Science & SkepticismCalculating the tides: The Rule of Twelfths

Lets begin this piece by asking a question; how often do you consider the tides before going for a surf? Playa Guiones, where the Surf Simply resort is based is lucky to work all the way through from high to low. Where the tide is at any given time though may influence certain decisions before we paddle out; like for example where to surf, or which surfboard to ride. Typically at high tide there would be a slow, fatter wave breaking, and a fast more hollow wave breaking at low tide, with those characteristics transitioning through mid tide. This becomes even more critical when we travel up or down the coast to breaks more drastically affected by tides; like reefs for example.

As surfers we are probably more clued into the movements of the tides than any other group of people, as even the small changes in the tide can affect the way in which the waves will break at any given state. The interesting thing is that whilst we are aware of the changes in the tide, the way we talk about the tide is very basic, which can often lead to being tripped up.

So lets try an idea, and see how it can positively impact our surfing.

Before we go into this in detail, lets review the basic system and terminology. The tides are created by the gravitational affect of our orbit around the sun, and the moons orbit around the earth. As the earth spins every 24 hours, water in the oceans is moved around by the gravitational pull and thus creating the tides.

Lets debunk a little myth. The reason the moon and sun have an affect on the ocean is due to the oceans massive size; the same gravitational pull from the moon does not affect any internal parts of our body. When you are sat at your desk, there is a greater gravitational pull from your PC mouse, than there is from the moon – because of the relative size, and distance to the mouse. So if you hear someone express that their behaviour is affected by the moon just nod, smile and immediately dismiss it as pseudo science.

So back to business; most places around the world will see two high tides per day, and two low tides per day; with approximately 6 hours of separation between each. There are some places that only get one cycle every 24 hours and there are a few very unusual places where the tidal pattern is both unique and irregular. Having said that, working out the times of high and low tide on any given day is actually fairly easy, as its linked to the orbit of the moon; so once you have an understanding of the flow of the tide at any given location you can then make very accurate predictions far out into the future.

The next thing to consider, as well as the time, is how much the tide goes up and down, which is a little bit more complicated as it depends on where the sun and moon are relative to each other and to our location. So when all three of the bodies line up we get a full moon or a new moon, and the range between high and low tide is very large – known typically as a spring or king tide. When the sun and the moon are at 90 degrees to the earth, we would see a half moon in the sky, and get neap tides – where the range in height is much smaller – that process runs on an approximate 4 week cycle of spring/neap/spring/neap as the moon orbits the earth each month.

Now just to complicate things further, another variable has to be considered. The fact that the earth has an elliptical orbit around the sun and, how far we are from the sun will contribute to the size of the tide. Thats why at certain times of the year the tides are larger than others.

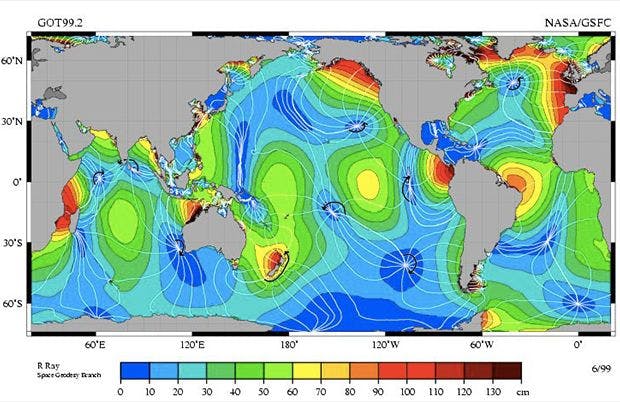

The final piece of the puzzle, is that as the earth spins, all these massive movements of water are pulled into rotation around Amphidromic Points in the middle of the oceans. The further you are from these points, the bigger the range in height from high to low tide – that’s why in the north Atlantic there are huge tidal swings around Europe and on the east coast of the US; where as over in Hawaii there is barely a foot in tidal difference.

Amphidromic Points are the dark blue areas on the map below, where the white cotidal lines come together. (Cotidal lines are connecting points at which a tidal level, especially high tide, occurs simultaneously).

So how does all this affect us as surfers? Well like mentioned above, different reefs and beach breaks work at different states of the tide, and so turning up at the wrong time of day may leave you with a disappointing set of conditions. If you ask most surfers what is the ideal tide for spot x, most will reply with something simple like ‘high tide’, ‘low tide’ or ‘mid tide’; but with all the variations highlighted above, those term don’t really cut it anymore.

For example lets consider a reef, and in order to break properly it needs a certain amount of water over it, and the general consensus is that the reef works best at low tide. Now on some spring tides the tide may drop so much that the reef is dangerously shallow, but on some neap tides the water may not even go out enough to make a wave. In other words we should be thinking about the tide as an absolute height, rather than in high or low – as there is so much variation between high and low throughout the year.

Those occasions when you turn up to the beach and the conditions aren’t ideal, we often put it down then the direction of the swell, or the wind, and obviously they may be a contributing factor but at the same time if we are more accurate when considering the tide, we might manage to score a little more often, or at the very least avoid a goose chase after waves that never seem to work.

