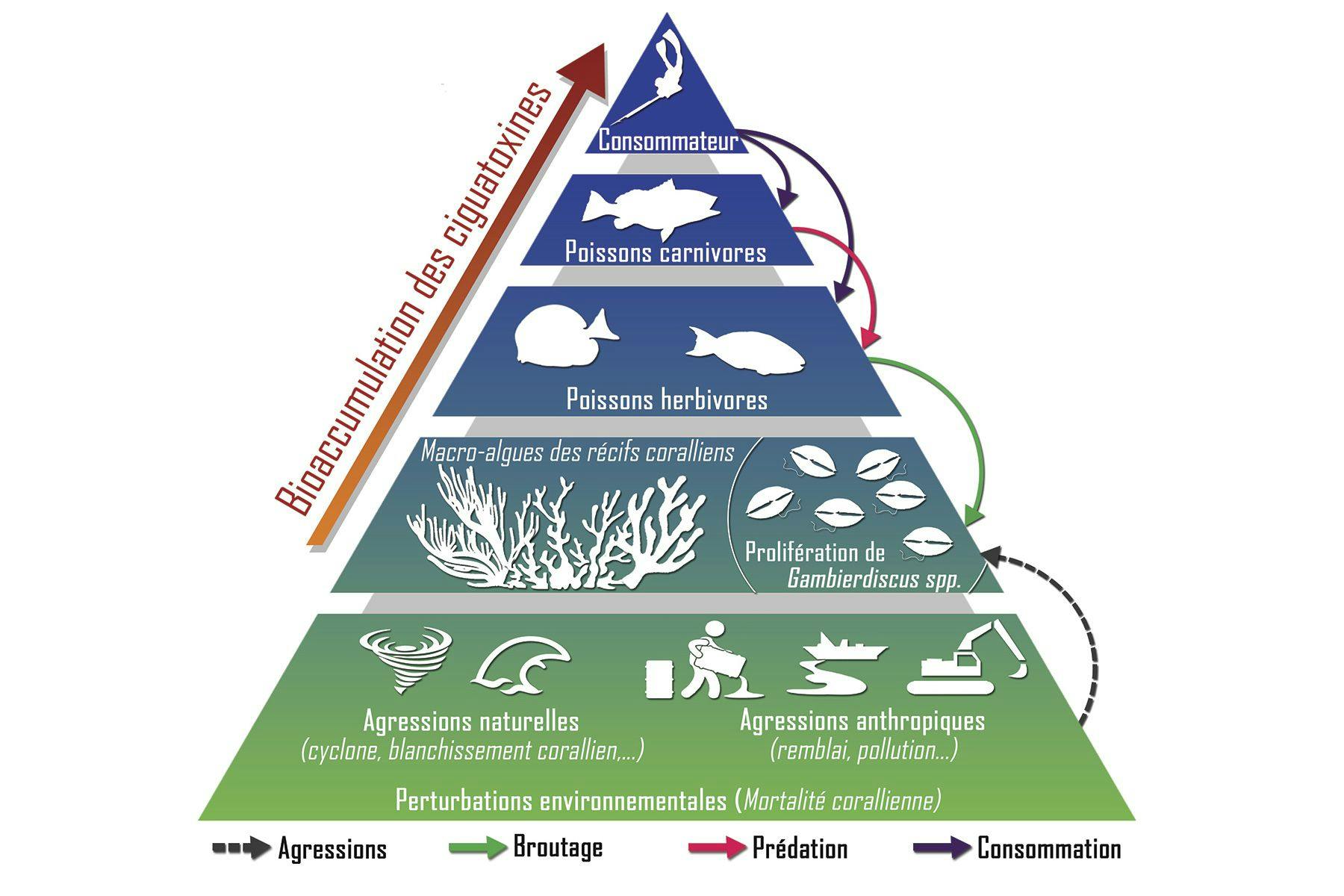

Ciguatera is a foodborne illness caused by the ingestion of (otherwise edible) reef fish which have been naturally contaminated by the ciguatoxin – a toxin produced by dinoflagellates (microalgae) and cyanobacteria, mainly of genre Gambierdiscus. These dinoflagellates adhere to coral, algae and seaweed and are later eaten by bigger fish, who transfer the toxin (via bioaccumulation) up the marine food pyramid. Ciguatoxin-contaminated fish are more common in tropical and subtropical areas (such as the developing Pacific Island Countries and Territories – PICTs) and its consumption may induce a ‘depolarization’ of the nervous system, which has been reported to cause acute neurologic, gastrointestinal and cardiac symptoms (like vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, joint aches, etc), that could last from weeks to months.

