Community Projects, Surf cultureDecolonize The Surf

The Ocean as A Contested Space in Californian Surf Culture

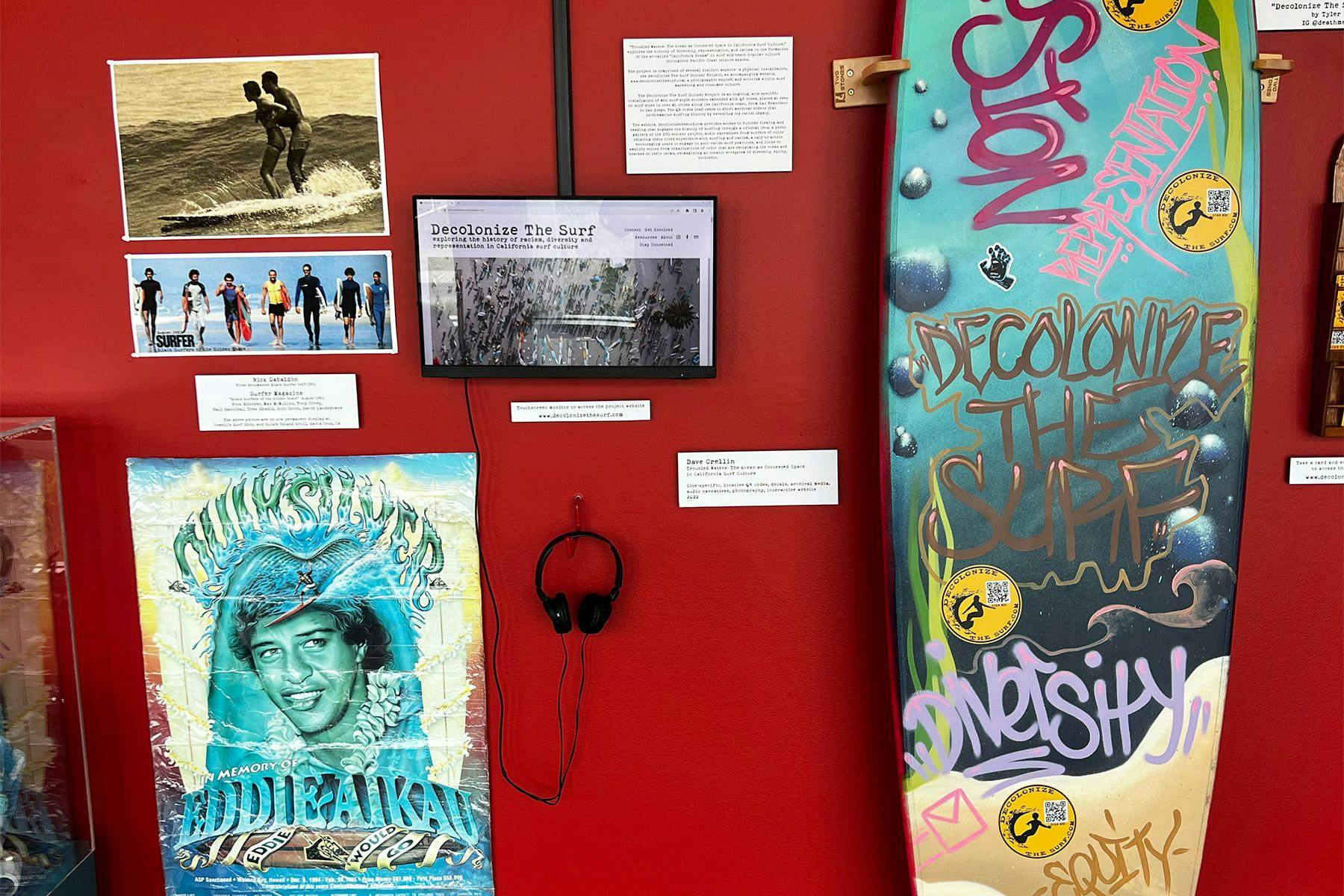

“Surfing presents itself as a locus of physical and spiritual transformation, a realm in which to explore our relationship to the natural world, and a cultural space welcome to all who choose to engage in it, yet is overwhelmingly, unflinchingly, and protectively White,” writes David Crellin in the introduction of his MFA thesis paper in Digital Arts and New Media at University California Santa Cruz. The paper outlines his project, Decolonize The Surf – an interdisciplinary, immersive installation that delves into the history of racism and representation in California surf culture, calling for a move away from the long-standing White supremacy in surf and beach popular culture, towards a framework of greater diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Surf Simply caught up with David to learn more about the project and hear his views on the development of surfing’s socio-cultural landscape.