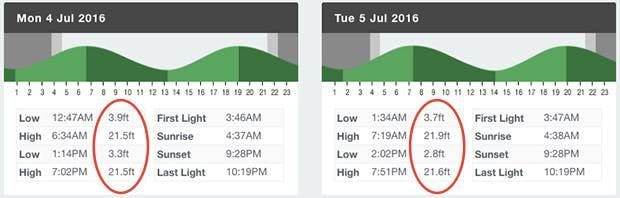

In certain worlds, getting the variations in the tide wrong can be very expensive; yachting for example. It is rumoured that there are two types of sailors – those who have run a boat aground, and those who are liars. Consequently in the boating world there are some useful ways to at least guess the height of the tide at any given time. To start with, when you are reviewing your local tide table for the times of high and low tide, the neighbouring column is the height of the tide, (unless of course you are in France, where another system is in place called the coefficient; more like a percentage of the tide height, where a spring high would be 100%, and a spring low would be 0%).

The height of the tide is measured from an imaginary point known as chart datum. Chart datum is where all the heights and depths are taken from a nautical chart. So if you review the tide table and the chart, you can then use the relevant data to show how much water will be over a group of rocks at high tide for example, or how far up or down the beach the water will come each day. You will end up with a number in feet which is relative to chart datum.

Using the high and low tide data, we can easily work out how much water will be over a certain point at high and low tide. During the rest of the day however, it is a little more difficult. Many assume the tide flows from high to low at the same speed, and then low to high at the same speed throughout; however this is not the case. Luckily though, the tides move in quite a predictable way, and although it is not a constant flow, there is a predictable variation in that flow.

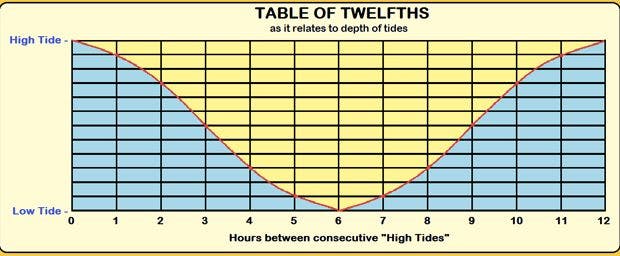

Imagining the tidal flow in graph form, it could be illustrated as a bell curve; in fact the speed of the tide is similar to that of a swinging pendulum; in the sense that as the pendulum swings towards the top it slows until it comes to a stop (this would be high tide), then as it drops it also accelerates towards the centre where the pendulum is moving at its fastest (mid tide), then once again it reaches the opposite top and slows to a stop (low tide) before reversing the process.

There are many techniques for predicting the tide, and potentially this method should be avoided if you were navigating an oil baron’s super yacht through the shallow waters off the Caribbean. But, if you’re a surfer who is interested in getting more from each session, then this is the system for you; The Rule of Twelfths. An efficient way of guesstimating how much water there is, at any given time of day, over a particular point.

The rule of twelfths works like this; take the difference in height between the high and low tide on that day, and divide that by 12 equal chunks. For example, if high tide was 8ft above chart datum, and low is 2ft above chart datum – there is a 6ft difference, divided that into 12 even chunks; equaling 0.5ft per chunk. Simple.

What we then do is assume that there is a 6 hour gap between high and low tide; although not completely accurate, it is close enough for what we are attempting here.

For each hour of those 6, the tide will move at a fixed rate.

So starting at low tide:

The first hour, 1 twelfth of the tide would rise; so one chunk would come in, 0.5 ft.

The second hour, 2 twelfths of the total will come in, therefore 1 ft.

The third hour, the tide is starting to move quickly, and so 3 twelfths will come on, therefore 1.5ft.

At this point we are now passing mid tide.

The fourth hour again is 3 twelfths, so another 1.5ft.

The fifth hour the tide slows down again, 2 twelfths, therefore 1ft.

The sixth and final hour, 1 twelfth would come in, and therefore 0.5ft.

The tide would then drop following the same pattern. This is a way of putting a numerical value on the interim period between high and low tide, where the tide is running particularly fast.

So how would this look? Well we now know that those first two hours from high tide or low tide you will only see 2 twelfths of the total water come in or drop; probably unnoticeable, even in a place of big tidal ranges. However, during those middle two hours, half of the total volume of water will move in or out, 6 twelfths in one direction – a significant change in only 2 hours.

What can you do with this? If you go to the beach, and the tide on that day is making the conditions particularly good or bad, take a note of what time it is, and then at home you can use the rule of twelfths to work out exactly what the tide height was at that point and use the information to plan a future surf; and build a much more detailed picture of a spot.

Lets use a real example of this, from a local reef near to us here at the Surf Simply Resort, Costa Rica:

We paddle out at high tide, and after a 2 hour surf the tide became too low to surf and exposed rocks. This made the break too dangerous to continue.

High tide that day was 8.8ft above chart datum, and low tide was 1.2ft so the total tidal range was 7.6ft; divided into twelfths that makes 7.5 inches per 1 twelfth.

Using the rule of twelfths we calculated that after our initial 2 hour surf, 3 twelfths of the total, or just under 2 ft of water would have gone out – leaving approximately 7ft of water over the reef.

So, rather than saying the reef works at high tide and doesn’t work at low tide, we actually know that the reef works whenever there is more than approximately 7ft of water over it – this is important because on a big spring tide, we can get as much as 11ft above chart datum and so this break can work for much longer on a dropping spring tide. Where as on a neap tide we may only get a total of 7ft over the reef, and so there might not be a window to surf it at all.

So, in conclusion, whenever a big swell comes in, you can now build more data into your surfs, and have more reliable information to make decisions from. Some tide watches now offer something similar, an algorithm using data from forecasting sites like Surfline – they do however come with a hefty price tag. So understanding and using the rue of twelfths is not only an interesting exercise, but also a cost effective one.