TravelAl-Jazira Al-Arabiya

“This cruel land can cast a spell which no temperate clime can match”

Wilfred Thesiger

I hadn’t expected to be staying in a fancy hotel on this trip. And it appears to be very nice now that they’ve finished building it. But, when we visited, it wasn’t yet a hotel – just a dream made up of some breezeblock walls on the point. A local entrepreneur is now tempting windsurfers, kite surfers and even the odd regular surfer down here during the summer monsoon (the khareef), to enjoy the right-hand point break out front and the breezy conditions, but back then work had ground to a halt.

My friends Scott and Dan used to run the occasional guided surfaris down the Arabian Peninsula from their base in Dubai at this time of year, but being that this was a trip amongst friends and a tactical strike to meet a swell, we left the big safari tent behind and decided to go a bit feral. Hence bedding down in a building site. Hey, nothing blocks wind like a brick wall.

This trip had been floating around on my to-do list for about four years since seeing a tiny photo of what looked like a point break in a travel magazine in a dentist’s waiting room. E-mails from long-term ex-pat friends who live in the region compounded this curiosity, until photos of the waves and attached eight meter swell forecast charts from Tropical Cyclone Phet earlier in the year landed in my inbox and tipped me over the edge. A juggled flight itinerary for an already-booked trip and an extended stop-over in Dubai were all it took.

We watched the charts as a fresh swell developed and timed our trip to get optimum swell and avoid the strong winds that can so easily destroy these missions. You can’t really spend time down on the edge of the desert waiting days for a weather system to pass when you have to be totally self sufficient in heat that can hover around 40 degrees centigrade. It’s a sparsely populated and inhospitable coastline, there’s not a lot of room for messing around.