Decolonize The Surf consists of three aspects: an on-site intervention through QR-code embedded stickers placed at surf spots; a website linking the QR codes to videos, photographs, books, articles and other material; and an art installation. What are you aiming to accomplish with the project? And why this triad?

There are a number of goals or aspirations for the project which are interconnected and in conversation with each other. I grew up in Manhattan Beach, steeped in the dominant narrative of surfing as an unquestioned “White” space which operated as an invisible “program” running in the background informing every aspect of beach and ocean life. I lived a 10-minute bike ride from Bruce’s Beach (the subject of one of the videos on the website), with absolutely no idea of the injustices that transpired there. So, a part of the impetus for the project was becoming aware of my own privileged position growing up as a White kid at the beach, and a curiosity to examine my own silence, complicity, and unconscious bias.

When I began actively researching the history of diversity and representation in surfing, I began to understand the degree to which surf culture has inherited the legacy of racism, exclusion, and White supremacy that is unfortunately a part of the USA’s origin story. I love surf and beach culture, how much it has to offer, and the lessons it has to teach us all. But those lessons are for naught, and the gifts that the ocean has to share are hypocrisies if we don’t take an honest, critical look at our history, and make a commitment to change surf culture so that our coastal leisure spaces are welcoming to all. I want surfing to live up to its potential as a source of transformation, connection, and deep dialogue with the natural world. That can only be accomplished by dismantling racism in surfing, creating diversity, equity, and inclusion in its place.

As to the varying aspects of the project itself, initially I had imagined it to be an art installation in a gallery setting only. At that early stage, one of my professors at UCSC asked me, “who is this project for?”, and that inquiry completely changed the direction of the project. I realized that what I needed to create was first and foremost a conversation, an accountability, and a call-to-action within surfing generally, but specifically for the dominant mode of surf self-identification which is predominantly White (male, and heteronormative). The project had to be something that could reach surfers where they live – in, at, or near the beach and waves. From there, I spent weeks at surf spots looking for inspiration, trying to find a “hook”, and that’s how the surf stickers idea was born. I also realized that I needed them to “do” more than just be a sticker, with an image and a slogan, but function as a portal to the bigger conversation. So, I decided to add QR codes to the stickers, as a way to connect surfers to another level of information, which begins with the series of short videos, and then to the website. The videos are intentionally designed to be brief but powerful interventions – what cognitive scientists call “schema violations”, interruptions into our normal thoughts and routines. The intention is to place a small glitch in the matrix and encourage surfers to investigate further through the website, which is really where the conversation takes place.

The website was created as a place to access information and resources, further one’s understanding of racism and representation in surfing, hear first-hand accounts from surfers of color about their lived experiences, encourage accountability, and to provide opportunities to take action to change surfing for the better. Another crucial part of the website is to amplify the efforts of amazing organizations of color that are building community and helping generations of folk of all ages to feel welcome and get their stoke on in the water. Many groups are also doing critical work to change legislation regarding access to ocean and beach spaces, which have been historically and structurally constructed to exclude communities of color. Every step of the way, I consulted with surfers, creatives, scholars, and activists of color for their input, critique, ideas, advice, etc., to better understand how to shape the project, take appropriate actions as an ally, and stand in solidarity with the collective.

Circling back around to the project in a gallery setting, the installation is an artistic, activist statement, serving as a compliment to the on-site stickers and website, and an alternative opportunity to reach people who might not spend time at the ocean or otherwise access surf culture. It was also created with the idea of evolving it into something that could travel to schools, surf clubs, universities, etc., as a teaching tool and way to get people involved. The dream is to get enough funding to trick out a classic VW van and turn it into a mobile Decolonize The Surf interpretive experience.

