Experiences, TravelBackstage on an Ocean Crossing

Behind The Scenes With Two Surfers Across The Pacific

There is a romanticism about voyaging which I believe derives more from the deprivation of land than the undertaking of a sea journey. Inconspicuously, it also has to do with the irony that, despite coming from water, we can’t breathe under it. So on the night prior to setting sail across the Pacific Ocean, I didn’t prepare – I romanticised. I dove into the depths of imagination, picking bits and pieces of films watched, pictures seen, tales heard, and my own experience growing up by the ocean. These bleary excerpts soon compiled into sharp scenes of what my first crossing may be like – or rather how I’d like it to be: sunny afternoons laying comfortably on the deck, arms crossed behind my head, looking up at the passing clouds while my mind drifted in the rhythm of the wake, a gentle smile on my face. I foresaw all the books I was going to read, the questions I would finally find answers to. A sense of tranquillity accompanied those reveries. I clung to it just as any foolhardy, lucid dreamer would.

The initial days spent sailing along the docile Caribbean waters of Panama – from Bocas del Toro down to Escudo de Veraguas and Isla Grande, until reaching Colón – fit right into my utopian preconception. Gentle breezes filled the main sail, pushing us on a cradle-like motion that sent the boat forward without compelling us to hold on. The daytime backdrop resembled the kind of romantic painting someone who’d never been at sea but daydreamed of seafaring would portray. At night, both sky and sea bore the same hypnotising dark-blue hue, almost undistinguishable towards the horizon. And so the setting remained, until the opening gates and gushing waters of the Panama Canal lowered us into the high-tides and murky-green of the Pacific.

On the very first leg of our Pacific sail, from Panama City to Playa Venao, a solid 50knot locomotive of air blew away my romanticism, making the boat heel-over. With the wind also came the reality that, despite what the unseasoned sailor inside me might have reckoned, a mono-hull yacht tilts when underway. The deck now formed an obtuse angle with the water, 120-140 degrees, and the vessel bounced against white horses. There I stood on the boat’s rail, my back against the floor of the cockpit, feet close enough to the water’s surface to feel its temperature, hands firmly grasping a rope that seemed to dictate whether or not the boat would capsize. My friend, captain, and only other crew, Josh, shouted vainly against the wind’s much higher pitch; unable to make out full sentences, I relied on his facial expressions and lose words to decide if I should pull or give rope. The creaking of the hinge, the flapping of the canvas, the rattle of things falling down in the cabin, ropes swinging willy-nilly, the dull noise coming from the hull when meeting the next wave as if the boat was being strangled. An earthquake on water. We were literally unstoppable.

That afternoon, when we dropped anchor at a sheltered bay and the wind subdued, every last drop of my previous romanticism evaporated. With a warm cup of tea in hand, I could no longer envisage those calm, sunny afternoons gliding smoothly. Third-person flashbacks of the last hour flicked in my mind’s eye: I could see my own eyes pop, I could count my heartbeats. This first Pacific leg was inversely proportional to the entire experience along the Caribbean coast. It couldn’t be pigeonholed as dread, though; more like the disappointing startle when unwrapping a present you didn’t ask for. I wondered if, like the story behind the naming of Greenland and Iceland, early map-makers had hoped to deceive people into believing that this ocean was “pacific.” At any rate, the other extreme of sailing had just presented itself, and if that was what the next few thousand miles until French Polynesia would be like, then I’d better listen to Josh and wear a life jacket.

Fortunately, those 50 knot winds off the coast of Panama were as radical of a ride as we had in the entire trip to Polynesia. “We go South until we find the trade winds,” Josh told me, dragging his finger over the paper chart as we motored away from Panama towards the Galapagos. Later that night, while sitting on the cockpit settling into night watch, I caught myself mulling over the almost two years I had spent in Central America and realised that, up until then, I had only crossed oceans by air – a fast-paced experience that never allowed me to grasp the minutiae of the transition. But this was different. As Kuhela drifted away from the coast, I had the opportunity to digest what had passed: the unhealthy relationship I had left behind, my longing to partake more often in my sibling’s lives, the frustration of still struggling to find a so-called ‘calling’ or ‘purpose’ – stuff that, when placed next to the trip I was about to undertake, made the act of sailing across an ocean seem mundane, secondary. With each nautical mile the GPS counted, the physical distance shook emotional proximities, as if separating two magnets, slowly.