A highly dynamic poison, ciguatera can spread endemically or sporadically and its proliferation occurs more easily in highly degraded coral ecosystems, so disturbances like cyclones and coral bleaching – as well as anthropogenic disturbances, such as dredging – are a determinant on the spread of the disease. Although few patterns have been established regarding which specific species are potentially poisonous (making risk management more difficult), the toxin is usually located in the skin, head or roe of reef fish (such as grouper, triggerfish and amberjack) and unfortunately for humans it can’t be destroyed by freezing, cooking or salting. Understanding that this was an issue highly present in the lives of the locals, we also realised it would present a challenge to our stomach’s desires and our means of passing time by spear fishing, as many fish speared within the lagoon or close to the coral’s walls risked being infected.

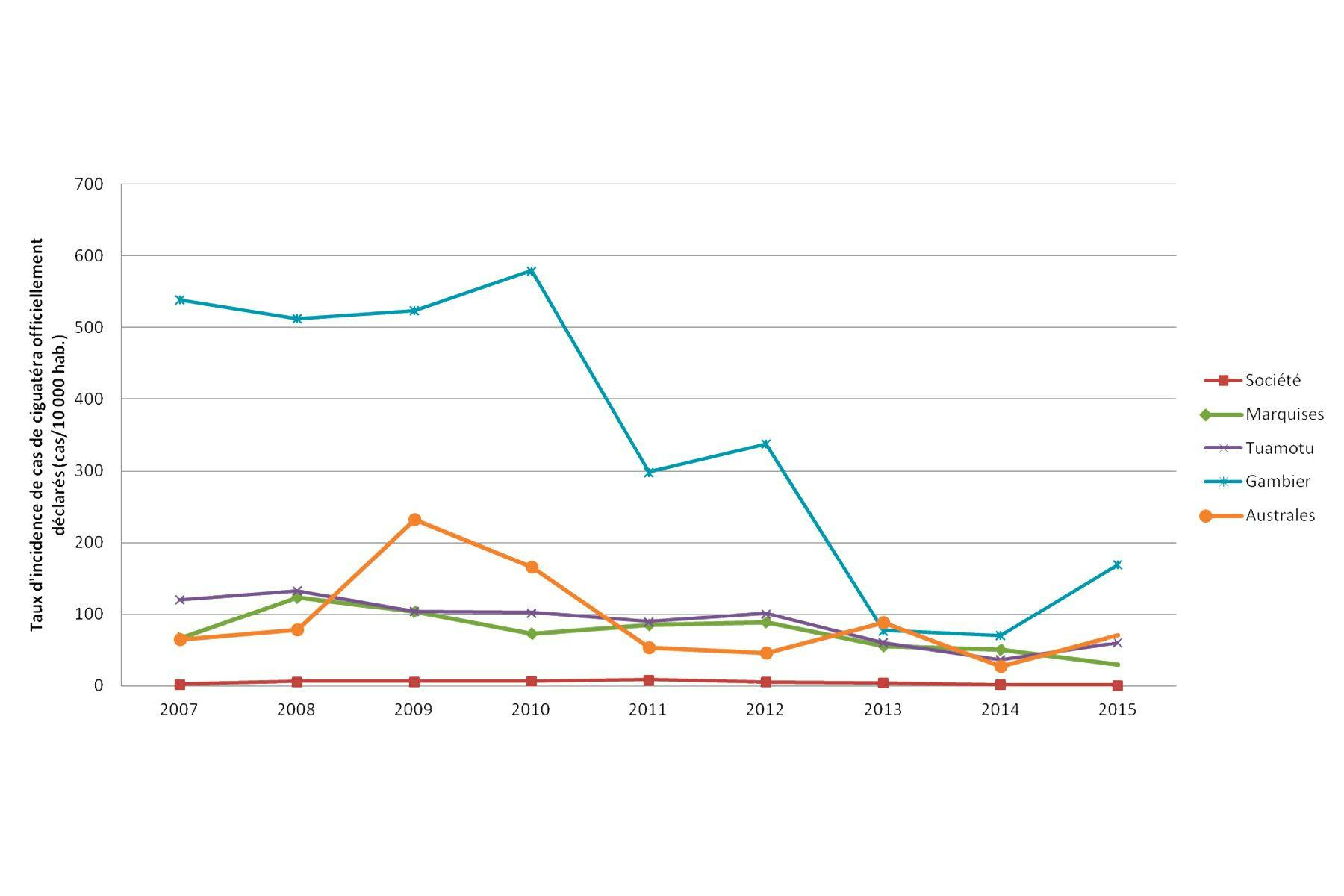

When speaking to locals about the subject, they expressed a continuous concern and clear association between changes in the environment, the increased number of ciguatera cases and the beginning of nuclear testing by the French military at the nearby atoll of Mururoa, in 1966. Such concern is justified by the locals, who cite for example, that from 1971 to 1980, 30-56% of the population of the Gambier Islands suffered annually from ciguatera poisoning. Not only that, but the social changes imposed by the implementation of infrastructure all around French Polynesia for the nuclear tests to take place (the building of shelters, air fields, docks, concrete bunkers, water desalination plants, the arrival of cargo ships and soldiers and the associated culture shock, etc) left clear vestiges in the area and subsequently provided a habitat for ciguatoxin organisms to proliferate, the results which continue to reverberate nowadays through the constant presence of ciguatoxin-contaminated fish.