You spent nearly two weeks driving between San Francisco and San Diego, placing stickers on street signs, light poles, fences, trash cans, etc., at more than 60 surf breaks in 40 cities. What were some of the observations you made along the way concerning the state of these surf spots and their surf communities?

Every time I travel down the coast of California, I marvel at the breathtaking beauty of this state, and realize how lucky I am to have grown up at the beach and in the ocean here. But I am also very aware that my experience was informed by the color of my skin and all of the benefits of access and privilege that come with it. Our coastal environments are too often contested spaces for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) and are still overwhelmingly White. Time and time again, I stopped at a surf spot, a surf shop, or a café nearby and pretty much everything you see is a representation of White culture advertisements, photos, statues, graphics… all of it. There may be the occasional statue to Duke or a plaque naming the three Hawaiian princes who brought surfing to California (David Kawananakoa, Edward Keli’iahonui, and Jonah Kuhio). But those few acknowledgments to surfers of color, especially to the Hawaiian lineage that created and evolved the modern concept of surfing, are the exception. They are named as instances in surf history that honor an individual; while in the case of Santa Cruz, a short distance from the aforementioned small plaque at Steamer Lane, is an 18-foot tall, bronze statue of an unnamed, phenotypically White surfer, with the inscription “Dedicated to all surfers, past, present and future.” All surfers. Seriously? Surfing’s identification with Whiteness as normal, obvious, and expected is pervasive and deeply problematic. Furthermore, it is unkind, unjust, inaccurate. It renders Whiteness as invisible and unquestioned, erasing the contributions of surfers and innovators not only of color, but any who do not fit the dominating social order. This Whitewashing needs to be acknowledged, deconstructed, and dismantled then reimagined and reconstructed as a more interesting, equitable, inclusive, and contemporary vision of what surfing was and can be.

Thinking about your research and the conversations you’ve had with surfers, what was the most shocking account and/or piece of information you’ve discovered regarding the legacy of racism in surfing? And the most beautiful?

Probably the most shocking – or at least disconcerting – conversations revolved around the disconnect between what I view as the best parts of surfing and being in the water, and the actions of some surfers and beachgoers. For me, being at the beach and immersed in the ocean is a blessing and a lesson in how to live. I am joyful and in awe of the magnitude of the natural world and wonderfully aware of the contingent nature of my existence. So, whenever I encounter surfers who hold actively racist, sexist, xenophobic, and otherwise toxic belief systems, I am convinced they are entirely missing the point, and have learned very little from their time in the water. It’s as if they are there solely to satisfy their egos, extracting value from the ocean with no respect, no stewardship, and no responsibility – hungry ghosts on floating planks. That kind of behavior, in my opinion, is metaphoric form of coastal pollution.

The other thing that stands out (and never ceases to draw my ire), is the idea of “localism.” There is a long history of localism in surfing, which to my mind, is a very troubling and solipsistic concept. First off, local to whom? Certainly not to the people who are indigenous to this land, that were decimated and subjected to genocide by the colonial settler project. Localism is inherently based on a mindset of entitlement, ownership, and privilege, which are also the hallmarks of empire, oppression, and injustice. There are rules in the line-up which can be useful, beneficial, and when communicated with decency, helpful at most any surf spot. But localism has become weaponized as an excuse for bad behavior, and often has been deployed as a cover for racism and White supremacy.

The most beautiful experience in creating this project has been becoming connected to a wide-ranging community of people deeply invested in equity, agency, and solidarity, committed to changing the culture and narrative of surfing to one that is inclusive, welcoming, diverse, and that views our natural environments as spaces to be shared, honored, and cared for. I have deep gratitude for the individuals and organizations that are building dynamic networks of intersectional support and expanded communities of care for people and the environment. They have been incredibly generous with their time, creativity, expertise, and friendship throughout this process. Bearing witness to their example encourages and inspires me to continue to expand and deepen my efforts to do this work and further decolonize the surf.

Along those lines… Why would you say many people are still reluctant to discuss – or even acknowledge – the issue of racism in surfing?