It took us eight days to cross from Boca Chica, Panama to San Cristobal Island, Galapagos, most of which were framed by intense sunshine, wind speeds that barely reached whole decimal figures, and uncomfortably warm temperatures caused by the lack of wind. A week under such conditions was enough time to catch a glimpse of yet another side of the life at sea, as well as the nuances of long-distance sailing. I began noticing, for instance, how the wind itself or the lack thereof wasn’t a nuisance – the metallic groan of the boom swinging as a result of unfilled sails was. It also dawned on me how well the sun tells the time; how hard it was to steer in a straight line; how scary it can be not knowing where a noise is coming from. Those were details the brushes of that same landlocked, starry-eyed painter wouldn’t have been able to translate. They were concerns or struggles that had little to do with the natural elements – things I couldn’t control – and more to do with my internal nature. They were the results of my perceptions adjusting to a newfound reality.

The incessant swing of the boat dictated the way in which everything happened and whenever I forgot to keep my hands prompt, a bump and subsequent bruise reminded me that I was on a 38ft yacht. As much as twelve metres by three metres of external area (I’m not sure of the size of the internal cabin) didn’t seem like much, physically, for me to feel free to move. Indeed, a space-related anxiety would hit me every now and again, but its roots sprang from the fact that I couldn’t leave even if I wanted, not so much for being enclosed in a small space. It was an ilk of claustrophobia related to its consequences, not its causes. Accordingly, my body began to reconstruct its kinaesthesia, prioritizing sharper turns and shorter steps over its usual earth-borne motility. I responded, rather than act. Moving wasn’t something I did, it was something that happened to me. There was a kind of double-gravity at work – a sideways force pulled and pushed me around according to how the hull touched the water’s surface.

The small space had its plus points – it was cosy. This unthreatening cosiness reflected the vessel’s interior design and the way in which couches, tables, cupboards and cup holders were arranged: carefully, harmoniously, just the right amount. Impeccable transitions that leave no space to waste. Equally remarkable was the thoughtful function of furniture: the oven balanced on a steel bar, swinging freely and remaining horizontal as the boat rocked, while the stove tops featured adjustable metal claws to hold pots and kettle in place. My bed – aka the cave – was a narrow, tunnel-like compartment on the starboard side of the boat’s rear that only allowed me to lay down. To get up, I had to slide my hips down to where my feet were, much like a worm would, otherwise my head would pay the price.

