Interviews, Surf cultureDaniel Esparza and the History of Surfing in Spain

Many of us who surf the same break regularly know its best wind and swell conditions, where to sit and wait for sets, perhaps that tiny channel which only becomes visible on low tide but is crucial when paddling out on a big day. We know the crew that hangs around the car park, the person who got the biggest barrel last Sunday, the neighbor who repairs boards perfectly. We can maybe even pick out the texture of the sand or the smell of the onshore breeze among all other beaches in the world. And yet, just how well do we really know our local surf spot?

For Spanish surfer-cum-historian Daniel Esparza, digging into his local break’s past led him to study the entire nation’s surf history, which in turn served as a way for him to merge his two passions, nurture his long-distance relationship with the sport and contribute to a deeper understanding of our global surf culture.

Like many, Daniel’s first surf memory is not linked to surfing per se, but music.

“When I was 3 or 4 years old I was impressed by the cover of a Boney M. album, Oceans of Fantasy, where the group members surfed a giant blue wave. I still keep it.”

He only connected with the actual practice of riding waves a decade later, at age 14, when he began bodyboarding on the south coast of Gran Canaria island; at 17 he got sponsored by Rip Curl, taking the first steps into a deeper and more serious relationship with surfing. But that didn’t seem to be his raison d’être.

“If by winning one means winning, I never won anything; it was the trips, the places, and the people that I met that I value the most from those years.”

Fast forward another decade and, aged 28, Daniel decided to move to the heart of the European continent and pursue an academic career, stepping away from the coastal environment long-term for the first time in his life.

“Being far from the sea was key to start another kind of relationship with surfing. As a professor and historian, I became interested in learning about the beginnings of the art of riding waves in my locality, Málaga; then in all of Spain and finally the rest of Europe. After years of research and traveling, I ended up publishing several scientific articles and two books: the History of Surfing in Spain, and the History of Surfing in Malaga. In 2014, I created Olo Surf History, the first surf history website in Spanish – although some entries are in English.”

Surf Simply caught up with Daniel to find out more about the development of surfing in Spain and its role in the dissemination of surfing in Europe and, ultimately, the world.

In 2011, you published your first paper about the beginnings of surfing in Spain, then the aforementioned books and, more recently, a case study on the origins of Spanish surf culture. In your opinion, why is Spanish surf history important for the European and global surf community?

I will tell you two curiosities that hint the importance of the Spanish surf history within the general context of surf history – one on a global level, another specific to Europe.

The first curiosity is related to what is currently the earliest written reference to the art of riding waves, recorded by Spaniard José Acosta, who described the indigenous population of Callao, Lima, in the mid-16th century riding on their Caballitos de Totora.

The second curiosity has to do with the beginnings of surfing in Europe. It is known that Peter Viertel – a Hollywood scriptwriter and husband of actress Deborah Kerr – surfed (or tried to surf) in Biarritz back in 1956 with a board he’d brought from California. Viertel left the board with some locals who, inspired by what they’d seen, created a group of surfers (among them the future board manufacturer Barland) from which a surf culture and industry in this part of Europe sprouted.

But here’s the interesting bit: That surfboard was actually flown into Spain by Dick Zanuck, son of 20th Century Fox mogul, who smuggled it as cargo for the filming of The Sun Also Rises (based on Hemingway’s novel), which was shot in Pamplona (northern Spain) and of which Peter Viertel was the scriptwriter. When Dick’s father found out, he sent his son back to California, leaving Viertel in Pamplona with the board. Since there is no sea in Pamplona, Viertel went to Biarritz to try the board out. It’s worth recalling that, at that time, Spain was under the authoritarian regime of General Franco and the borders were well guarded, which means he must’ve smuggled the board in his van across the Spanish border into France. Anyway, my point is that surfing in France – a country known as the primary precursor in European surf history – really started in Spain, illegally (laughs).

What were your first steps when deciding to work on your first study back in 2011?

The first was the desire to know the beginnings of surfing in my city, Malaga. Back in 2004, there were no traces of it – neither on the internet nor in bookstores – which made me realise that if I wanted to know the past, I would have to investigate it myself. I went to the beach in Malaga, looked for people, interviewed pioneers, took photos, examined letters and telegrams and press clippings. I pulled the thread, so to speak; I travelled through Spain looking for pioneers and talked to them. Then I went to the state public archives and cross-referenced information so as to try to reconstruct the beginnings. Basically, the local took me to the national, the national to the universal.

It must have been very interesting to meet and chat with some of your country’s key surf figures.