I think there are a variety of reasons. Real talk – some folks are just racist and have very little interest in investigating beyond what they think they know and what they believe they have a right to. But I would say most people, including most surfers, operate under the assumption that surfing is an egalitarian space, a site of personal growth, enjoyment and transformation that is open to anyone. The idea that all you really need is a board, maybe a wetsuit, you jump in the water, spend some time working it out and one day you’re surfing, boom, end of story. And in a very narrow and limited way, that can be true. But because Whiteness is so overrepresented and overdetermined in surfing, my research points to the idea that a lot of surfers don’t investigate beyond their experience or examine how what they view as normal in surf culture may not be what is experienced by historically marginalized groups. Insight into how racism operates in our society requires effort, education, and the willingness to look inward at one’s unconscious bias and indoctrination into the construct of race, and how it damages you and those around you. That is a very uncomfortable place to be in. But it is the only path of understanding that leads to awareness, accountability, action, and change.

When I started to research this project and began to reach out to various people and organizations of color for insight and assistance, I was often fearful that I would say or do the wrong thing, cause harm to someone through my ignorance, or straight up be called a racist. I had to come to terms with those feelings, and allow myself to remain unsure and unsettled. Copping to my own biases, privilege, and silence in the face of injustice were (are) bitter, shameful pills to swallow. But it pales in comparison to the labor expended and the suffering incurred on the part of our historically marginalized brothers and sisters, and it is really important to be in touch with that reality. I do know that the more I “stay with the trouble,” accept that I am going to make mistakes, the more that I listen, learn and commit to action, the more I am willing to risk and put some (White) skin in the game, the greater capacity I develop to be comfortable with being uncomfortable, the more courage and resiliency I have to continue to stand in solidarity against oppression, and the better person and member of our human community I feel I am becoming. It’s a lifetime project.

In the paper, you note how, despite his overt racist attitudes, Miki Dora “was featured on the cover of countless magazines, starring in movies and television shows, enjoying near celebrity status,” and that “though some contemporary surfing publications have re-examined Dora’s racist behavior, his reputation thrives to this day as a legend in surfing history and is still considered by many, the undisputed ‘King of Malibu’.” I’d like to use that as the basis for the next three questions. First: Did you find any other prominent surfers whose behaviours could use re examination?

Miki Dora was just one of the most vivid and reprehensible examples of how society turns a blind eye to racism in favor of centering and celebrating Whiteness in surf history. In my research, I found many other examples of individuals, clubs, groups, and organizations that perpetrated individual acts of animus against people of color, or created exclusionary covenants, membership structures and legal barriers to limit beach and ocean access to Whites only, as well as a host of other racist practices and behaviors. From the deployment of the law of eminent domain used to take Bruce’s Beach from Willa and Charles Bruce in 1924, to the confrontational and often violent actions on the part of the “Lunada Bay Boys” in Palos Verdes, whose members wore blackface and an afro wig when a group of surfers showed up on Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2014. One doesn’t have to look very far to discover a thread of White supremacy and racism running throughout California surf history.

This sportsman-person duality seen in Miki Dora’s case is also common in the world of art; Nobel laureate, Norwegian author, Knut Hamsun – a great writer yet Nazi supporter – being a pertinent example. With that in mind, what would you say is the role of surfers in dismantling racism?

Surfing, like any other popular cultural formation, has its heroes and icons, who in many ways become the “face” of surfing and how it is imagined. That is a position of incredible privilege and responsibility. I’m not saying that those folks didn’t work their ass off to get there. But there are many surfers who could very well rise to those same levels of notoriety and professional achievement but have been precluded by historical, geographical, socio-economic, and hegemonic barriers. Especially in a sport like surfing, younger generations look up to their heroes for social cues, and a sense of what is important and valuable in the culture. If surfers in positions of access and acclaim are willing to speak truth to power and hold the surf community to a higher standard regarding dismantling racism and demanding diversity, equity, and inclusion, they can have a real and lasting impact on surf culture. If they don’t speak out, then one has to wonder if that silence is evidence of their complicity.

What are your thoughts on the relation between the surf industry and media and the perpetuation of racism in surf culture?