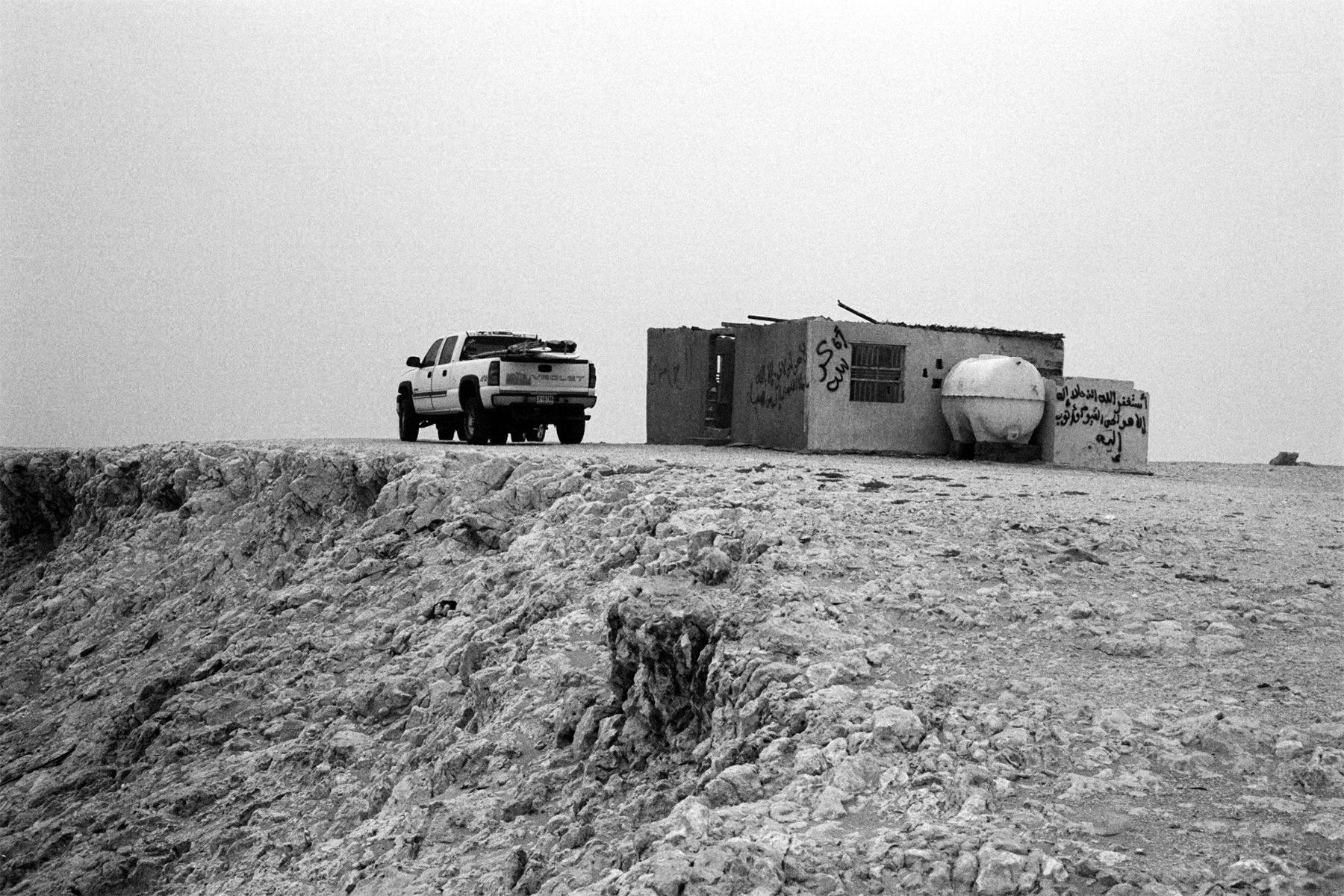

We loaded up the truck with water, tins of food and a ridiculously large array of surfboards and pointed south across the desert. It’s a long way: across craggy mountains then rolling desert carpeted in salt scrub grazed by wild camels. We hit the coast and turned southwest to follow it along the coast of the Indian Ocean. The small fishing settlements were mostly deserted where the fishermen head inland during the monsoon season to work on date farms, and this ghost town feeling coupled with the destruction wrought by Cyclone Phet a month or so previous made it feel like we were in the middle of a news report. Goats browsed the doorways and every now and then local Bedu kids would emerge to wave, or we’d pass a coffee shop and receive a nod from the group of men seated outside. We drove past endless beachies, pausing to check the odd rip bank, but we were really aiming for the point breaks that interrupt the straight line of sand where the desert flows into the sea. A new road has been pushed through the talcum powder like sands of the desert, and we were navigating on GPS co-ordinates to find these precious kinks. Using a map in a featureless expanse of shifting desert is difficult; there are some times when modern technology comes into its own no matter how self sufficient you want to be.

First hour of the first surf: Dan dislocates his shoulder, which serves as the catalyst for one of the more interesting encounters of our trip, a visit to the local ice factory to get ice to press onto his shoulder and abate the pain. The local fishermen who patronize the ice factory gave us typically Bedu directions:

“Deflate your tyres some and drive along the beach for maybe six kilometres, then at the second mountain turn right. Where the three scrub covered big dunes are turn left and it’s two kilometres on from there”

“Can we get there along the road?”

“Yes, go back to the main road, it’s seven kilometres south, first left after the petrol station”

There’s no easy way to describe a dilapidated ice factory out of season in the middle of a desert. Probably safe to say that we provided a point of interest in the workers day turning up to buy the smallest quantity of crushed ice that they would sell us, which turned out to be a 25kg sack.

The surf that we got on this trip was fun. Easy right hand point breaks with open walls to carve and shapely little beach breaks. We didn’t score the sort of waves that will put this area on the front cover of any mainstream surf media any time soon or flood the area with pro photo trips. Perhaps that’s why so few surfers who visit. It’s just not bang for your buck in your two weeks of holiday leave – but that was part of the appeal; being half an ocean away from the next person sat waiting for a wave. On its day the potential for incredible waves is sorely obvious, but the amount of sand that migrates along this stretch means that nothing is ever certain. Enormous beginners luck or the logging of numerous exploratory trips is what is required to cash in around here. Even with the local knowledge present in our truck, it was all still an expedition, a roll of the dice. On one particular point that we surfed one afternoon, the sand had filled in all of the crevices in the rock since the last known visit by friends of friends. What had apparently been a rippable long ride two weeks before was now a series of thick bowly sections. If you could even get one; the sweep running down the point was one of the strongest that I’ve ever tried to paddle against – within three duck-dives we were all a few hundred metres back down towards the beach from the top of the point. On the trip that we’d been hearing stories from two weeks prior, there had apparently been barely any sweep at all and the crew had been relaxing around the take off zone, exchanging fun waves and running laps back up the point.