According to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists published in March, 1990, in a U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Report study, no direct correlation was found between ciguatoxic fish and radioactivity produced by the nuclear explosions. It would perhaps be naïve though, to think that these tests had no impact at all on the marine life, or consequently on the local human population. Many examinations carried out throughout the period of the nuclear tests showed a huge amount of irradiated fish and clams, that were later considered (through medical tests conducted on patients sent to New Zealand) to be the cause of an increase in rates of cancer in Polynesian society. The fact that the French military moved about French Polynesia with ships that had been exposed to radiation dissipated in blasts, assisted in the spread of the toxin, as a species of benthic dinoflagellate is believed to have increased its biogeographical range, caytalysed by human activity, colonising new locations having been transported in ships ballast tanks.

In a different approach, a more indirect impact – through the disturbance of the ecosystem by altering the marine food chain and increasing the potential habitat for Gambierdiscus growth due to blasts –deserves further study, as the disruption of the sensitive ecology of coral reefs is the primary cause of ciguatera outbreaks. Among these disruptions, the environmental consequences of underground nuclear testing include short-term (fracturing of the atoll surface and the triggering of landslides, tidal waves and earthquakes) and long-term (leakage of fission products and transfer of dissolved plutonium into the ocean and food chain) have effects that have long been studied. Such indirect impacts can also be found in a more sociological or anthropological sphere (rather than just on environment or public health), as many locals who’ve suffered from ciguatera need to limit their consumption of fish (usually a basic staple) for several months, which in turn leads to them depending upon more expensive and generally less nourishing imported foodstuffs for their protein intake.