Even more pernicious than individual racists like Miki Dora or others, is a culture and system in surfing that keeps silent, and oftentimes, gives cover and support to people like Dora as long as they bolster the status quo and keep the money rolling in. The status quo is always intrinsically tied to capital. The global marketing and sales of surfing and the surfing “lifestyle” is an over 3 billion dollar a year industry and growing at a rate of 3- 4% annually. Market forces shape and dictate representation across all aspects of surfing’s image and identity – apparel, magazines, films, surf shops, the touring circuit, et al, and it is overwhelmingly White, male, and heteronormative. If you don’t think so, pick up a random surf magazine and count how many White people you see, and how many people of color.

Foregrounding Whiteness as the central identity in surfing has been the focus of surf marketing since at least the 1950’s, from Hollywood beach movies to the surf music craze – and that tendency continues to this day. This seemingly endless cycle of social reproduction in surf culture perpetuates racialized, gendered hierarchies, and it damages our social body. For the surf industry to change, it is going to take sustained collective action and pressure from all of us. To quote Frederick Douglass, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” We need to demand that the surf industry evolve into equitable representation across all fronts. And we can do that by making informed choices of who we support with our time, money, and energy.

To circle back to the project… You have connected with several organisations that promote inclusion, diversity, equity and representation in surfing and beach access for people of colour. What were some of the main takeaways from these interactions? And did you come across any relevant data or projects fighting racism in surfing in other parts of the globe?

I’ve had the good fortune to become aware of and connect with numerous groups and individuals that have for years been fighting to dismantle racism and create diversity in the line-up in coastal cities throughout the USA, as well as across many parts of the globe. Indigenous scholars, and activists are adding critical (and often erased) perspectives to the understanding of racism in our coastal environments, as well as groups such as the non-profit organization Native Like Water and the Indigenous Surf Club, which are building strong communities of indigenous surfers. Hawaiian scholars, surfers and activists have always been at the forefront of the movement to decolonize surfing and foreground their indigenous sovereignty. Selema Masekela, surfing commentator, activist, and entrepreneur co-founded Mami Wata, an African-based collective creating mission-driven products designed and made in Africa – apparel, boards, surf gear, art, books, journals and more – created from an African cultural perspective and narrative, which is expanding the idea of what surf lifestyle can look like. They also partner with world leading surf therapy organizations like Waves for Change, and Surfers Not Street Children, which reach thousands of children in Africa, improving their lives, and teaching them to surf. That is just one example that comes to mind. Similar efforts are taking place throughout the world – in other parts of Africa, in Central and South America. It is very inspiring to see the waves of change that are building momentum and becoming unstoppable.

As for the takeaways…Dedication, joy, community, respect, love, commitment, esprit de corps, fellowship, courage, intersectionality, sharing, communication, acceptance, resilience, and so much more! One of the reemerging structural outlooks or patterns I witnessed in the organizations that I have connected with has been one of intentionally building community for surfers of color; a sense of shared labor; open channels of communication; strong emphasis on creating safe spaces to engage, express, heal and enjoy; and solidarity across marginalized groups. From an organizational standpoint, it is incredible to see how groups are creating communities of care in surfing to support, nurture, teach and heal on their terms, redefining what it means to be in the ocean, at the beach or a surfer in the 21st century. As far as challenges go, I think any grassroots or nonprofit organizations continue to find challenges around the financial resources needed to grow and thrive, which is why material support is so critical.

You’re an artist, scholar, and surfer. In your opinion, how can these three areas interconnect to produce broader positive results for surf culture?

These three aspects constitute what I consider to be a foundational approach to how I create work and live life. They form a “Holy Trinity” of methodologies, as it were, which are interdependent and co-reliant, each one incomplete without the other two. As an artist, there is an ineffable and intuitive aspect to creating that requires trusting your instincts and feeling your way through the process, seeking insight into what the work in question needs or “wants” to be. As a scholar, engaging in study and research provides the necessary waypoints of understanding, which enable me to ground myself in reality and chart a course of significance. And being immersed in the ocean situates me in communion with the natural world, reminds me of the symbiotic imperative of existence, and puts me in dialogue with our more-than-human kin. It is my belief that drawing from these three pillars – body, mind and spirit, or creativity, intellect, and intuition, if that registers better for some – gives us a more complete vantage point from which to participate in the world, especially as regards issues of co-existence, justice, stewardship, and ethical behavior. To that end, I think surfers and surf culture could greatly benefit from actively incorporating the above in equal measure to evolve the contemporary landscape of surfing.