The huge range of surfboards that were sticking over the tailgate of the truck came in mighty handy. As the tide pushed in the waves started to break wide on many of the points as a result of the sand piled into them by Cyclone Phet, and shortboards were quickly swapped for longer, cruisier craft. A few days after dislocating his shoulder, sitting on the beach became too much and Dan swam out with a set of fins then went back in to return with a yellowed old single fin, only to gain a newfound respect for Bethany Hamilton after gritting his teeth to push himself up using only one arm.

The sense of adventure and of being on a proper expedition is what trips like this are all about. We scored waves, which had been the main focus, but there was a whole lot more to it than that. Most surfers who travel to surf will have inadvertently absorbed some form of surf media relating to their destination prior to arrival: we all know what Jeffreys Bay or G-Land look like, we’re aware of various cultures in surfing locales around the world. The nice thing about going somewhere off the surf radar is that there is no solid benchmark; it’s all so fresh and new. The reception that we received everywhere we went was astounding, and the spirit of hospitality that is so central to these Arabic and Muslim cultures was refreshing for a westerner, particularly in light of how these cultures are often portrayed by some media channels.

By way of example, one afternoon we all strolled down to the beach where skiffs negotiate the shifting peaks to land the catches from the larger dhow fishing boats just offshore, with the dual intentions of buying a fish for dinner and checking the surf on the beachie. Scott started conversing in a mix of Arabic and loose English with the guy who appeared to be the skipper, whilst the other fishermen unloaded the contents of the skiff into the back of a waiting Landcruiser. The skiff was jammed full of tuna and other large fish, plus a massive Marlin and a few decent sized sharks. The dhows that had hauled in this catch were fishing just off the beach, in plain view of where we were surfing. The winds blow the desert sand into the line-up making the water murky and it’s surprisingly chilly for being so far north in the Indian Ocean, and now we knew that there were definitely sharks swimming around.

Scott entered into the customary haggling over price with the skipper, and managed to work him down to what we knew was market price. When the deal was done Scott went to pull out some notes when the skipper shook his head.

“Hura” he said to us: “Free”.

It was all just a game; despite the fact that these guys were subsistence fishermen and it had been a tough few years for them (“next year we hope for more fish, insha’Allah”) they gave us a fish that they could have sold at market, when we could clearly afford it and intended to buy it. We encountered so many instances of generosity and a lot of good-natured curiosity. Everybody wanted to know what five guys from five different countries with a truck load of funny looking luggage were doing camping out in a building site and swimming in the waves, so we received multiple callers at our camp, all of whom just turned up to talk with us, ask us polite questions and share coffee and dates.

On our way back to our construction site camp after a surf one afternoon we were pulled over by a truck load of Arab men as we passed through one of the coastal settlements. The driver, Mahtmoud, recognised Scott and insisted that we join them for coffee. It seemed as though half the men in town turned out to join us as we exchanged stories and “the news” with the locals over cardamom coffee.

After a few days the wind started to pick up again, blowing out the surf and filling the air with sand. We’d paddled hard and run out of coffee. It was time to return to base.

Success really depends upon how you define it. A surf trip’s success might hang on whether you get overhead barrels everyday, whether the photographer gets the shot, and whether or not you drink the beer fridge on the boat dry. It might however be defined however by simply getting rideable waves and putting in a few turns, gathering a bit more information on a piece of under-surfed coast, feeling like you’re a long way from normality and feeling the smiles and hospitality of the local people. We had a successful trip on those terms.

There’s over 900 miles of open, regularly surfable coastline along the Arabian Peninsula, many islands of varying size and accessibility and even more coastline with surfing potential when big swells wrap or come from anywhere other than the prevailing direction*.

That was all I could really think about as the truck hammered back through the desert on our way home, following the line of telegraph poles emerging through the dust haze alongside the tarmac. A land of largely undiscovered wave riding potential; Surfing’s own Empty Quarter where the odd lucky explorer might just strike gold if they’re bold enough to go looking:

“To return to the Empty Quarter would be to answer a challenge, and to remain there for long would be to test myself to the limit. Much of it was unexplored. It was one of the very few places left where I could satisfy an urge to go where others had not been.”

Wilfred Thesiger

Arabian Sands, 1959

The author would like to thank Scott and Dan of Surfing Dubai and Surf House Dubai. If you’re travelling to or have a flight with a layover in Dubai then don’t hesitate to get in touch or pay them a visit for all things surf and SUP in Dubai and the surrounding area.

The effects of plastic pollution in the Indian Ocean on this remote and sparsely populated coastline is clearly visible in many of these images. Please use this as a reminder to consider your use of single use plastics, wherever you live in the world.