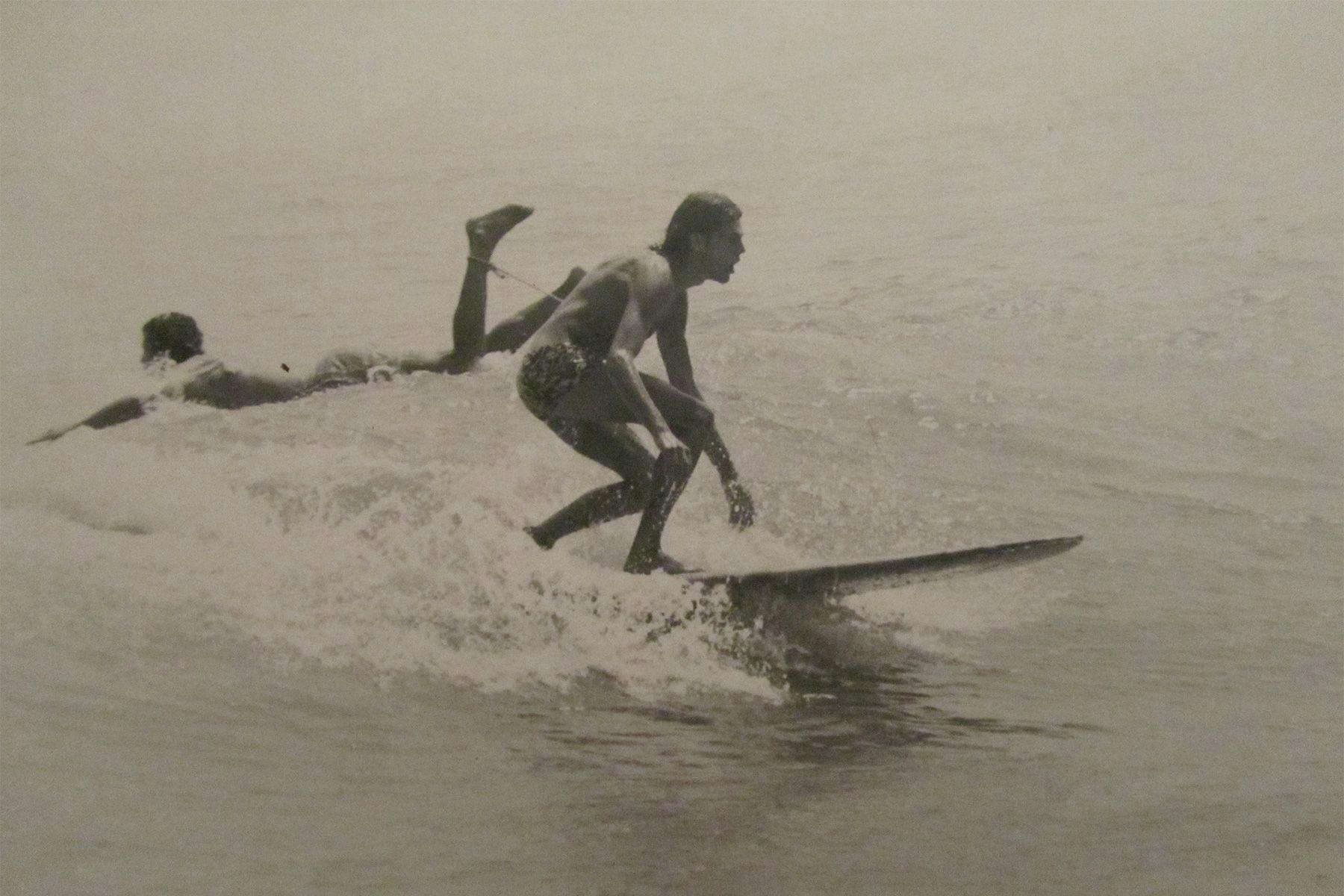

Spending time with them has been the best part of the research. Many opened their houses, their personal archives, and shared their life experiences. We spent hours looking at photos; I listened and travelled back in time to the stories they recounted as if I was living them.

One of your studies that stands out in my opinion was the one published in 2016, Towards a Theory of Surfing Expansion, which revolves around the idea of developing a theoretical framework on the history of surfing expansion using Spain as a case study. How did this concept come about?

After several years of research and comparing the different models of genesis in different nuclei of Spain, Europe and the world, I saw the potential to work on a theory about the diffusion of surfing – so I prepared a 15-page article developing the theory. Those interested can find it in the International Journal of Sports Science.

In this paper, you point out how although Spain was home to the first precursor of surfing in Europe, Ignacio Arana, the practice of wave riding did not gain momentum until almost 5 years later. What were the reasons this first contact did not stick?