How do you see the issue of racism in Californian surf culture changing in the future?

I see some very positive and meaningful changes already happening throughout all sections of surf culture. As I mentioned, BIPOC surfers and their allies have been reclaiming their rightful place in coastal leisure spaces and beyond. They have been mentoring an entirely new generation of youth, teaching them to embrace, cherish and own their relationship to the ocean and surfing. In combination with activists, scholars, and creatives, they have been rewriting the narrative of surf history and its future evolution, as well as holding us all accountable to take a critical look at the role surf culture has played in perpetuating racism and injustice while challenging the surfing community to take meaningful action. The reality is, that there will always be people across every aspect of society, including surfing, that will choose to remain selfish, lazy, and ignorant, never taking the time or spending the energy to expand their horizons and embrace what it can mean to be fully human and connected to others. But the construct of race, and the systemic implementation of its fear made manifest, racism, is already on notice and has been given its walking papers. It is long overdue and it’s just a matter of time. How long a time depends on how much work is willing to be done on the part of surfers, surf culture and the money and power that drives the surf industry. As I wrote at the bottom of the website, “Together, we decide where we go from here.”

The opening phrase on the project’s website is: “This is a conversation. And now that you’re here, you’re a part of the conversation.” What are some ways in which surfers around the world can initiate conversations?

An easy way to begin the process is to spend some time on the website and check out the resources there. There’s a pretty sizable amount of information a person can access, if they just take the time. It is a great jumping off point to begin to understand the history and context of racism in surfing, with movies, books, magazine articles, as well as audio narratives and other ways to get hip to what’s going on. There are also lots of organizations on the site, and you can contact them to donate money, volunteer time, surf gear, etc. The entire reason I created the website was specifically for the purpose of connecting people to these issues, and to provide opportunities to take action. And from personal experience, all of the resources, people, and organizations I sought out led me to a wider community around the world working to dismantle racism and change surfing for the better.

Aside from that, connect with your fellow surfers to begin to have conversations. You would be surprised how much you will learn about your community and where things are at through having intentional dialogue. Get a bunch of your surf buddies together and watch a film like White Wash, then discuss it. Hell, just do an internet search for “Racism in Surfing”, and dive into that. The information is out there, you just have to be willing to seek it out. And after you feel like you’ve done a little bit of work to understand what’s going on, then ask yourself “What can I do to change it?” and proceed from there. Again, from my personal experience, you might not know where to start; it may feel tricky, you may feel anxious about going there, and you’re not always going to do it right or well. But the important thing is that you make the effort, be willing to learn, grow, and make it a part of how you show up in the world every day. You will find people to help you, guide you and lead you to other allies. The community is out there, and they need you to be part of it!

Have you got a next step planned for the project?

I plan to continue my research and to seek funding so I can expand the project to include indigenous perspectives, as well as critiques around sex, gender, body image, ablism and other areas where surfing often misses opportunities to be inclusive, supportive, and respectful. I am also planning to turn some of the stories from the audio narratives into a live, theater performance. As for the outreach portion of the project, I will be trying to raise money to build the Decolonize The Surf VW van educational experience. I want to bring as many people as possible into this conversation. I created this project, but I don’t view it as really being mine. I view it as a community effort and a place to gather, learn and act collectively. Aside from that, I will always be working to understand and unpack my own blind spots and areas for improvement, while I continue to create work that seeks to dismantle oppression and builds solidarity. As Dr. Cornel West often says, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” And I believe that.

The author and Surf Simply would like to thank David Crellin for his assistance with the article. For more information on the project, visit the Decolonize The Surf website or follow them on Instagram.

decolonizethesurf

**********

Editor’s Note:

Throughout this article we have capitalised all instances of “White” in reference to race, as per the updated Chicago Style Guide and other sources. The capitalisation of Black and White when referring to race is something that is still being discussed in some areas, but our preference is to capitalise both.