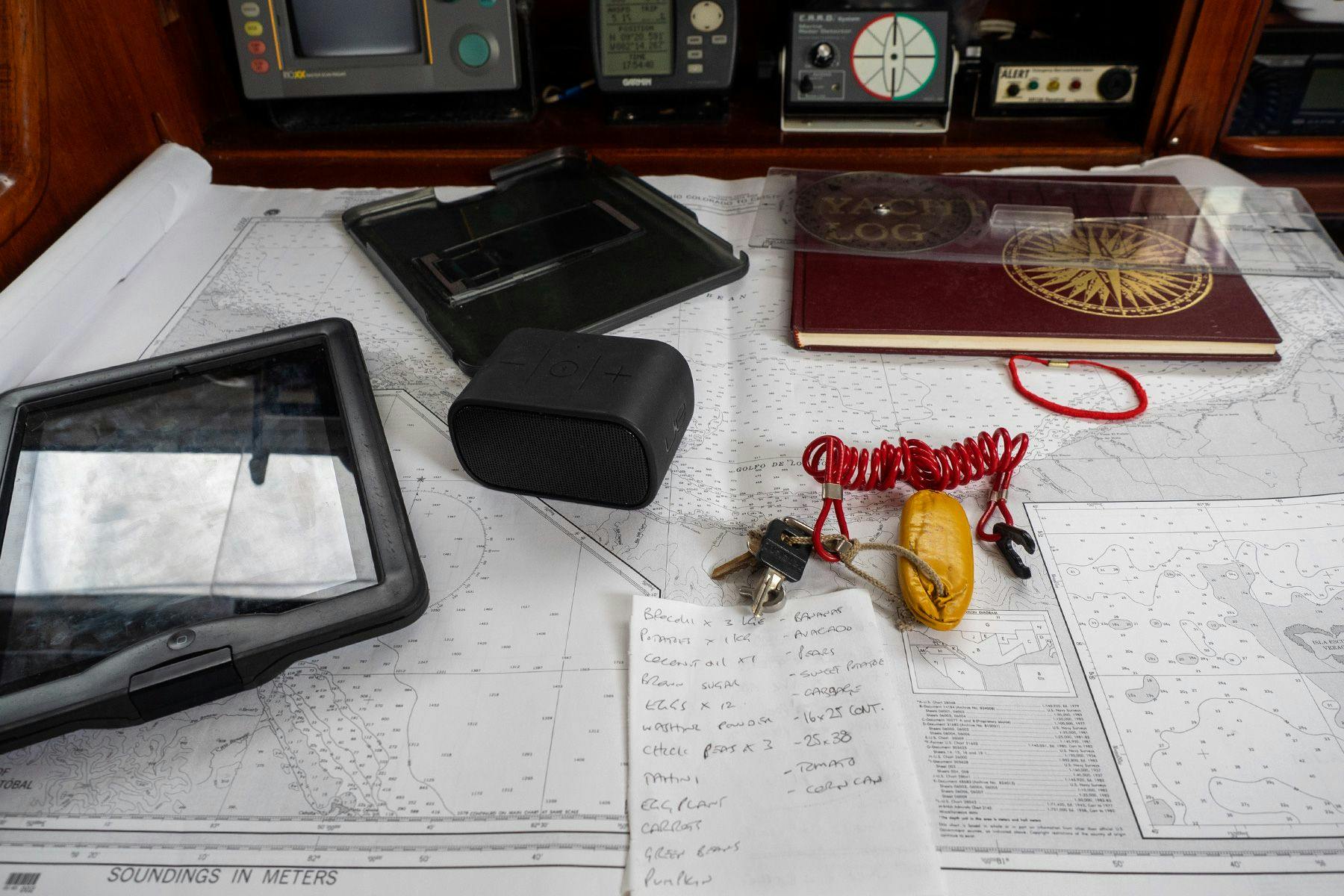

This simplicity and functionality stretched beyond the realms of design, however. It resonated with me as a representation of values through the conscious shaping of a way of life: a life of owning what you need, and knowing what you own; a life where there is little space for frivolities and where your energy can be directed to trimming the sails, so to speak. The only things that it felt good to have a surplus of were spare parts. Nonetheless, we double-questioned our necessities and everything deemed useful was zip-locked (gotta keep the humidity out), labelled, and placed in its designated cupboard or shelf. By the second time I used the canned tuna I knew they neighboured the canned beans. There was a type of rag for every “type” of cleaning. At first I found this methodic arrangement somewhat fastidious, but then realised you’d want to know where the n12 screwdriver is when a strong gust snaps a cable. Or, where the chocolate bar has been stashed when it’s tea o’clock.

The refreshing sensation that comes after a shower was as limited as our water reserves. The water-maker only purified 5 litres of saltwater per hour, and considering that the priority was to keep hydrated, we washed the dishes and brushed our teeth with seawater, seldom showering with potable water; and when that did happen, frugality was off-the-essence. Saltwater showers meant bucketing seawater and dumping it overhead; the fresh-water wash-up procedure consisted of pumping one of those garden pressure sprayer bottles and using hand-held shower head to gauge outflow.

By the time we set sail from the Galapagos, I had already been living onboard for over three months and was thus familiar with the Kuhela’s personality, topography and motion – both anchored and underway. I knew when to duck my head not to hit the main hatch, which fender to tie where and how many pumps were required to flush the toilet properly. At the beginning, I was a child on the first days of kindergarten, but once we pulled up anchor, set the course to Polynesia and accepted we would be adrift for at least three weeks, I felt like puberty had arrived.

Josh and I met roughly a year prior to setting sail across the Pacific; we stumbled into each other while surfing the point at Careneros, in Bocas del Toro, Panama. An honest, determined guy, passionate about all-things-water, Josh had just purchased Kuhela in Florida and sailed down the Caribbean to Panama. I had been living in Bocas for a some months, wondering where all those sailboats came from. Although surfing was what connected us, it was the inner wish to find hidden surf spots over which we truly bonded. Beyond surfing, we were both interested in stationary and writing, carpentry, cooking, and meditation. We chatted about past relationships with the same frequency that we discussed which fin setup worked best. He showed me how to be determined, I showed him how to bake bread. But more than anything, we both strove for simplicity in all aspects of life. Following our meeting, he flew back to Australia for work and I carried on my Central America trip. We barely spoke for a year. Then, I got an email from him and, a couple of days later, in a broken Skype call, managed to make up the words “sail”, “Pacific ocean”, “New Zealand”, “need crew”, “want to come with?” Three weeks later I was back in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Another month working on the boat and we cast off.

Since this was also his first ocean crossing, neither of us understood just how much patience and empathy would be required. We were friends but it was a fresh friendship. Our lives were very different in many ways. But even though we barely knew each other, we trusted each other – which seemed capital when picking who you’ll cross an ocean with. Another thing I hadn’t foreseen was the fact that, once out at sea, he was first my captain, then my friend. The choices he made dictated what would happen to both of us, thus by agreeing to join him on this journey, I had agreed to trust his judgement and respect his decisions.