Ignacio Arana was the first Spanish consul in Hawaii; he arrived in Honolulu in 1911 and left in 1914. He took two surfboards back to Spain (we do not know what kind, if alaia or paipo) as well as the first surf book in history, published in 1910 in Honolulu, featuring early surf photography. There is no proof that he used those boards in Spain – but he might have. I was able to find out through the Hawaiian press of the time that he was an athlete and organized tennis matches on Wednesdays at Hotel Moana in Honolulu, where he also surfed. There’s a good chance that’s where he met Duke Kahanamoku and got the boards and the surf book. Arana died of Spanish flu in 1918, aged 38, in Newcastle (UK) where he had been appointed as consul. The boards were burned during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) but the book remains with his family until today. Arana was a precursor of surfing in Europe, but now we know he was not the first, for there is evidence that in the UK people surfed years before him.

Surfing did not take place in Spain during the first half of the 20th century because nobody knew it, and those who did know about it did not think it could be practiced in Spain. Surfing in Spain gained momentum from the 60s, through the influence of mass media and foreigner visitors as well as the marines of the US naval base of Rota in southern Spain, some of whom brought along surfboards.

Based on the information you’ve gathered, what were some of the ways in which different European countries influenced one another in the creation/development of a surf culture? How did they relate to Spain?

The UK and France were key players in the evolution of surfing in Spain in the 60s and 70s because that’s where the most developed surf industry was, so many Spanish surfers crossed the border to buy boards. As I mentioned before, another strong influence on the dissemination of surfing in Spain was that of foreigners who passed through and ended up selling their boards.

For Spaniards, the European surf championships of the 60s and 70s – which used to be held in France, the UK and, at times, Ireland – were like going to a congress to see the latest designs. In the absence of the internet, travelling and seeing with one’s own eyes was the best way to learn new techniques, not only in surfing but in how to make boards.

There are beautiful stories to tell, namely that of Pepe Almoguera, the pioneer of surfing in the Spanish Mediterranean, who by the spring of 1972 was the only surfer in Malaga. He had a primitive technique because he had never seen anyone surfing in person, only once at the cinema, which was what inspired him to try it in the first place. One day, Pepe saw a surfer (who he later found out to be from California) riding small waves with an incredible technique right in front of his house. For him it was like seeing an alien! There and then he realized what surfing really was: how to play with the wall of the wave. Pepe did not remember the name of that surfer (maybe Paul?). They got talking and Paul gave him a copy of Surfer magazine, the Olympus of the gods for Pepe, something awful and inaccessible for an adolescent isolated from the world. It would be great to find Paul today (if he was called Paul); he should be around 70-75 years old.

That encounter connected Pepe with the [surf] world and changed the course of the history of surfing in the Spanish Mediterranean, accelerating its development. Pepe then wrote to an American address asking them to send him a book on how to make surfboards. He became an incredible shaper and ended up creating a surfboard brand called Acacias. One of the boards that he shaped for Toño, a surfer from Málaga, was used in Zarautz (Basque Country) circa 1975, catching the attention of Mike Tabeling to the point he wanted to buy it.

What would you say are some peculiarities in Spain’s surf culture?

The surf culture is quite globalized in general, however much dominated by the Anglo-Saxon world. I do not find peculiarities in Spain that make it different from other places in the world, except for the greatness of surfing in the Mediterranean which, due to its inconsistency, is practiced with a lot of passion. In Spain, besides the Atlantic Ocean, a fair share of the coastline is bathed by the calmness of the Mediterranean, which fosters an admirable mentality amongst surfers in the Mediterranean – whether they are from Spain, France, Italy, Croatia, Israel or Egypt – marked by resilience, self-control and patience. I summarize that mentality in the following way: “When there are no waves, tomorrow will be the day; When there are waves, tomorrow is today.”

In your 2016 paper you also mention how “surfing began at almost the same time in several pioneer centers along the Spanish coast” (between 1964 -1968) and yet they did not necessarily know of each other for a few years. When and how did the Spanish surf culture connect and develop a national identity?

There was one person in particular who was key: Nito Biescas Vignau, whom I met during my investigations and now consider a friend. In 1969, Nito organized in Zarautz what is considered to be the first surfing championship in Spain. Dozens of surfers came from the north coast of the Cantabrian Sea. There was great brotherhood; it was a party. The championship received media attention in local and national newspapers and that particular meeting served to organize the first surfing federation in the country. The championship continued for several years. Everyone remembers the huge Hawaiian-themed parties that were held at the end of the championship.

As a surf historian, how do you think researchers and surfers can work together to further study and unveil important events in the global history of surf culture?

The aforementioned 2016 paper, Towards a theory of surfing diffusion, is a starting point to organize and classify the different types of genesis that have occurred in the world. It would be good to join forces, and for other researchers in their local areas of the world present their results and classify them within the model that I have proposed, or another that improves it. It’s about moving forward. In addition to describing results, it is good to be able to explain them within a general theory, in comparative perspective.