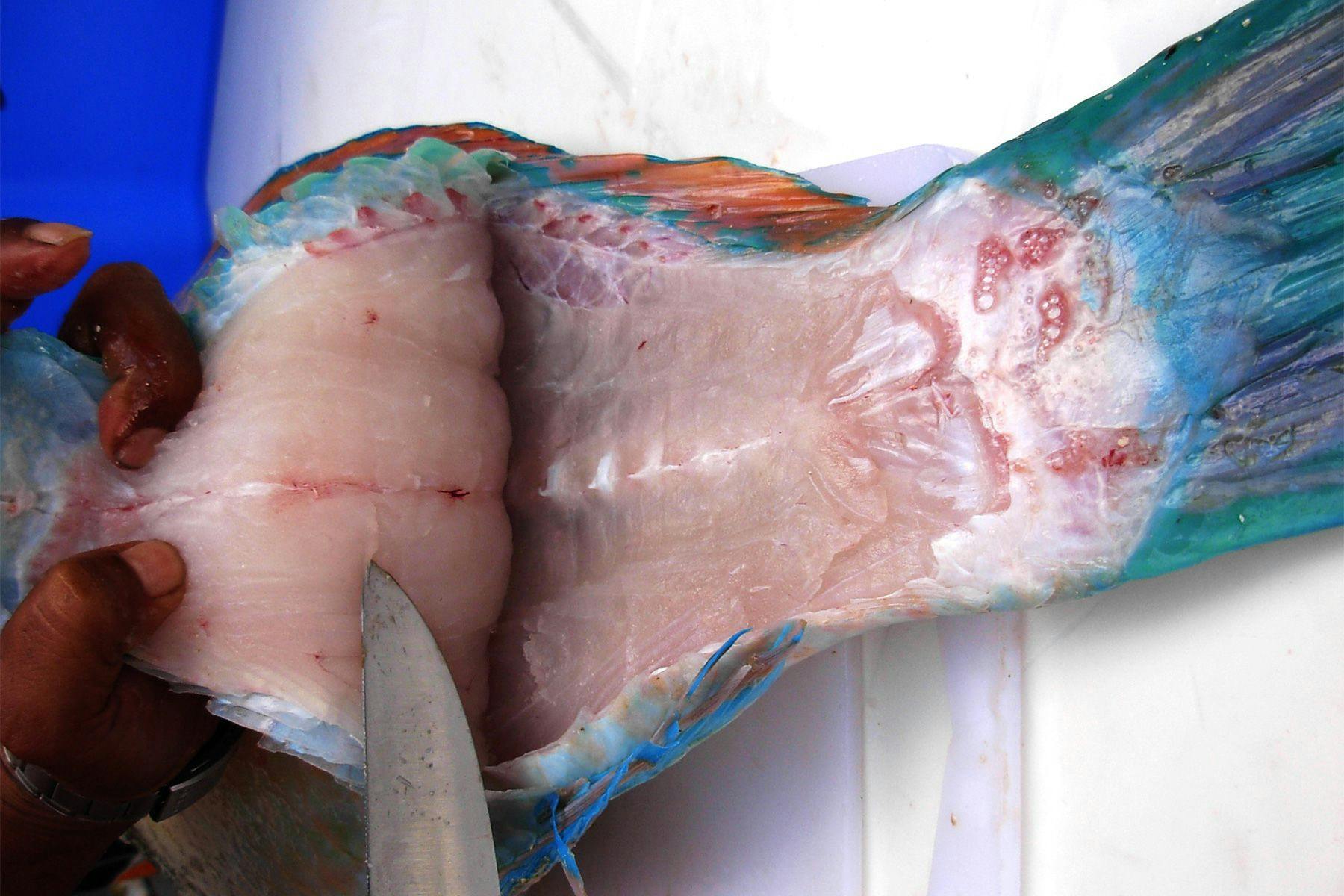

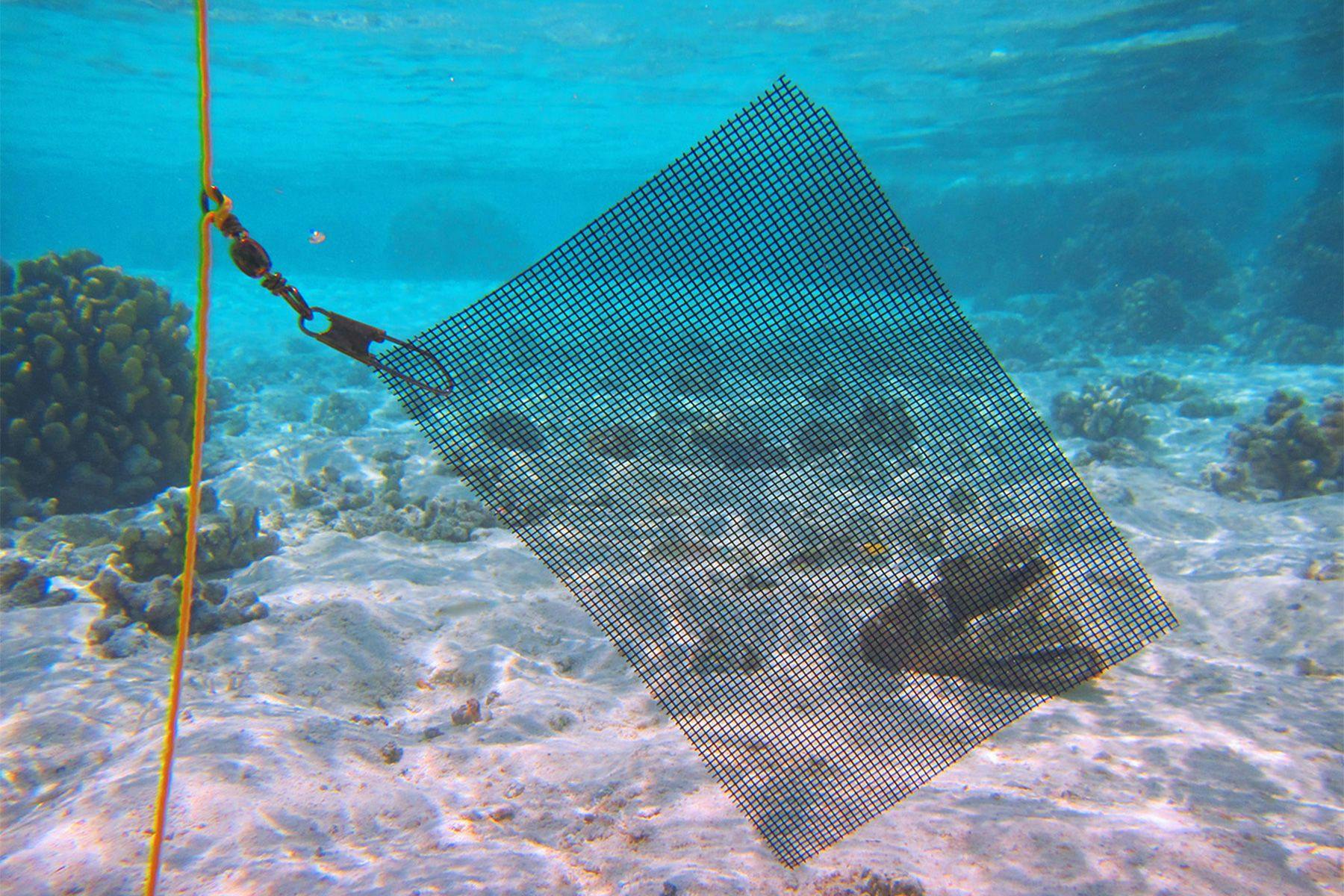

Research programmes by SPC Oceanic Fisheries Programme have conducted several field campaigns to help communities manage the toxic hazards of ciguatera –through mapping ciguatera risk in the affected lagoons and communication and awareness sessions for locals – initiatives which gradually compiled a large database of information on the issue and generated reasonably reliable scientific methods for ciguatera hazard management (such as the “bleeding test”, that can detect the presence of ciguatera with 70% accuracy), that together with the locals’ in-depth knowledge of fishery areas and which species to avoid, significantly reduces their poisoning risk. Still, at present, ciguatoxin can only be accurately detected in specialized labs, and the symptoms associated with the recent consumption of seafood is almost the only basis for diagnosis in humans.

The bleeding test; the specimen above is unlikely to be contaminated with the ciguatera toxin.

The bleeding test; the specimen above is likely to be contaminated with the ciguatera toxin.

It was interesting to witness how -through our major and personal goal of surfing, spearfishing and free-diving our way through French Polynesia – we’d encountered such circumstances that affected the local communities with whom we spent our time, thus indirectly affecting us. Moreover, it was unnerving to witness how a political move dating back to 1966 has had such huge social impact in the colony. The aftermath of these events caused (even if indirectly) a disruption in the marine ecosystem and consequently an increase on cases of ciguatera. The scale of “untouched” information on the subject of ciguatera and the French nuclear testing in French Polynesia is huge and fascinating.

Many surfers dream of a perfect session ending with fresh fish cooked over a beach fire as the sun sets. Yet, we also understand that much as a wave that hits the shore was generated by a storm many miles away, mankind’s actions also have implications that have little regard for distance or time. To experience first-hand such visible consequences in a community on the other side of the globe from where I grew up, and seeing that this dream of a “fresh fish cooked over the fire as the sun sets” is under threat, made me ponder just how long it will be until ciguatera spreads to every shore or reef around the world. In a series of analysis made by NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) on Ciguatera Fish Poisoning in the Pacific Islands, research shows that it is clear how underrated the ciguatera issue is, and how little is being done to manage or prevent it considering that many disturbances that are directly or indirectly related to the subject (like the changes in global climate patterns) are occurring with increasing frequency.

One of the biggest ironies of this irony-laden tale, is that mine and Josh’s greatest motivators for sailing was the freedom and capacity to constantly source our own fresh food through fishing. Instead, we crossed the Pacific Ocean to pay inflated prices for an imported “Catch of the Day” meal in a restaurant. It goes to show that every action has a repercussion, even if half a century later, and 4000 km away.

The author and Surf Simply Magazine would like to thank the Institut Louis Malardéfor their assistance with this article.