For the first few days after leaving the Galapagos my journal entries talked about weather conditions, sail patterns, sunsets, how fast our stock of fresh veggies was going and the remarkable breakfast of muesli and yogurt we still had. My written voice was excited. Soon the words embodied a less sheepish tone and began describing the automatic pilot that broke down, the routine that began to settle. A week into the trip and mood swings became a constant. From my notes, I savvied that the lack of sleep, the incessant rocking of the boat, and the daily tasks which I saw no sense in doing were getting the best of me. Many external factors, as well as my own personality, influenced this psycho-physical disequilibrium, but the one that took center stage was sleep – or lack thereof. For twenty four nights I didn’t get a full night’s sleep. Neither of us did.

At first we decided to have 2-hour shifts, from 8pm until 8am. But as soon we witnessed the framework to be unsustainable (it took about 30min to brief the other and get ready to bed, plus another 15min to actually fall asleep, and an additional 15min to get ready for the next shift, and that was when no squalls passed through, which required both of us to be on deck), we began 3-hour shifts. The difference was substantial, so we stuck to that setting. Nonetheless, our sleep wasn’t fluid; we barely managed to reach the stage of deep sleep and if we did, it lasted only a little while before the alarm clock rang or the flapping of the sails woke us up. Sleeping became a daydreaming with eyes closed, a blackout that lasted longer than usual.

This inconsistency led to a myriad of naps: the couch, a pillow by the cockpit under the shade after lunchtime…even sitting up my eyes attempted to close more than once. It was clear that the chaotic sleeping pattern disrupted all of my bodily and mental functions, but at that point there was nothing I could do about it apart from snoozing as much as possible and remaining aware of the fact that both my perceptions and temperament shifted whether I liked it or not, so I needed to watch out for how I externalised this imbalance.

Halfway between the Galapagos and the Gambier Islands, French Polynesia, a sense of irony hit me when I realised that, while drifting somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, where water covered all corners of the horizon, thoughts of land could squeeze into my head. Suddenly I was thirsty, but not the kind that any liquid could quench. I thirsted for solid ground. I thought of what it would be like to inebriate myself with dirt, step onto an unmoving surface for a change. Stillness had become a rare commodity: the sense of regaining control over my daily choices; of being able to change environments when I wanted or needed; of feeling the subtle warmth that is constantly released from the Earth; of standing still. As the hull of Kuhela crashed against the waves, sending us up and down in ballet-like thrusts, I thought about land and the things that sprouted out of it, the stuff I didn’t appreciate until I was deprived of it.

With nowhere to run and having not much else to do but think, questions over my attitude began to haunt me. On one side, I had all these internal conflicts – of present, past and future – bubbling inside of me. Memories of land, doubts over my decision to be at sea, anxieties about what was yet to come. On the other hand, there was the fact of being there – and not being alone. Whatever I did or didn’t project had a direct impact on the person with whom I shared those few square metres of floating fibreglass. A thought, a sigh, a scream or a moment of silence took a lot longer to dissipate. They tumbled in the cabin for a while, then moved up to the deck, wrapped around the boom, almost hesitantly exiting the boat. Being a reserved person who communicates poorly, I struggled to filter this avalanche of emotions and thought and physical exhaustion, and to share it with Josh earnestly.

Then we had our first and only actual argument Josh had asked me to keep the speed at 4.5knots, but I was both too tired to pay attention and too unaware of our whereabouts to care about speed. He saw my disregard and fairly enacted his authority as captain and boat owner. In response, I argued that, since we were in the middle of the ocean, at least two weeks away from our destination, whether we were making 4.5 or 4.0 knots wouldn’t make a significant difference in our final goal – arriving. We both spoke our minds and, in the end, realised that it wasn’t a matter of speed or authority, but venting whatever anguish we had been accumulating. We were in this together.

With time, my attitude towards our routine matured, as though I had accepted that now, in the middle of the ocean, there was no alternative but to embrace it all. Or perhaps my actions dissolved into an evermore linear routine. Like the painting of an artist who has never been at sea, no external or internal references assured me that the world was still spinning – or that we were actually moving. Therefore by writing on the log book every couple of hours, noting the days and weather conditions, latitudes and longitudes, time was now linked to distance. We assumed we had X nautical miles to go, but this could mean a week – or two. It was up to the wind. In moments of second-guessing, of existential questions and physical fatigue, just as much as when entranced by starry skies or the candid breeze, I clung to the reality of those numbers counting down and the knowledge that, even if they were wrong, at some point we were bound to hit land.